History of Republic of Pakistan

The Islamic Republic of Pakistan was established on 14 August 1947, emerging from the partition of India as part of the British Commonwealth. This event marked the creation of two separate nations, Pakistan and India, based on religious lines. Pakistan initially consisted of two geographically separate areas, West Pakistan (current Pakistan) and East Pakistan (now Bangladesh), as well as Hyderabad, now part of India.

The historical narrative of Pakistan, as officially recognized by the government, traces its roots back to the Islamic conquests in the Indian subcontinent, starting with Muhammad bin Qasim in the 8th century CE, and reaching a pinnacle during the Mughal Empire.

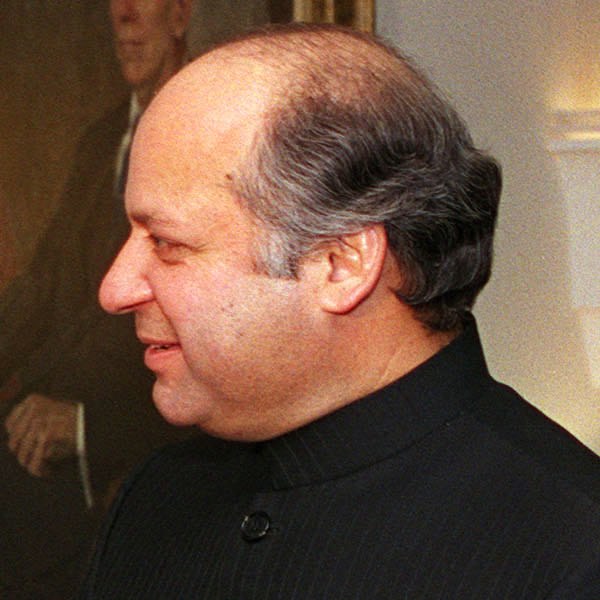

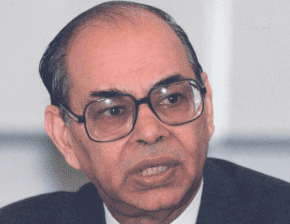

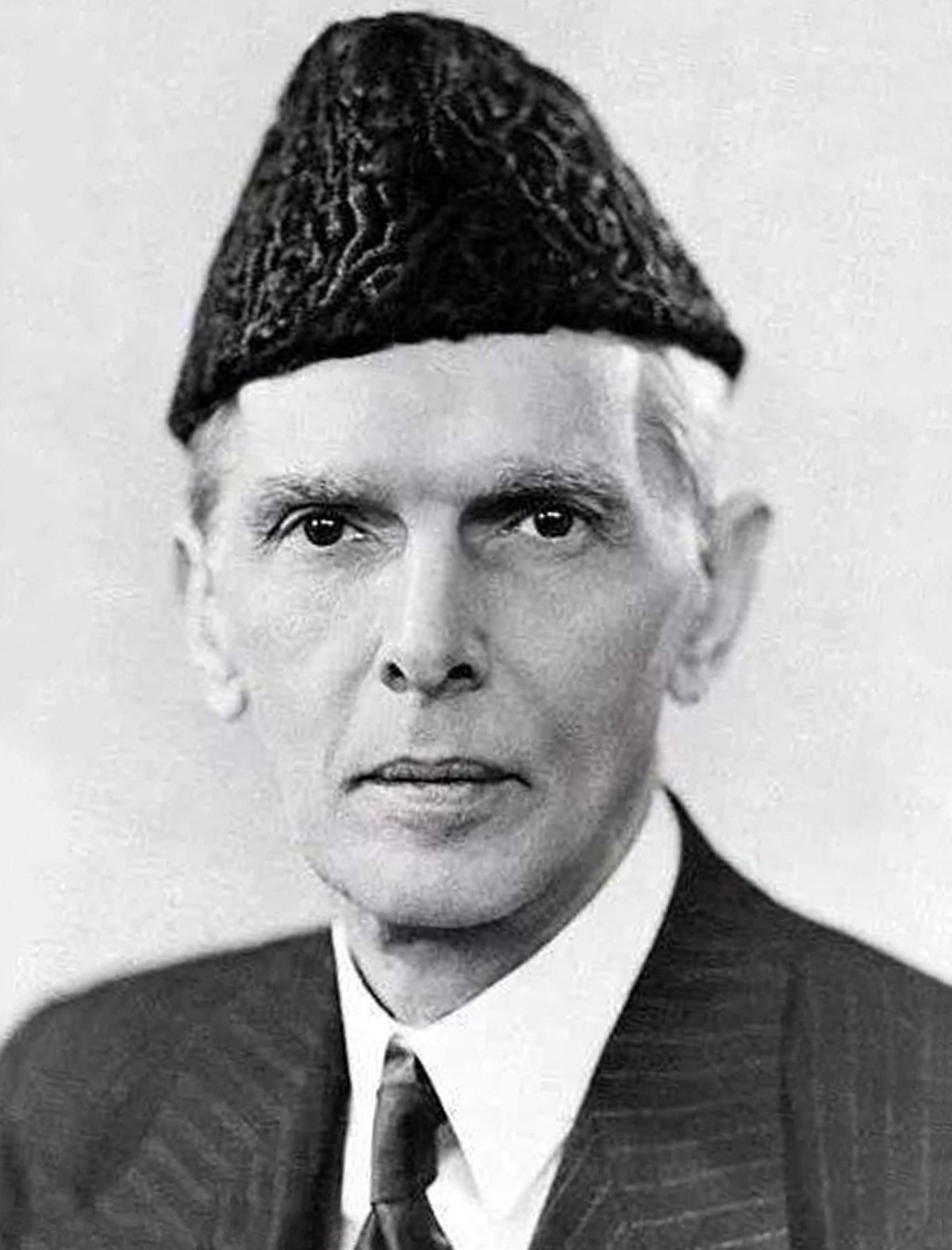

Muhammad Ali Jinnah, the leader of the All-India Muslim League, became Pakistan's first Governor-General, while Liaquat Ali Khan, the secretary-general of the same party, became the Prime Minister. In 1956, Pakistan adopted a constitution that declared the country an Islamic democracy.

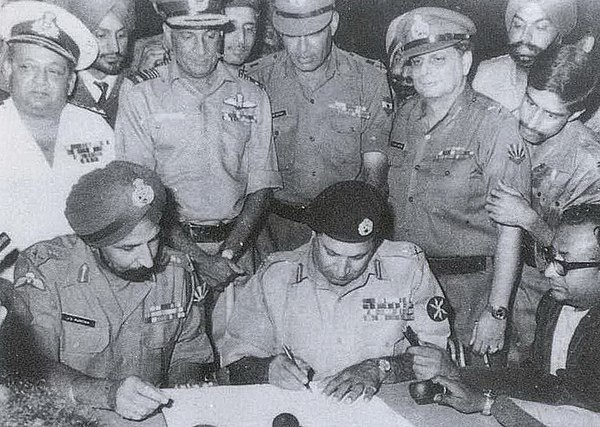

However, the country faced significant challenges. In 1971, after a civil war and Indian military intervention, East Pakistan seceded to become Bangladesh. Pakistan has also been involved in several conflicts with India, mainly over territorial disputes.

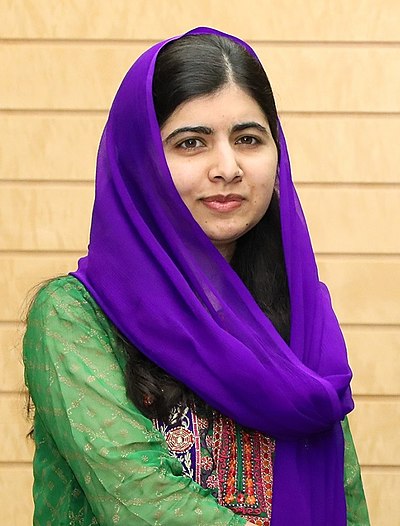

During the Cold War, Pakistan aligned closely with the United States, playing a crucial role in the Afghan-Soviet War by supporting Sunni Mujahideens. This conflict had a profound impact on Pakistan, contributing to issues like terrorism, economic instability, and infrastructure damage, particularly between 2001 and 2009.

Pakistan is a nuclear-weapon state, having conducted six nuclear tests in 1998, in response to India's nuclear tests. This position places Pakistan as the seventh country worldwide to develop nuclear weapons, the second in South Asia, and the only one in the Islamic world.

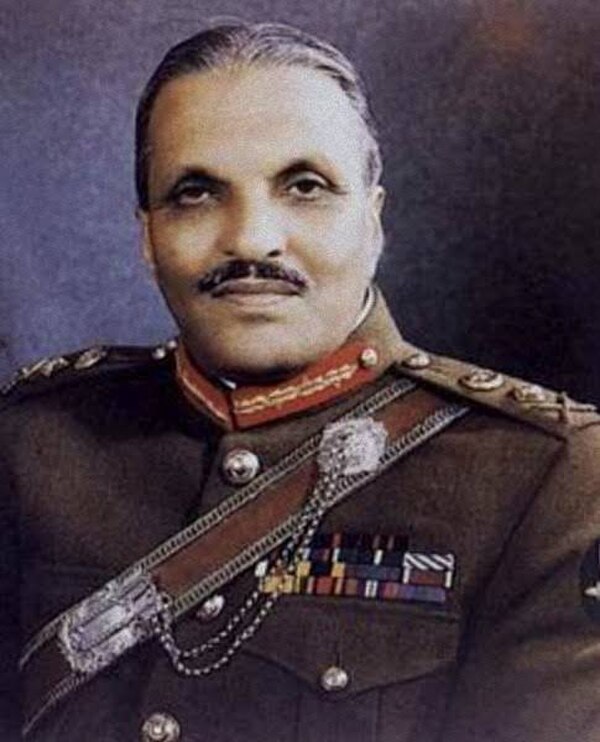

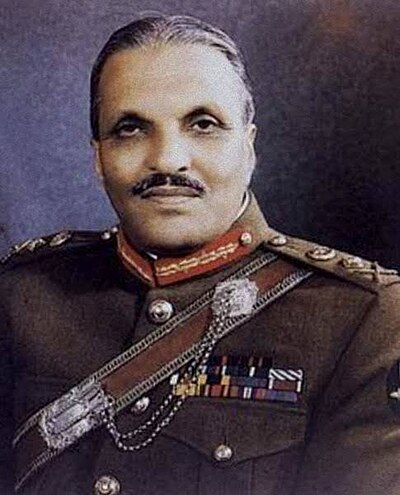

The country's military is significant, with one of the largest standing forces globally. Pakistan is also a founding member of several international organizations, including the Organisation of Islamic Cooperation (OIC), the South Asian Association for Regional Cooperation (SAARC), and the Islamic Military Counter Terrorism Coalition.

Economically, Pakistan is recognized as a regional and middle power with a growing economy. It is part of the "Next Eleven" countries, identified as having the potential to become among the world's largest economies in the 21st century. The China-Pakistan Economic Corridor (CPEC) is expected to play a vital role in this development. Geographically, Pakistan holds a strategic position, linking the Middle East, Central Asia, South Asia, and East Asia.