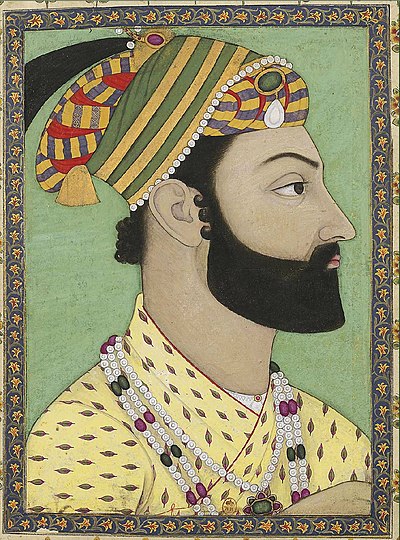

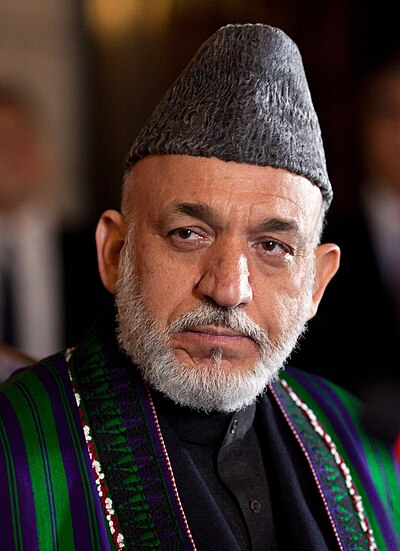

The Second Anglo-Afghan War (1878-1880) involved the British Raj and the Emirate of Afghanistan, under Sher Ali Khan of the Barakzai dynasty. It was part of the larger Great Game between Britain and Russia. The conflict unfolded in two main campaigns: the first started with the British invasion in November 1878, leading to Sher Ali Khan's flight. His successor, Mohammad Yaqub Khan, sought peace, culminating in the Treaty of Gandamak in May 1879. However, the British envoy in Kabul was killed in September 1879, rekindling the war. The second campaign concluded with the British defeating Ayub Khan in September 1880 near Kandahar. Abdur Rahman Khan was then installed as Amir, endorsing the Gandamak treaty and establishing the desired buffer against Russia, after which British forces withdrew.

Background

Following the Congress of Berlin in June 1878, which eased tensions between Russia and Britain in Europe, Russia shifted its focus to Central Asia, dispatching an unsolicited diplomatic mission to Kabul. Despite efforts by Sher Ali Khan, the Amir of Afghanistan, to prevent their entry, Russian envoys arrived on 22 July 1878. Subsequently, on 14 August, Britain demanded that Sher Ali also accept a British diplomatic mission. The Amir, however, refused to admit the mission led by Neville Bowles Chamberlain and threatened to obstruct it. In response, Lord Lytton, the Viceroy of India, sent a diplomatic mission to Kabul in September 1878. When this mission was turned back near the Khyber Pass's eastern entrance, it ignited the Second Anglo-Afghan War.

First Phase

The initial phase of the Second Anglo-Afghan War commenced in November 1878, with around 50,000 British forces, primarily Indian soldiers, entering Afghanistan through three distinct routes. Key victories at Ali Masjid and Peiwar Kotal left the pathway to Kabul almost unguarded. In response, Sher Ali Khan moved to Mazar-i-Sharif, aiming to stretch British resources thin across Afghanistan, hinder their southern occupation, and incite Afghan tribal uprisings, a strategy reminiscent of Dost Mohammad Khan and Wazir Akbar Khan during the First Anglo-Afghan War. With over 15,000 Afghan soldiers in Afghan Turkestan and preparations for further recruitment underway, Sher Ali sought Russian aid but was denied entry into Russia and advised to negotiate surrender with the British. He returned to Mazar-i-Sharif, where his health deteriorated, leading to his death on 21 February 1879.

Prior to heading to Afghan Turkestan, Sher Ali released several long-imprisoned governors, promising the restoration of their states for their support against the British. However, disillusioned by past betrayals, some governors, notably Muhammad Khan of Sar-I-Pul and Husain Khan of the Maimana Khanate, declared independence and expelled Afghan garrisons, triggering Turkmen raids and further instability.

Sher Ali's demise ushered in a succession crisis. Muhammad Ali Khan's attempt to seize Takhtapul was thwarted by a mutinous garrison, forcing him southward to muster an opposing force. Yaqub Khan was then proclaimed Amir, amid arrests of sardars suspected of Afzalid allegiance. Under the occupation of British forces in Kabul, Yaqub Khan, the son and successor of Sher Ali, consented to the Treaty of Gandamak on 26 May 1879. This treaty mandated Yaqub Khan to relinquish Afghan foreign affairs to British control in exchange for an annual subsidy and uncertain promises of support against foreign invasion. The treaty also established British representatives in Kabul and other strategic locations, gave Britain control over the Khyber and Michni passes, and led to Afghanistan ceding territories including Quetta and the fort of Jamrud in the North-West Frontier Province to Britain. Additionally, Yaqub Khan agreed to cease any interference in the internal matters of the Afridi tribe. In return, he was to receive an annual subsidy of 600,000 rupees, with Britain agreeing to withdraw all its forces from Afghanistan, excluding Kandahar.

However, the agreement's fragile peace was shattered on 3 September 1879 when an uprising in Kabul resulted in the assassination of Sir Louis Cavagnari, the British envoy, along with his guards and staff. This incident reignited hostilities, marking the commencement of the Second Anglo-Afghan War's next phase.

Second Phase

In the first campaign's climax, Major General Sir Frederick Roberts led the Kabul Field Force through the Shutargardan Pass, defeating the Afghan Army at Charasiab on 6 October 1879, and occupied Kabul shortly after. A significant uprising led by Ghazi Mohammad Jan Khan Wardak attacked British forces near Kabul in December 1879 but was quelled after a failed assault on 23 December. Yaqub Khan, implicated in the Cavagnari massacre, was forced to abdicate. The British deliberated over Afghanistan's future governance, considering various successors, including partitioning the country or installing Ayub Khan or Abdur Rahman Khan as Amir.

Abdur Rahman Khan, in exile and initially barred by the Russians from entering Afghanistan, capitalized on the political vacuum post-Yaqub Khan's abdication and the British occupation of Kabul. He traversed to Badakhshan, bolstered by marriage ties and a claimed visionary encounter, capturing Rostaq and annexing Badakhshan after a successful military campaign. Despite initial resistance, Abdur Rahman consolidated control over Afghan Turkestan, aligning with forces opposed to Yaqub Khan's appointees.

The British sought a stable ruler for Afghanistan, identifying Abdur Rahman as a potential candidate despite his resistance and the insistence on jihad from his followers. Amidst negotiations, the British aimed for a swift resolution to withdraw forces, influenced by the administrative change from Lytton to the Marquis of Ripon. Abdur Rahman, leveraging the British desire for withdrawal, solidified his position and was recognized as Amir in July 1880, after securing support from various tribal leaders.

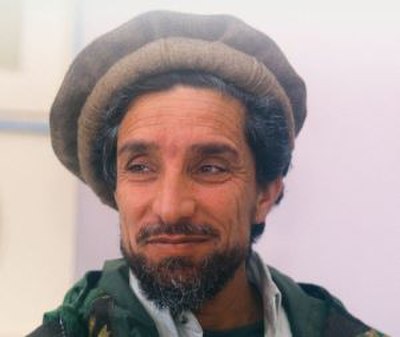

Simultaneously, Ayub Khan, the governor of Herat, rebelled, notably at the Battle of Maiwand in July 1880, but was ultimately defeated by Roberts' forces at the Battle of Kandahar on 1 September 1880, quashing his insurrection and concluding his challenge to British and Abdur Rahman's authority.

Aftermath

After Ayub Khan's defeat, the Second Anglo-Afghan War concluded with Abdur Rahman Khan emerging as the victor and the new Amir of Afghanistan. In a significant turn, the British, despite initial reluctance, returned Kandahar to Afghanistan and Rahman reaffirmed the Treaty of Gandamak, which saw Afghanistan cede territorial control to the British but regain autonomy over its internal affairs. This treaty also marked the end of the British ambition to maintain a resident in Kabul, opting instead for indirect liaison through British Indian Muslim agents and control over Afghanistan's foreign policy in return for protection and a subsidy. These measures, ironically in line with Sher Ali Khan's earlier desires, established Afghanistan as a buffer state between the British Raj and Russian Empire, potentially avoidable had they been applied sooner.

The war proved costly for Britain, with expenses ballooning to approximately 19.5 million pounds by March 1881, far exceeding initial estimates. Despite Britain's intent to safeguard Afghanistan from Russian influence and establish it as an ally, Abdur Rahman Khan adopted an autocratic rule reminiscent of Russian Tsars and frequently acted in defiance of British expectations. His reign, marked by severe measures including atrocities that shocked even Queen Victoria, earned him the moniker 'Iron Amir'. Abdur Rahman's governance, characterized by secrecy about military capabilities and direct diplomatic engagements contrary to agreements with Britain, challenged British diplomatic efforts. His advocacy for Jihad against both British and Russian interests further strained relations.

However, no significant conflicts arose between Afghanistan and British India during Abdur Rahman's rule, with Russia maintaining a distance from Afghan affairs except for the Panjdeh incident, which was resolved diplomatically. The establishment of the Durand Line in 1893 by Mortimer Durand and Abdur Rahman, demarcating the spheres of influence between Afghanistan and British India, fostered improved diplomatic relations and trade, while creating the North-West Frontier Province, solidifying the geopolitical landscape between the two entities.