Vietnam War

The Vietnam War took place in Vietnam, Laos and Cambodia from November 1 1955, to the fall of Saigon on April 30 1975. It played a role during the Cold War period. Was part of the broader Indochina Wars. While it was officially a dispute between North and South Vietnam it evolved into a larger scale conflict with North Vietnam receiving support from countries like the Soviet Union and China among others favoring communism. On the side South Vietnam had backing from the United States and its anti communist allies. This prolonged conflict spanned two decades before direct U.S. Military involvement ended in 1973. The repercussions of this war were felt beyond borders as neighboring countries such as Laos and Cambodia experienced strife leading all three nations to embrace communism by 1976.

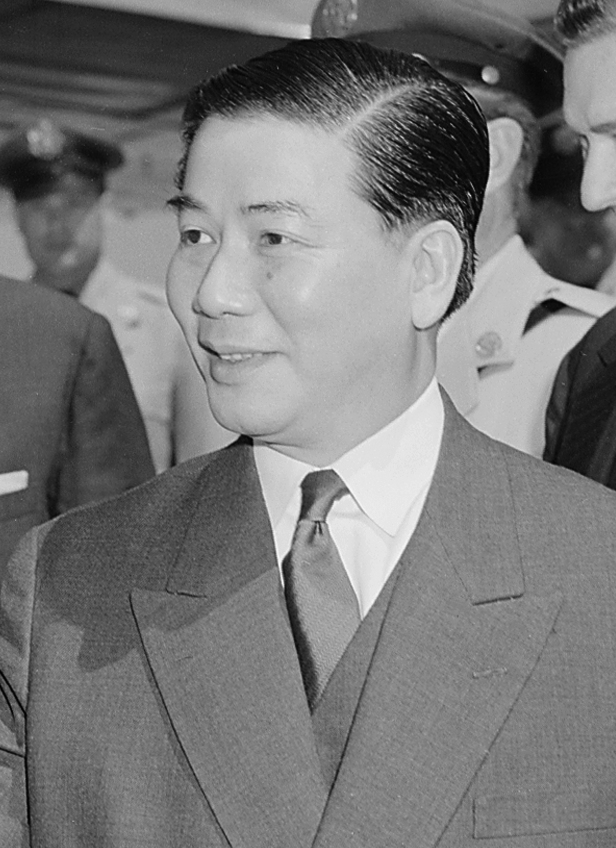

In the aftermath of French Indochinas dissolution following the Geneva Conference in July 1954 Vietnam emerged as an entity. Was partitioned into two separate regions; North Vietnam under Viet Minh control and South Vietnam backed by U.S. Military assistance. Subsequently the Viet Cong (VC) an organization operating in South Vietnam with affiliations to ideals initiated guerrilla warfare activities within that region. The Peoples Army of Vietnam (PAVN) also recognized as the North Vietnamese Army (NVA) engaged in combat, against U.S. Forces alongside those of the Army of the Republic of Vietnam (ARVN). In 1958 North Vietnam ventured into Laos. Created the Ho Chi Minh Trail to assist and strengthen the VC. 40,000 soldiers were dispatched from the north to join the fight, in the south by 1963. The U.S. Became more involved during President John F. Kennedys administration with military advisors increasing from than a thousand in 1959 to 23,000 by 1964.

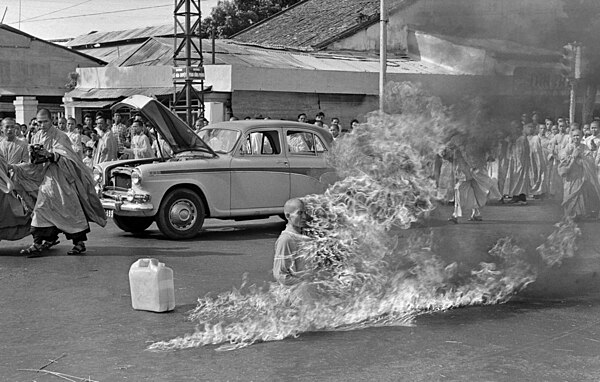

Following the Gulf of Tonkin incident in August 1964 a resolution approved by the U.S. Congress granted President Lyndon B. Johnson the power to escalate presence in Vietnam without a declaration of war. Johnson ordered combat units to be sent for the time and significantly boosted troop levels to 184,000. The U.S. And South Vietnamese forces relied on air superiority and superior firepower for search. Destroy missions involving ground troops, artillery and airstrikes. Moreover there was a bombing campaign against North Vietnam by the U.S., which continued building its forces despite facing progress. The Tet Offensive was initiated by forces in 1968.

Although they encountered setbacks initially it eventually proved advantageous as it led to decreased support for the war, in the United States. By the end of that year most of VCs territory had been lost as they were overshadowed by PAVN forces. In 1969 North Vietnam established the Provisional Revolutionary Government of South Vietnam. Military operations expanded beyond borders involving the U.S. focusing on disrupting supply routes in Laos and Cambodia through airstrikes. The ousting of Cambodian ruler Norodom Sihanouk, in 1970 led to an invasion into Cambodia at the request of the Khmer Rouge countered by U.S. And ARVN forces escalating the Cambodian Civil War. Following Richard Nixons election in 1969 a strategy called "Vietnamization" was launched, transferring combat duties to an ARVN as U.S. Troops gradually withdrew due to growing opposition. By 1972 most U.S. Ground forces had left Vietnam shifting their involvement to air support, advisory roles and equipment provision. The signing of the Paris Peace Accords in January 1973 signaled the departure of U.S. Forces from Vietnam; however violations arose immediately. Hostilities persisted for another two years. The Khmer Rouge seized control of Phnom Penh on April 17 1975 while Saigon fell to PAVN on April 30th marking the end of the conflict. Vietnam was reunified on July 2nd that year.

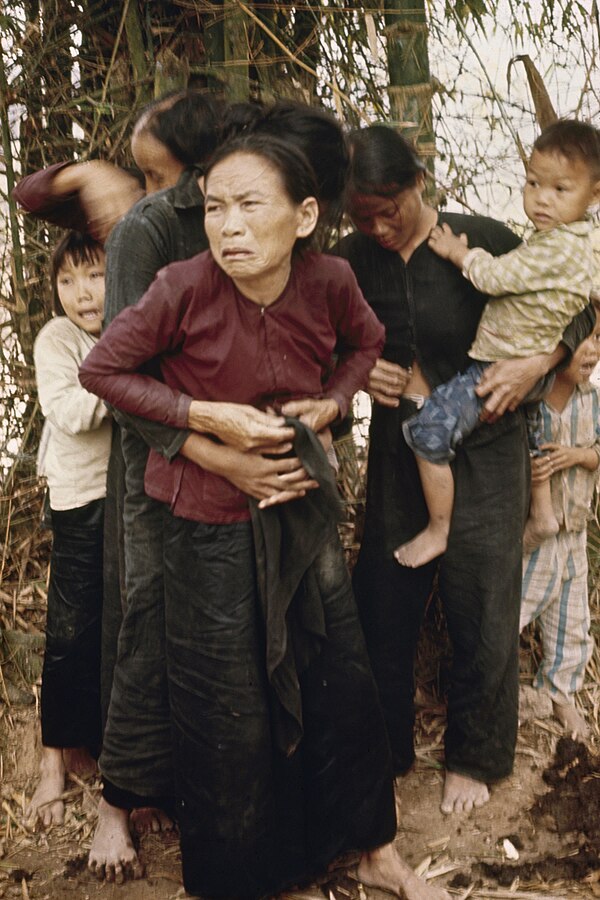

The war resulted in loss of life; estimates indicate that between 966,000 to 3 million Vietnamese soldiers and civilians perished during this period. Additionally 275,000–310,000 Cambodians, 20 62 thousand Laotians and, around 58,220 U.S. Service members lost their lives throughout the duration of the conflict. The conclusion of the Vietnam War triggered a mass exodus of boat people causing a refugee crisis, in Indochina as millions sought safety with a loss of 250,000 lives at sea. Following their rise to power the Khmer Rouge regime orchestrated a genocide. The mounting tensions between them and unified Vietnam eventually escalated into the Vietnamese War resulting in the overthrow of the Khmer Rouge government in 1979 and bringing an end, to the genocide. Subsequently China initiated an invasion into Vietnam which led to prolonged border conflicts until 1991.