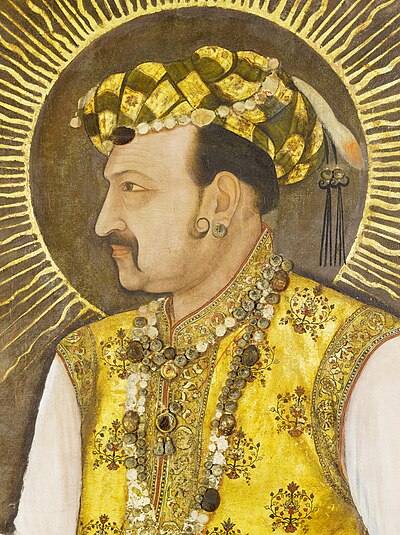

Mughal Empire

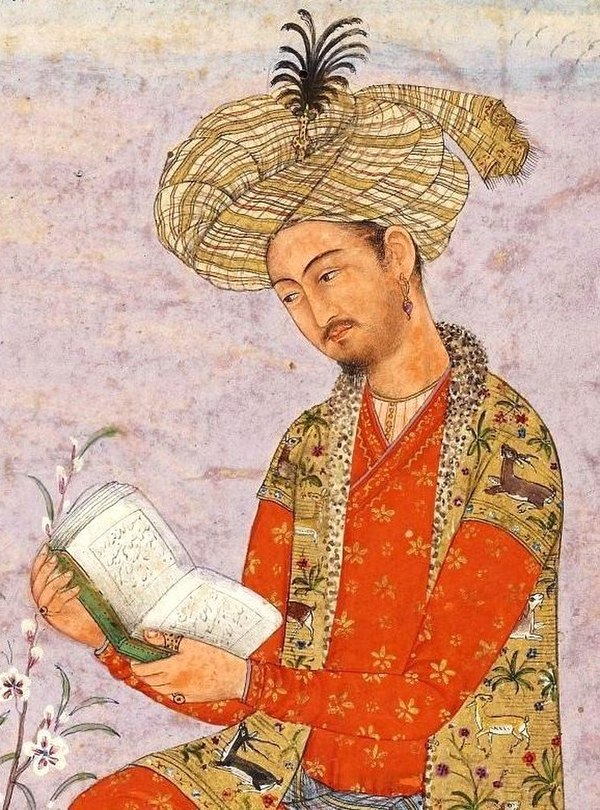

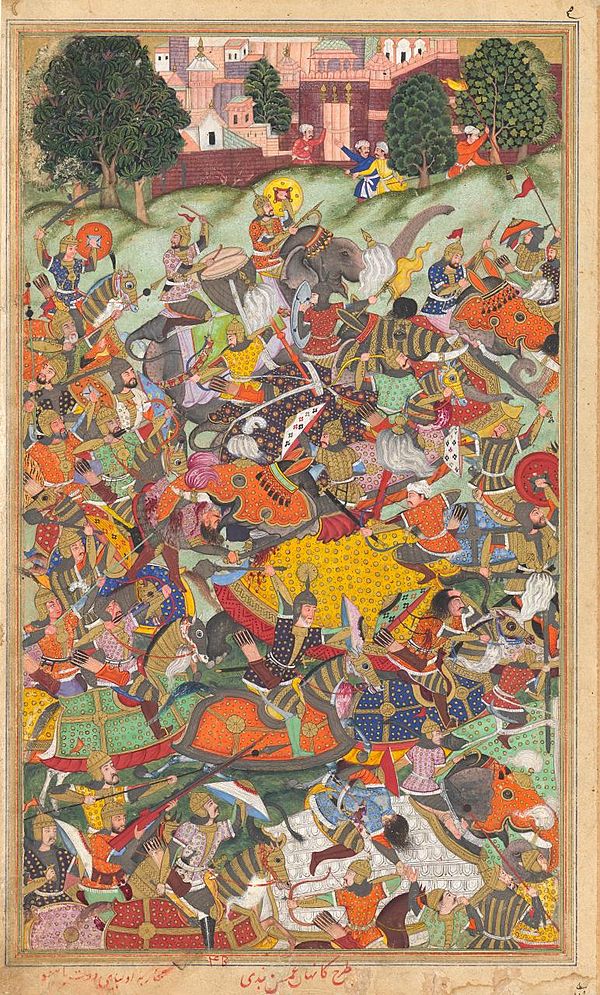

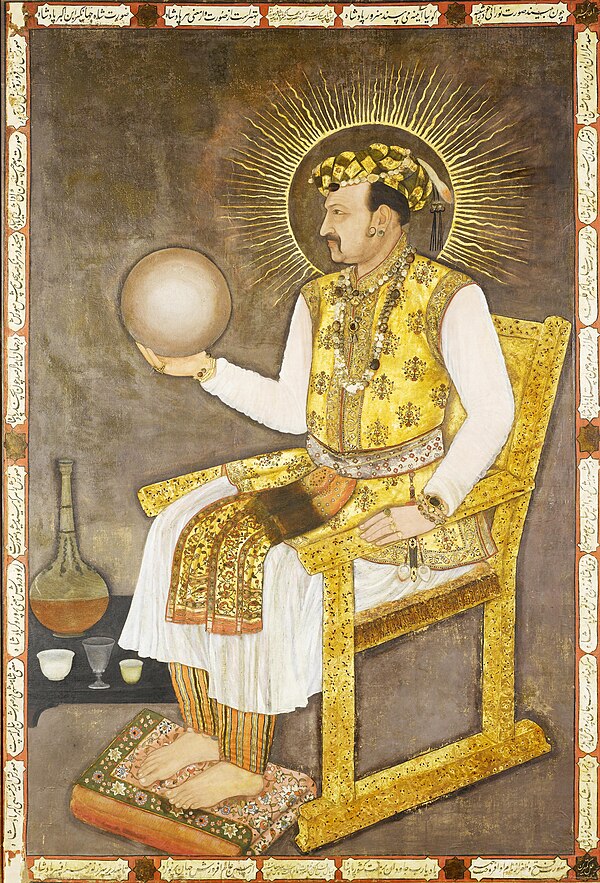

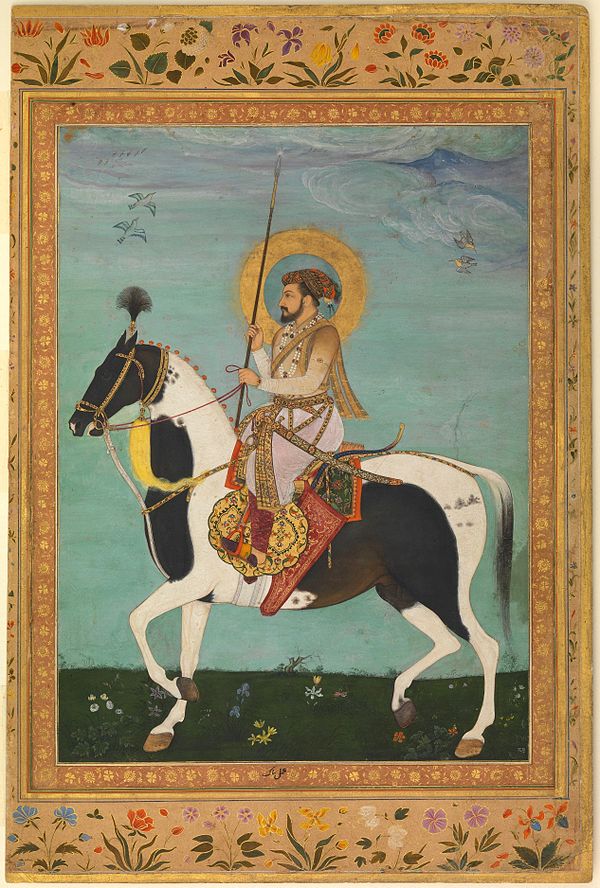

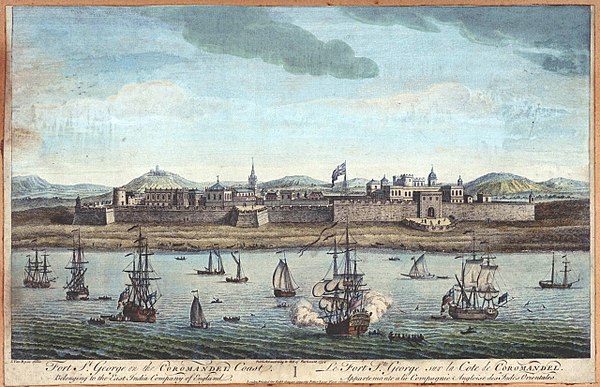

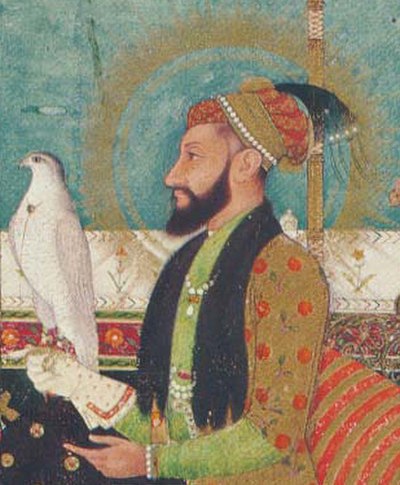

The Mughal Empire, founded in 1526 by Babur, a chieftain from present-day Uzbekistan, marked a significant era in South Asia. Babur, with aid from the Safavid and Ottoman Empires, defeated the Sultan of Delhi, Ibrahim Lodi, at the First Battle of Panipat, establishing his rule in North India. The empire's formal imperial structure is often dated from 1600 under Akbar, Babur's grandson, and lasted until about 1720, after the death of Aurangzeb, the last major emperor. Aurangzeb's reign saw the empire reach its greatest territorial extent. By 1760, the empire's control had significantly diminished to the region around Old Delhi, and it was formally dissolved by the British following the Indian Rebellion of 1857.

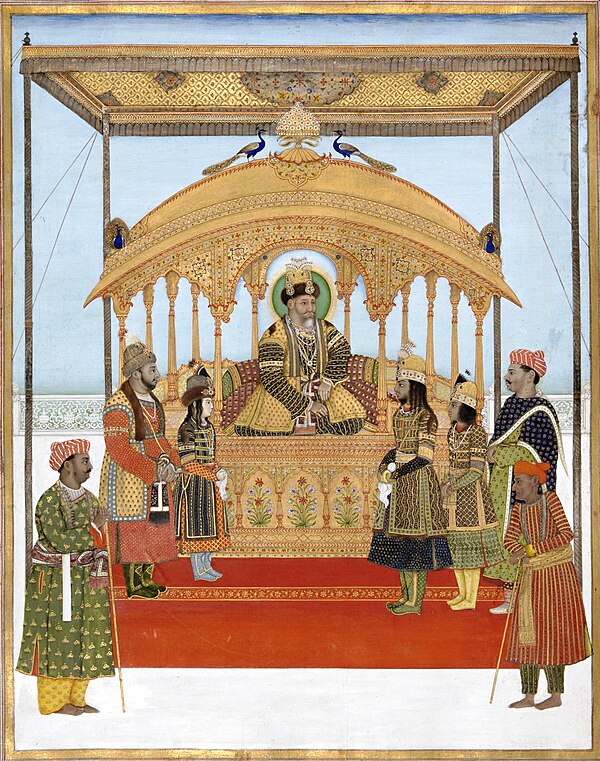

The Mughal Empire, known for its military origins, was also notable for its inclusive approach towards the diverse cultures and peoples it governed. It introduced new administrative practices that helped standardize and centralize governance, making it more efficient. The empire's economy was largely based on agricultural taxes, established by Akbar, which were a major source of revenue and helped integrate peasants and artisans into larger markets.

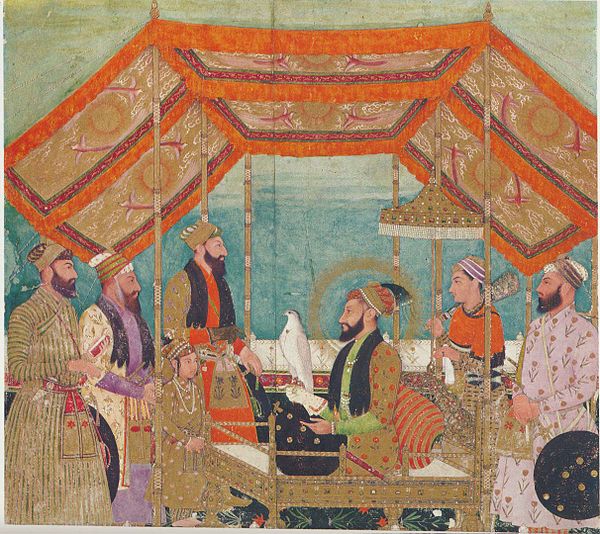

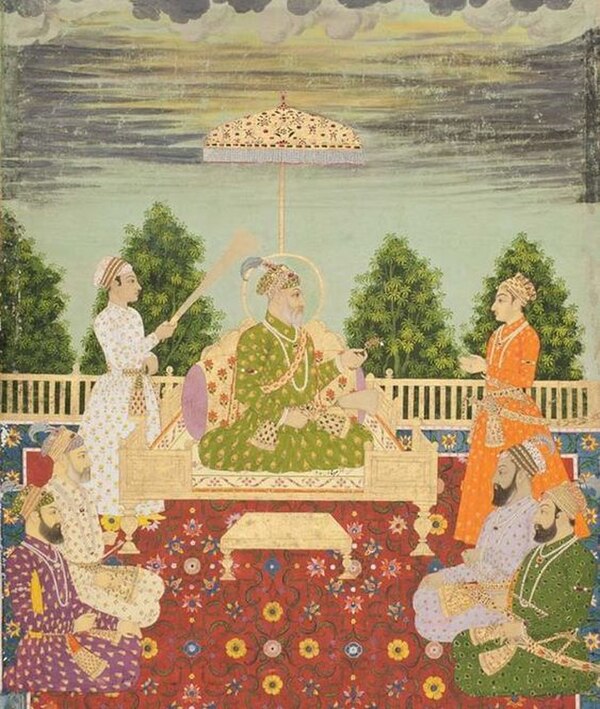

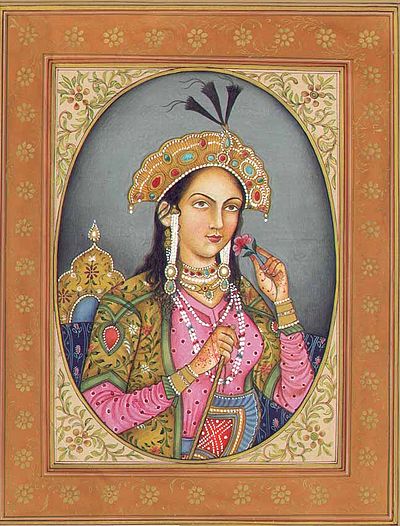

Throughout the 17th century, the Mughal Empire maintained relative peace, contributing to economic prosperity and making it a period of cultural renaissance. This era saw significant European interest in Indian products, enhancing the empire's wealth. The Mughals were great patrons of art and architecture, fostering the development of unique styles in painting, literature, textiles, and architecture.