Education in the Soviet Union was guaranteed as a constitutional right to all people provided through state schools and universities. The education system that emerged after the establishment of the Soviet Union in 1922 became internationally renowned for its successes in eradicating illiteracy and cultivating a highly educated population. Its advantages were total access for all citizens and post-education employment. The Soviet Union recognized that the foundation of their system depended upon an educated population and development in the broad fields of engineering, the natural sciences, the life sciences and social sciences, along with basic education.

An important aspect of the early campaign for literacy and education was the policy of "indigenisation" (korenizatsiya). This policy, which lasted essentially from the mid-1920s to the late 1930s, promoted the development and use of non-Russian languages in the government, the media, and education. Intended to counter the historical practices of Russification, it had as another practical goal assuring native-language education as the quickest way to increase educational levels of future generations. A huge network of so-called "national schools" was established by the 1930s, and this network continued to grow in enrollments throughout the Soviet era. Language policy changed over time, perhaps marked first of all in the government's mandating in 1938 the teaching of Russian as a required subject of study in every non-Russian school, and then especially beginning in the latter 1950s a growing conversion of non-Russian schools to Russian as the main medium of instruction. However, an important legacy of the native-language and bilingual education policies over the years was the nurturing of widespread literacy in dozens of languages of indigenous nationalities of the USSR, accompanied by widespread and growing bilingualism in which Russian was said to be the "language of internationality communication."

In 1923 a new school statute and curricula were adopted. Schools were divided into three separate types, designated by the number of years of instruction: "four year", "seven year" and "nine year" schools. Seven and nine-year (secondary) schools were scarce, compared to the "four-year" (primary) schools, making it difficult for the pupils to complete their secondary education. Those who finished seven-year schools had the right to enter Technicums. Only nine-year school led directly to university-level education.

The curriculum was changed radically. Independent subjects, such as reading, writing, arithmetic, the mother tongue, foreign languages, history, geography, literature or science were abolished. Instead school programmes were subdivided into "complex themes", such as "the life and labour of the family in village and town" for the first year or "scientific organisation of labour" for the 7th year of education. Such a system was a complete failure, however, and in 1928 the new programme completely abandoned the complex themes and resumed instruction in individual subjects.

All students were required to take the same standardised classes. This continued until the 1970s when older students began being given time to take elective courses of their own choice in addition to the standard courses. Since 1918 all Soviet schools were co-educational. In 1943, urban schools were separated into boys and girls schools. In 1954 the mixed-sex education system was restored.

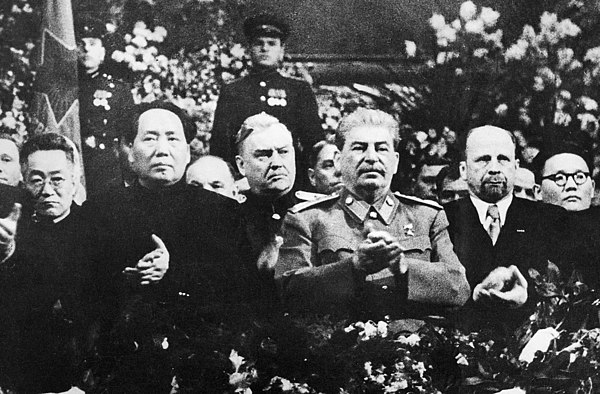

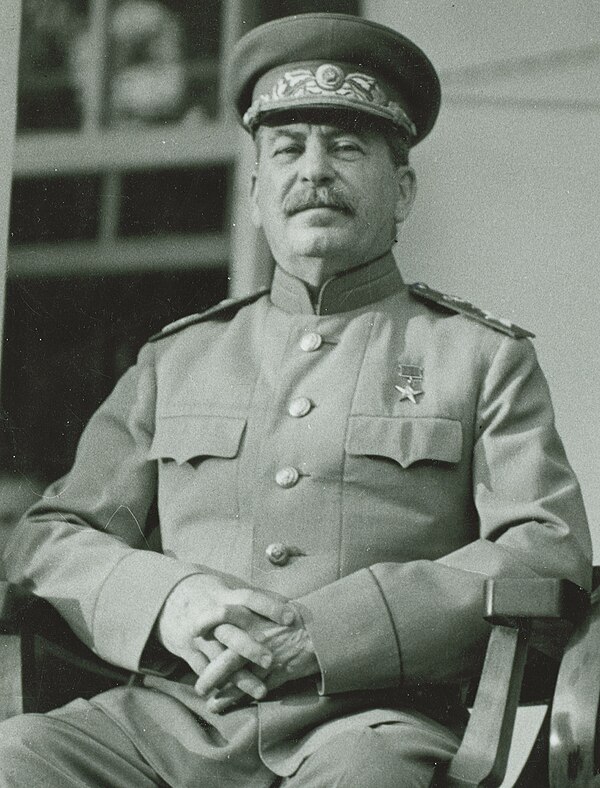

Soviet education in 1930s–1950s was inflexible and suppressive. Research and education, in all subjects but especially in the social sciences, was dominated by Marxist-Leninist ideology and supervised by the CPSU. Such domination led to abolition of whole academic disciplines such as genetics. Scholars were purged as they were proclaimed bourgeois during that period. Most of the abolished branches were rehabilitated later in Soviet history, in the 1960s–1990s (e.g., genetics was in October 1964), although many purged scholars were rehabilitated only in post-Soviet times. In addition, many textbooks - such as history ones - were full of ideology and propaganda, and contained factually inaccurate information (see Soviet historiography). The educational system’s ideological pressure continued, but in the 1980s, the government’s more open policies influenced changes that made the system more flexible . Shortly before the Soviet Union collapsed, schools no longer had to teach subjects from the Marxist-Leninist perspective at all.

Another aspect of the inflexibility was the high rate at which pupils were held back and required to repeat a year of school. In the early 1950s, typically 8–10% of pupils in elementary grades were held back a year. This was partly attributable to the pedagogical style of teachers, and partly to the fact that many of these children had disabilities that impeded their performance. In the latter 1950s, however, the Ministry of Education began to promote the creation of a wide variety of special schools (or "auxiliary schools") for children with physical or mental handicaps. Once those children were taken out of the mainstream (general) schools, and once teachers began to be held accountable for the repeat rates of their pupils, the rates fell sharply. By the mid-1960s the repeat rates in the general primary schools declined to about 2%, and by the late 1970s to less than 1%.

The number of schoolchildren enrolled in special schools grew fivefold between 1960 and 1980. However, the availability of such special schools varied greatly from one republic to another. On a per capita basis, such special schools were most available in the Baltic republics, and least in the Central Asian ones. This difference probably had more to do with the availability of resources than with the relative need for the services by children in the two regions.

In the 1970s and 1980s, approximately 99.7% of Soviet people were literate.