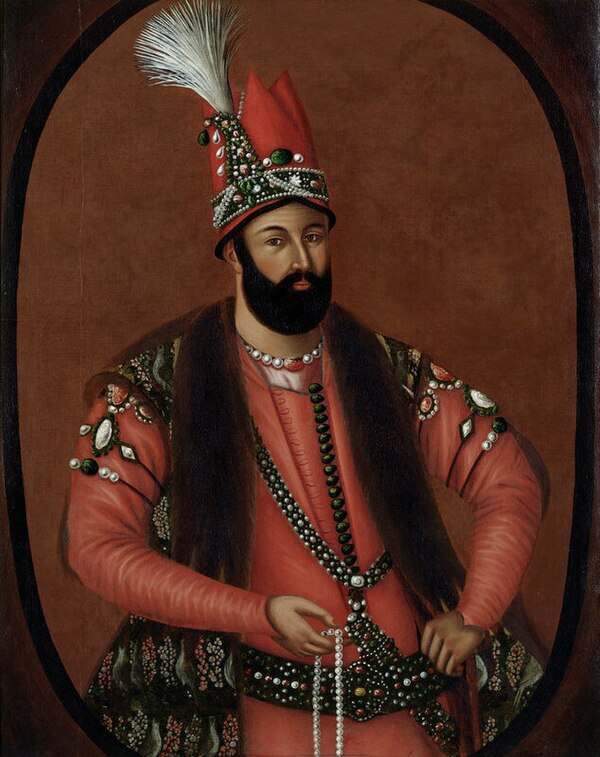

Agha Mohammad Khan, after emerging victorious from the civil war following the last Zand king's demise, focused on reuniting and centralizing Iran.[54] Post-Nader Shah and the Zand era, Iran's Caucasian territories had formed various khanates. Agha Mohammad Khan aimed to reincorporate these regions into Iran, considering them as integral as any mainland territory.

One of his primary targets was Georgia, which he viewed as crucial to Iranian sovereignty. He demanded that the Georgian king, Erekle II, renounce his 1783 treaty with Russia and reaccept Persian suzerainty, which Erekle II refused. In response, Agha Mohammad Khan launched a military campaign, successfully reasserting Iranian control over various Caucasian territories, including modern-day Armenia, Azerbaijan, Dagestan, and Igdir. He triumphed in the Battle of Krtsanisi, leading to the capture of Tbilisi and the effective resubjugation of Georgia.[55]

In 1796, after returning from his successful campaign in Georgia and transporting thousands of Georgian captives to Iran, Agha Mohammad Khan was formally crowned Shah. His reign was cut short by assassination in 1797 while planning another expedition against Georgia. Following his death, Russia capitalized on the regional instability. In 1799, Russian forces entered Tbilisi, and by 1801, they had effectively annexed Georgia. This expansion marked the beginning of the Russo-Persian Wars (1804-1813 and 1826–1828), leading to the eventual cession of eastern Georgia, Dagestan, Armenia, and Azerbaijan to Russia, as stipulated in the Treaties of Gulistan and Turkmenchay. Thus, the territories north of the Aras River, including contemporary Azerbaijan, eastern Georgia, Dagestan, and Armenia, remained part of Iran until their 19th-century occupation by Russia.[56]

Following the Russo-Persian Wars and the official loss of vast territories in the Caucasus, significant demographic shifts occurred. The wars of 1804–1814 and 1826–1828 led to large migrations known as Caucasian Muhajirs to mainland Iran. This movement included various ethnic groups such as Ayrums, Qarapapaqs, Circassians, Shia Lezgins, and other Transcaucasian Muslims.[57] Post the Battle of Ganja in 1804, many Ayrums and Qarapapaqs were resettled in Tabriz, Iran. Throughout the 1804–1813 war, and later during the 1826–1828 conflict, more of these groups from the newly conquered Russian territories migrated to Solduz in present-day West Azerbaijan province, Iran.[58] The Russian military activities and governance issues in the Caucasus drove large numbers of Muslims and some Georgian Christians into exile in Iran.[59]

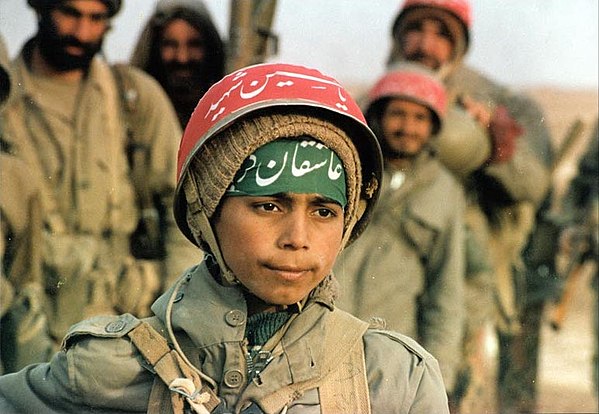

From 1864 until the early 20th century, further expulsions and voluntary migrations occurred following the Russian victory in the Caucasian War. This led to additional movements of Caucasian Muslims, including Azerbaijani, other Transcaucasian Muslims, and North Caucasian groups like Circassians, Shia Lezgins, and Laks, towards Iran and Turkey.[57] Many of these migrants played crucial roles in Iran's history, forming a significant part of the Persian Cossack Brigade established in the late 19th century.[60]

The Treaty of Turkmenchay in 1828 also facilitated the resettlement of Armenians from Iran to the newly Russian-controlled territories.[61] Historically, Armenians were a majority in Eastern Armenia but became a minority following Timur's campaigns and subsequent Islamic dominance.[62] The Russian invasion of Iran further altered the ethnic composition, leading to an Armenian majority in Eastern Armenia by 1832. This demographic shift was further solidified after the Crimean War and the Russo-Turkish War of 1877–1878.[63]

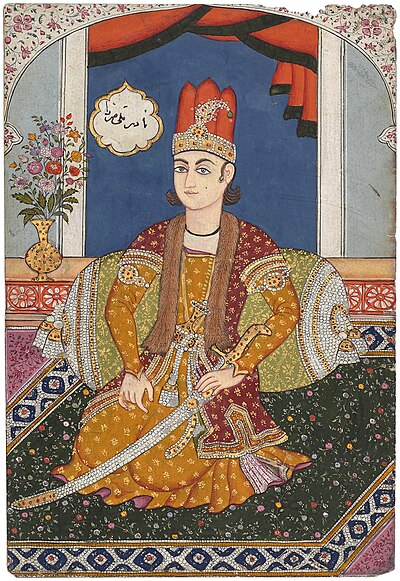

During this period, Iran experienced increased Western diplomatic engagement under Fath Ali Shah. His grandson, Mohammad Shah Qajar, influenced by Russia, unsuccessfully attempted to capture Herat. Naser al-Din Shah Qajar, succeeding Mohammad Shah, was a more successful ruler, founding Iran's first modern hospital.[64]

The Great Persian Famine of 1870–1871 was a catastrophic event, resulting in the death of approximately two million people.[65] This period marked a significant transition in Persian history, leading to the Persian Constitutional Revolution against the Shah in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. Despite challenges, the Shah conceded to a limited constitution in 1906, transforming Persia into a constitutional monarchy and leading to the convening of the first Majlis (parliament) on October 7, 1906.

The discovery of oil in 1908 in Khuzestan by the British intensified foreign interests in Persia, particularly by the British Empire (related to William Knox D'Arcy and the Anglo-Iranian Oil Company, now BP). This period was also marked by the geopolitical rivalry between the United Kingdom and Russia over Persia, known as The Great Game. The Anglo-Russian Convention of 1907 divided Persia into spheres of influence, undermining its national sovereignty.

During World War I, Persia was occupied by British, Ottoman, and Russian forces but remained largely neutral. Post-World War I and the Russian Revolution, Britain attempted to establish a protectorate over Persia, which ultimately failed.

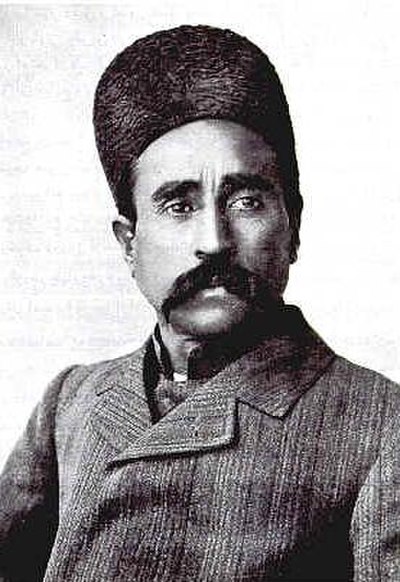

The instability within Persia, highlighted by the Constitutionalist movement of Gilan and the Qajar government's weakening, paved the way for the rise of Reza Khan, later Reza Shah Pahlavi, and the establishment of the Pahlavi dynasty in 1925. A pivotal 1921 military coup, led by Reza Khan of the Persian Cossack Brigade and Seyyed Zia'eddin Tabatabai, was initially aimed at controlling government officials rather than directly overthrowing the Qajar monarchy.[66] Reza Khan's influence grew, and by 1925, after serving as prime minister, he became the first Shah of the Pahlavi dynasty.