De periode van Arabische heerschappij in Georgië, plaatselijk bekend als "Araboba", strekte zich uit van de eerste Arabische invallen rond het midden van de 7e eeuw tot de uiteindelijke nederlaag van het emiraat Tbilisi door koning David IV in 1122. In tegenstelling tot andere regio's die getroffen werden door islamitische veroveringen bleven de culturele en politieke structuren van Georgië relatief intact.De Georgische bevolking behield grotendeels haar

christelijk geloof , en de adel behield de controle over hun leengoederen, terwijl de Arabische heersers zich voornamelijk concentreerden op het verkrijgen van eerbetoon, dat ze vaak moeilijk konden afdwingen.De regio ondervond echter aanzienlijke verwoestingen als gevolg van herhaalde militaire campagnes, en de kaliefen behielden gedurende een groot deel van dit tijdperk hun invloed op de interne dynamiek van Georgië.De geschiedenis van de Arabische overheersing in Georgië is doorgaans verdeeld in drie hoofdperioden:1.

Vroege Arabische verovering (645-736) : Deze periode begon met de eerste verschijning van Arabische legers rond 645, onder het

Umayyad-kalifaat , en eindigde met de oprichting van het emiraat Tbilisi in 736. Het werd gekenmerkt door de progressieve bewering van politieke controle over Georgische landen.2.

Emiraat Tbilisi (736-853) : Gedurende deze tijd oefende het emiraat Tbilisi controle uit over heel Oost-Georgië.Deze fase eindigde toen het

Abbasidische kalifaat Tbilisi in 853 verwoestte om een opstand van de plaatselijke emir te onderdrukken, wat het einde betekende van de wijdverbreide Arabische overheersing in de regio.3.

Daling van de Arabische overheersing (853-1122) : Na de verwoesting van Tbilisi begon de macht van het emiraat af te nemen en verloor geleidelijk terrein aan opkomende onafhankelijke Georgische staten.Het Grote

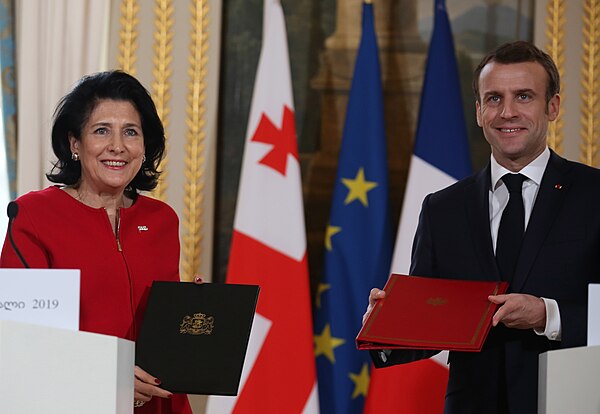

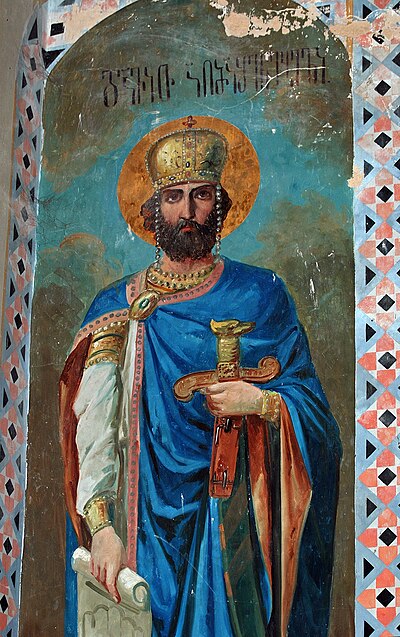

Seltsjoekenrijk verving uiteindelijk de Arabieren als de dominante kracht in het Midden-Oosten in de tweede helft van de 11e eeuw.Desondanks bleef Tbilisi onder Arabische heerschappij tot de bevrijding door koning David IV in 1122.

Vroege Arabische veroveringen (645-736)In het begin van de 7e eeuw navigeerde het Principaat van Iberia, dat het grootste deel van het huidige Georgië besloeg, bedreven door het complexe politieke landschap dat werd gedomineerd door het Byzantijnse en Sassanidische rijk.Door waar nodig van loyaliteit te wisselen, slaagde Iberia erin een zekere mate van onafhankelijkheid te behouden.Dit delicate evenwicht veranderde in 626 toen

de Byzantijnse keizer Heraclius Tbilisi aanviel en Adarnase I van de pro-Byzantijnse Chosroid-dynastie installeerde, wat een periode van aanzienlijke Byzantijnse invloed markeerde.De opkomst van het moslimkalifaat en de daaropvolgende veroveringen in het Midden-Oosten verstoorden deze status quo echter al snel.De eerste Arabische invallen in wat nu Georgië is, vonden plaats tussen 642 en 645, tijdens hun

Arabische verovering van Perzië , waarbij Tbilisi in 645 in handen viel van de Arabieren. Hoewel de regio werd geïntegreerd in de nieuwe provincie Armīniya, behielden de lokale heersers aanvankelijk een niveau van macht. autonomie vergelijkbaar met wat ze hadden onder Byzantijns en Sassanidisch toezicht.De eerste jaren van de Arabische overheersing werden gekenmerkt door politieke instabiliteit binnen het kalifaat, dat moeite had om de controle over zijn uitgestrekte gebieden te behouden.Het belangrijkste instrument van het Arabische gezag in de regio was het opleggen van de jizya, een belasting die werd geheven op niet-moslims en die de onderwerping aan de islamitische heerschappij symboliseerde en bescherming bood tegen verdere invasies of strafmaatregelen.Op het Iberische schiereiland kwamen, net als in het naburige

Armenië , regelmatig opstanden tegen dit eerbetoon, vooral toen het kalifaat tekenen van interne zwakte vertoonde.Een belangrijke opstand vond plaats in 681-682, geleid door Adarnase II.Deze opstand, die deel uitmaakte van de bredere onrust in de Kaukasus, werd uiteindelijk neergeslagen;Adarnase werd gedood en de Arabieren installeerden Guaram II van de rivaliserende Guaramid-dynastie.Gedurende deze periode hadden de Arabieren ook te kampen met andere regionale machten, met name het Byzantijnse Rijk en de Khazaren – een confederatie van Turkse semi-nomadische stammen.Hoewel de Khazaren aanvankelijk een bondgenootschap hadden gesloten met Byzantium tegen Perzië, speelden ze later een dubbele rol door ook de Arabieren te helpen bij het onderdrukken van de Georgische opstand in 682. Het strategische belang van Georgische landen, gevangen tussen deze machtige buren, leidde tot herhaalde en destructieve invallen. vooral door de Khazaren uit het noorden.Het Byzantijnse rijk, dat zijn invloed op het Iberisch schiereiland wilde herbevestigen, concentreerde zich op het versterken van zijn controle over de kustgebieden van de Zwarte Zee, zoals Abchazië en Lazica, gebieden die nog niet door de Arabieren waren bereikt.In 685 onderhandelde keizer Justinianus II over een wapenstilstand met de kalief, waarbij hij overeenstemming bereikte over een gezamenlijk bezit van Iberia en Armenië.Deze regeling was echter van korte duur, aangezien de Arabische overwinning bij de Slag om Sebastopolis in 692 de regionale dynamiek aanzienlijk veranderde, wat leidde tot een nieuwe golf van Arabische veroveringen.Rond 697 hadden de Arabieren het koninkrijk Lazica onderworpen en hun bereik uitgebreid tot de Zwarte Zee, waardoor een nieuwe status quo werd gevestigd die het kalifaat bevoordeelde en zijn aanwezigheid in de regio verstevigde.

Emiraat Tbilisi (736-853)In de jaren 730 intensiveerde het Umayyad-kalifaat zijn controle over Georgië als gevolg van bedreigingen van de Khazaren en voortdurende contacten tussen lokale christelijke heersers en Byzantium.Onder kalief Hisham ibn Abd al-Malik en gouverneur Marwan ibn Muhammad werden agressieve campagnes gelanceerd tegen de Georgiërs en de Khazaren, met aanzienlijke gevolgen voor Georgië.De Arabieren vestigden een emiraat in Tbilisi, dat nog steeds te maken kreeg met weerstand van de lokale adel en een wisselende controle als gevolg van politieke instabiliteit binnen het kalifaat.Tegen het midden van de 8e eeuw verving het Abbasidische kalifaat de Umayyaden, met een meer gestructureerd bestuur en strengere maatregelen om eerbetoon veilig te stellen en de islamitische heerschappij af te dwingen, vooral onder leiding van de wali Khuzayma ibn Khazim.De Abbasiden kregen echter te maken met opstanden, met name van de Georgische prinsen, die ze bloedig onderdrukten.Gedurende deze periode verwierf de familie Bagrationi, waarschijnlijk van Armeense afkomst, bekendheid in West-Georgië en vestigde een machtsbasis in Tao-Klarjeti.Ondanks de Arabische overheersing slaagden ze erin een aanzienlijke autonomie te verwerven, waarbij ze profiteerden van de aanhoudende Arabisch-Byzantijnse conflicten en interne meningsverschillen onder de Arabieren.Aan het begin van de 9e eeuw verklaarde het emiraat Tbilisi zich onafhankelijk van het Abbasidische kalifaat, wat leidde tot verdere conflicten waarbij de Bagrationi betrokken waren, die een cruciale rol speelden in deze machtsstrijd.In 813 had Ashot I van de Bagrationi-dynastie het Principaat van Iberia hersteld met erkenning van zowel het kalifaat als de Byzantijnen.De regio kende een complex machtsspel, waarbij het kalifaat af en toe de Bagrationi steunde om het machtsevenwicht te behouden.Dit tijdperk eindigde met aanzienlijke Arabische nederlagen en verminderde invloed in de regio, waardoor de weg werd vrijgemaakt voor de Bagrationi om naar voren te komen als de dominante kracht in Georgië, wat de weg vrijmaakte voor de uiteindelijke eenwording van het land onder hun leiding.

Daling van de Arabische overheersingTegen het midden van de 9e eeuw nam de Arabische invloed in Georgië af, gekenmerkt door de verzwakking van het emiraat Tbilisi en de opkomst van sterke christelijke feodale staten in de regio, met name de Bagratiden van Armenië en Georgië.Het herstel van de monarchie in Armenië in 886, onder Bagratid Ashot I, liep parallel met de kroning van zijn neef Adarnase IV tot koning van Iberia, wat een heropleving van de christelijke macht en autonomie betekende.Gedurende deze periode zochten zowel het Byzantijnse rijk als het kalifaat de loyaliteit of neutraliteit van deze snelgroeiende christelijke staten om elkaars invloed te compenseren.Het Byzantijnse rijk onder

Basilius I de Macedoniër (reg. 867-886) beleefde een culturele en politieke renaissance die het tot een aantrekkelijke bondgenoot maakte voor de christelijke blanken, waardoor ze wegtrokken van het kalifaat.In 914 leidde Yusuf Ibn Abi'l-Saj, de emir van

Azerbeidzjan en een vazal van het kalifaat, de laatste belangrijke Arabische campagne om de dominantie over de Kaukasus te herbevestigen.Deze invasie, bekend als de Sajid-invasie van Georgië, mislukte en verwoestte het Georgische land verder, maar versterkte de alliantie tussen de Bagratiden en het Byzantijnse rijk.Deze alliantie maakte een periode van economische en artistieke bloei in Georgië mogelijk, vrij van Arabische inmenging.De invloed van de Arabieren bleef gedurende de 11e eeuw afnemen.Tbilisi bleef onder het nominale bewind van een emir staan, maar het bestuur van de stad kwam steeds meer in handen van een raad van oudsten, bekend als de ‘birebi’.Hun invloed hielp het emiraat in stand te houden als buffer tegen belastingheffing van de Georgische koningen.Ondanks pogingen van koning Bagrat IV om Tbilisi in 1046, 1049 en 1062 te veroveren, slaagde hij er niet in de controle te behouden.Tegen de jaren 1060 werden de Arabieren verdrongen door het Grote Seltsjoekse Rijk als de belangrijkste islamitische bedreiging voor Georgië.De beslissende verandering kwam in 1121 toen David IV van Georgië, bekend als "de Bouwer", de Seltsjoeken versloeg in de Slag bij Didgori, waardoor hij het jaar daarop Tbilisi kon veroveren.Deze overwinning maakte een einde aan bijna vijf eeuwen Arabische aanwezigheid in Georgië, waardoor Tbilisi als koninklijke hoofdstad werd geïntegreerd, hoewel de bevolking enige tijd overwegend moslim bleef.Dit markeerde het begin van een nieuw tijdperk van Georgische consolidatie en expansie onder inheemse heerschappij.