History of the Ottoman Empire

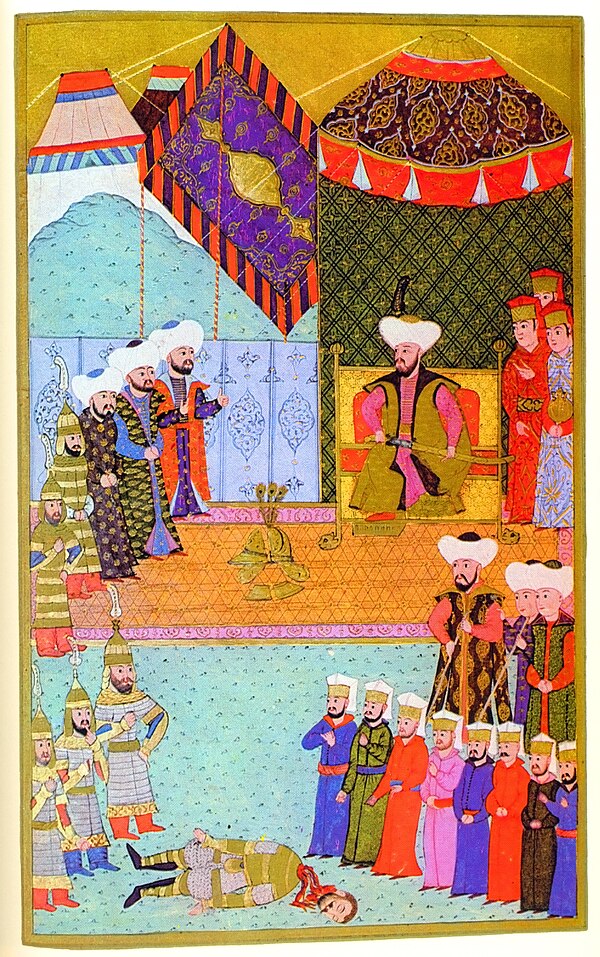

The Ottoman Empire was founded c. 1299 by Osman I as a small beylik in northwestern Asia Minor just south of the Byzantine capital Constantinople. In 1326, the Ottomans captured nearby Bursa, cutting off Asia Minor from Byzantine control. The Ottomans first crossed into Europe in 1352, establishing a permanent settlement at Çimpe Castle on the Dardanelles in 1354 and moving their capital to Edirne (Adrianople) in 1369. At the same time, the numerous small Turkic states in Asia Minor were assimilated into the budding Ottoman sultanate through conquest or declarations of allegiance.

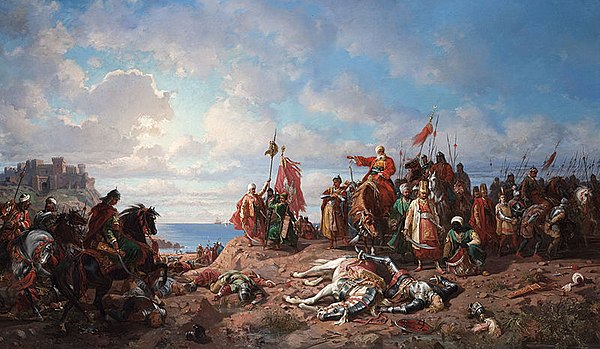

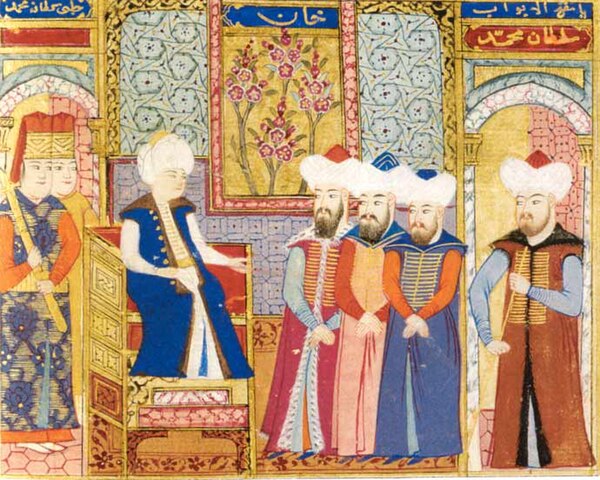

As Sultan Mehmed II conquered Constantinople (today named Istanbul) in 1453, transforming it into the new Ottoman capital, the state grew into a substantial empire, expanding deep into Europe, northern Africa and the Middle East. With most of the Balkans under Ottoman rule by the mid-16th century, Ottoman territory increased exponentially under Sultan Selim I, who assumed the Caliphate in 1517 as the Ottomans turned east and conquered western Arabia, Egypt, Mesopotamia and the Levant, among other territories. Within the next few decades, much of the North African coast (except Morocco) became part of the Ottoman realm.

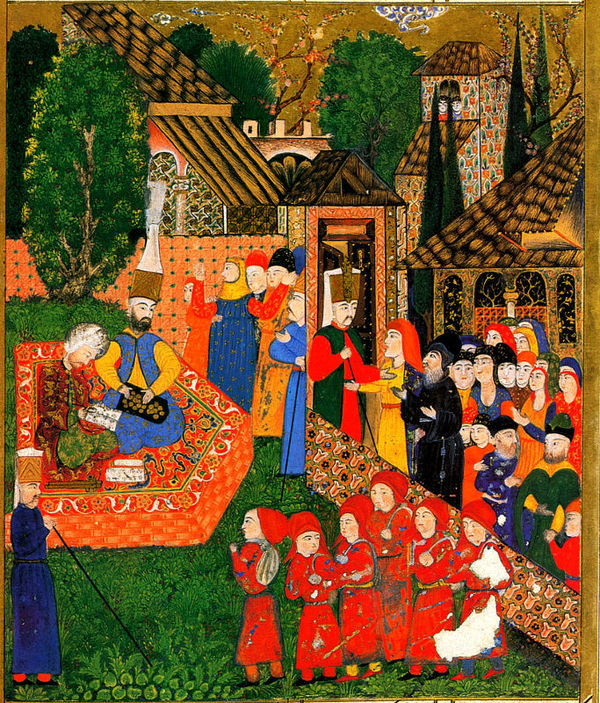

The empire reached its apex under Suleiman the Magnificent in the 16th century, when it stretched from the Persian Gulf in the east to Algeria in the west, and from Yemen in the south to Hungary and parts of Ukraine in the north. According to the Ottoman decline thesis, Suleiman's reign was the zenith of the Ottoman classical period, during which Ottoman culture, arts, and political influence flourished. The empire reached its maximum territorial extent in 1683, on the eve of the Battle of Vienna.

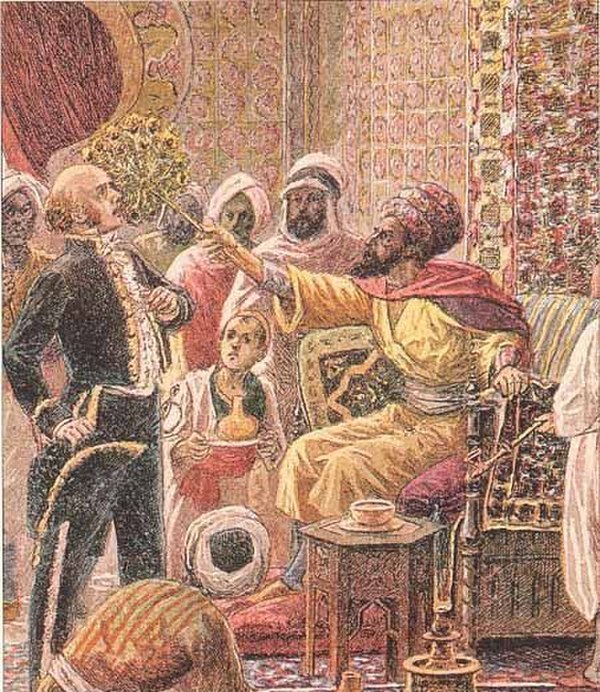

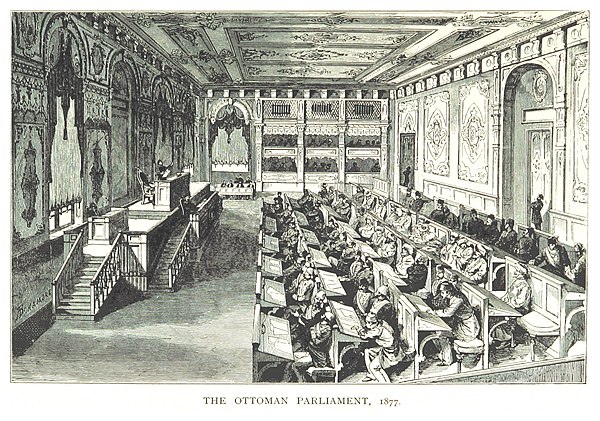

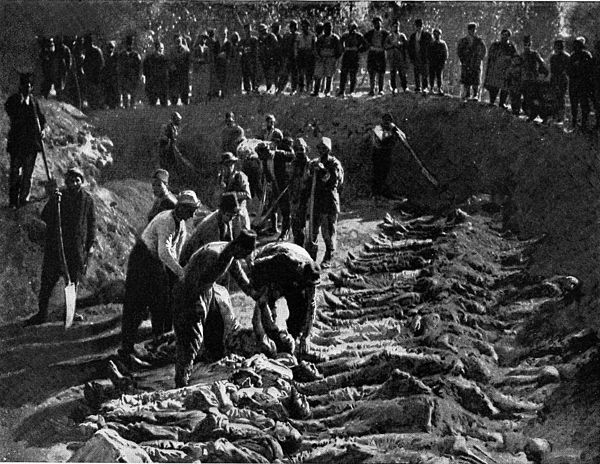

From 1699 onwards, the Ottoman Empire began to lose territory over the course of the next two centuries due to internal stagnation, costly defensive wars, European colonialism, and nationalist revolts among its multiethnic subjects. In any case, the need to modernize was evident to the empire's leaders by the early 19th century, and numerous administrative reforms were implemented in an attempt to forestall the decline of the empire, with varying degrees of success. The gradual weakening of the Ottoman Empire gave rise to the Eastern Question in the mid-19th century.

The empire came to an end in the aftermath of its defeat in World War I, when its remaining territory was partitioned by the Allies. The sultanate was officially abolished by the Government of the Turkish Grand National Assembly in Ankara on 1 November 1922 following the Turkish War of Independence. Throughout its more than 600 years of existence, the Ottoman Empire has left a profound legacy in the Middle East and Southeast Europe, as can be seen in the customs, culture, and cuisine of the various countries that were once part of its realm.

_(Nachfolger)_-_Sultan_Orhan_-_2236_-_69_x_54_cm._Bavarian_State_Painting_Collections._Munich,_Germany.jpg/400px-Paolo_Veronese_(1528-1588)_(Nachfolger)_-_Sultan_Orhan_-_2236_-_69_x_54_cm._Bavarian_State_Painting_Collections._Munich,_Germany.jpg)