Safavid Persia

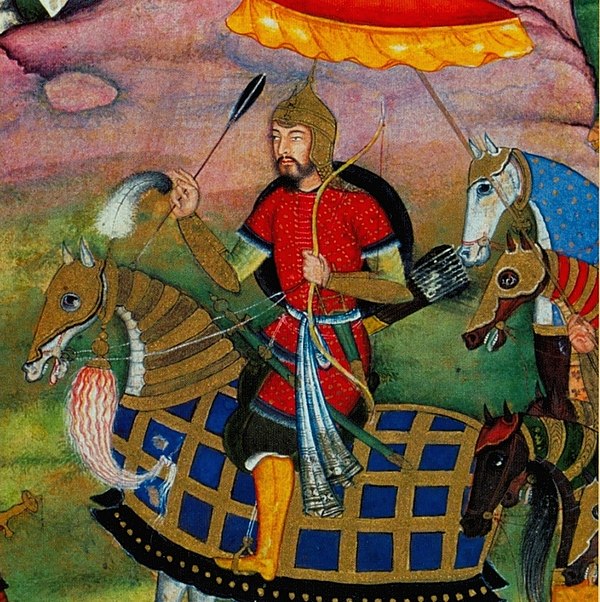

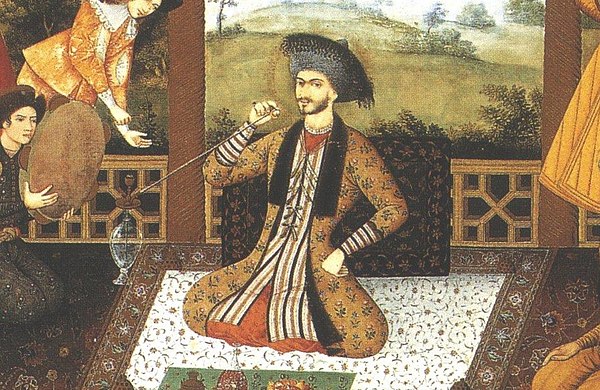

Safavid Persia, also referred to as the Safavid Empire, was one of the greatest Iranian empires after the 7th-century Muslim conquest of Persia, which was ruled from 1501 to 1736 by the Safavid dynasty. It is often considered the beginning of modern Iranian history, as well as one of the gunpowder empires. The Safavid Shāh Ismā'īl I established the Twelver denomination of Shīʿa Islam as the official religion of the empire, marking one of the most important turning points in the history of Islam.

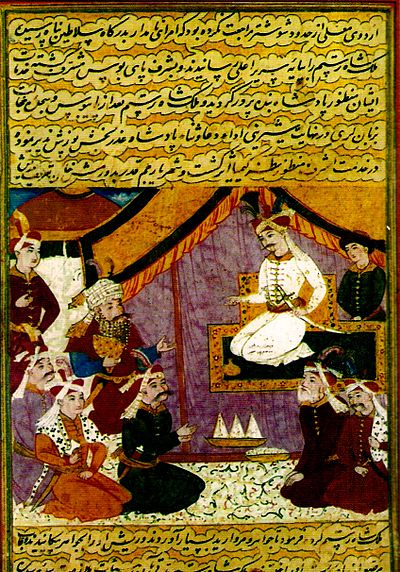

The Safavid dynasty had its origin in the Safavid order of Sufism, which was established in the city of Ardabil in the Azerbaijan region. It was an Iranian dynasty of Kurdish origin but during their rule they intermarried with Turkoman, Georgian, Circassian, and Pontic Greek dignitaries, nevertheless they were Turkish-speaking and Turkified. From their base in Ardabil, the Safavids established control over parts of Greater Iran and reasserted the Iranian identity of the region, thus becoming the first native dynasty since the Buyids to establish a national state officially known as Iran.

The Safavids ruled from 1501 to 1722 (experiencing a brief restoration from 1729 to 1736 and 1750 to 1773) and, at their height, they controlled all of what is now Iran, Republic of Azerbaijan, Bahrain, Armenia, eastern Georgia, parts of the North Caucasus including Russia, Iraq, Kuwait, and Afghanistan, as well as parts of Turkey, Syria, Pakistan, Turkmenistan, and Uzbekistan.

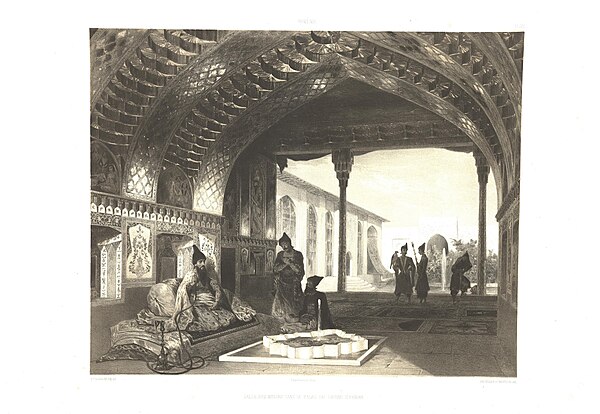

Despite their demise in 1736, the legacy that they left behind was the revival of Iran as an economic stronghold between East and West, the establishment of an efficient state and bureaucracy based upon "checks and balances", their architectural innovations, and patronage for fine arts. The Safavids have also left their mark down to the present era by establishing Twelver Shīʿīsm as the state religion of Iran, as well as spreading Shīʿa Islam in major parts of the Middle East, Central Asia, Caucasus, Anatolia, the Persian Gulf, and Mesopotamia.