The Battle of Geok Tepe in 1881, also known as Denghil-Tepe or Dangil Teppe, was a decisive conflict in the 1880/81 Russian campaign against the Teke tribe of Turkmens, leading to Russian control over most of modern Turkmenistan and nearing the completion of Russia's conquest of Central Asia. The fortress of Geok Tepe, with its substantial mud walls and defenses, was located in the Akhal Oasis, an area supported by agriculture due to irrigation from the Kopet Dagh mountains.

After a failed attempt in 1879, Russia, under Mikhail Skobelev's command, prepared for a renewed offensive. Skobelev opted for a siege strategy over a direct assault, focusing on logistical buildup and slow, methodical advance. By December 1880, Russian forces were positioned near Geok Tepe, with significant numbers of infantry, cavalry, artillery, and modern military technologies including rockets and heliographs.

The siege began in early January 1881, with Russian troops establishing positions and conducting reconnaissance to isolate the fortress and cut off its water supply. Despite several Turkmen sorties, which inflicted casualties but also resulted in heavy losses for the Tekkes, the Russians made steady progress. On January 23, a mine filled with explosives was placed under the fort's walls, leading to a major breach the following day.

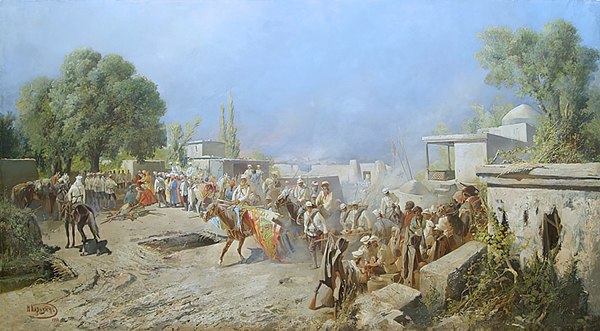

The final assault on January 24 started with a comprehensive artillery barrage, followed by the explosion of the mine, creating a breach through which Russian forces entered the fortress. Despite initial resistance and a smaller breach proving difficult to penetrate, Russian troops managed to secure the fortress by afternoon, with the Tekkes fleeing and pursued by Russian cavalry.

The battle's aftermath was brutal: Russian casualties for January were over a thousand, with significant ammunition expended. Tekke losses were estimated at 20,000. The capture of Ashgabat followed on January 30, marking a strategic victory but at the cost of heavy civilian casualties, leading to Skobelev's removal from command. The battle and subsequent Russian advances solidified their control over the region, with the establishment of Transcaspia as a Russian oblast and the formalization of borders with Persia. The battle is commemorated in Turkmenistan as a national day of mourning and symbol of resistance, reflecting on the heavy toll of the conflict and the enduring impact on Turkmen national identity.