Ottoman Syria, spanning from the early 16th century to the aftermath of World War I, was a period marked by significant political, social, and demographic changes. After the Ottoman Empire conquered the region in 1516, it was integrated into the empire's vast territories, bringing a degree of stability after the turbulent Mamluk period. The Ottomans organized the area into several administrative units, with Damascus emerging as a major center of governance and commerce. The empire's rule introduced new systems of taxation, land tenure, and bureaucracy, significantly impacting the social and economic fabric of the region.

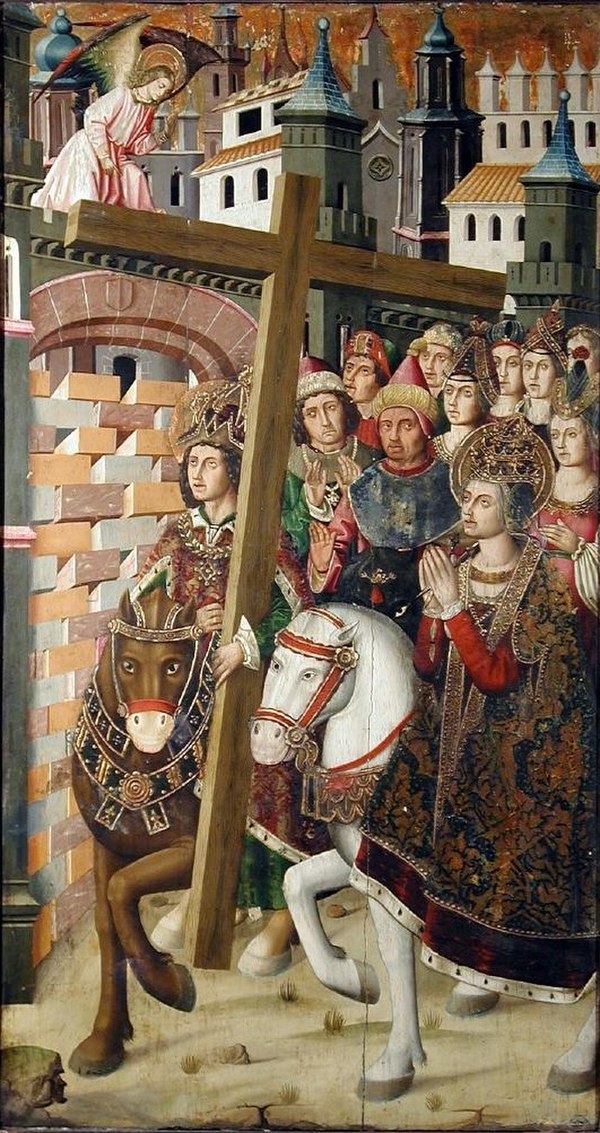

The Ottoman conquest of the region led to the continued immigration of Jews fleeing persecution in Catholic Europe. This trend, which started under Mamluk rule, saw a significant influx of Sephardic Jews, who eventually dominated the Jewish community in the area.[148] In 1558, Selim II's rule, influenced by his Jewish wife Nurbanu Sultan,[149] saw the control of Tiberias given to Doña Gracia Mendes Nasi. She encouraged Jewish refugees to settle there and established a Hebrew printing press in Safed, which became a center for Kabbalah studies.

During the Ottoman era, Syria experienced a diverse demographic landscape. The population was predominantly Muslim, but there were significant Christian and Jewish communities. The empire's relatively tolerant religious policies allowed for a degree of religious freedom, fostering a multicultural society. This period also saw the immigration of various ethnic and religious groups, further enriching the region's cultural tapestry. Cities like Damascus, Aleppo, and Jerusalem became thriving centers of trade, scholarship, and religious activity.

The area experienced turmoil in 1660 due to a Druze power struggle, resulting in the destruction of Safed and Tiberias.[150] The 18th and 19th centuries witnessed the rise of local powers challenging Ottoman authority. In the late 18th century, Sheikh Zahir al-Umar's independent Emirate in the Galilee challenged Ottoman rule, reflecting the weakening central authority of the Ottoman Empire.[151] These regional leaders often embarked on projects to develop infrastructure, agriculture, and trade, leaving a lasting impact on the region's economy and urban landscape. Napoleon's brief occupation in 1799 included plans for a Jewish state, abandoned after his defeat at Acre.[152] In 1831, Muhammad Ali of Egypt, an Ottoman ruler who left the Empire and tried to modernize Egypt, conquered Ottoman Syria and imposed conscription, leading to the Arab revolt.[153]

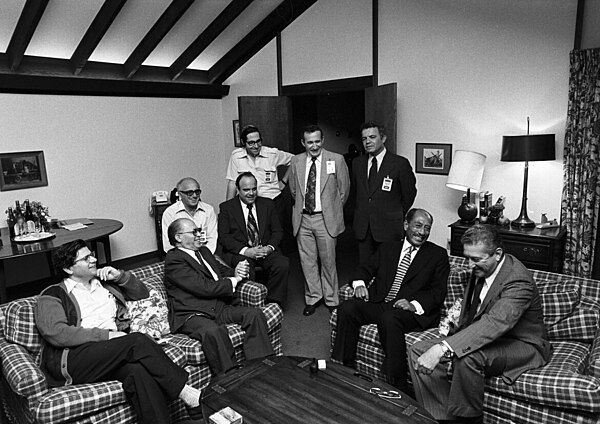

The 19th century brought European economic and political influence to Ottoman Syria, alongside internal reforms under the Tanzimat period. These reforms aimed to modernize the empire and included the introduction of new legal and administrative systems, educational reforms, and an emphasis on equal rights for all citizens. However, these changes also led to social unrest and nationalistic movements among various ethnic and religious groups, laying the groundwork for the complex political dynamics of the 20th century. An agreement in 1839 between Moses Montefiore and Muhammed Pasha for Jewish villages in Damascus Eyalet remained unimplemented due to Egyptian withdrawal in 1840.[154] By 1896, Jews formed the majority in Jerusalem,[[155] but the overall population in Palestine was 88% Muslim and 9% Christian.[156]

The First Aliyah, from 1882 to 1903, saw about 35,000 Jews immigrate to Palestine, mainly from the Russian Empire due to increasing persecution.[157] Russian Jews established agricultural settlements like Petah Tikva and Rishon LeZion, supported by Baron Rothschild.Many early migrants could not find work and left, but despite the problems, more settlements arose and the community grew. After the Ottoman conquest of Yemen in 1881, a large number of Yemenite Jews also emigrated to Palestine, often driven by Messianism.[158] In 1896, Theodor Herzl's "Der Judenstaat" proposed a Jewish state as a solution to antisemitism, leading to the founding of the World Zionist Organization in 1897.[159]

The Second Aliyah, from 1904 to 1914, brought around 40,000 Jews to the region, with the World Zionist Organization establishing a structured settlement policy.[160] In 1909 residents of Jaffa bought land outside the city walls and built the first entirely Hebrew-speaking town, Ahuzat Bayit (later renamed Tel Aviv).[161]

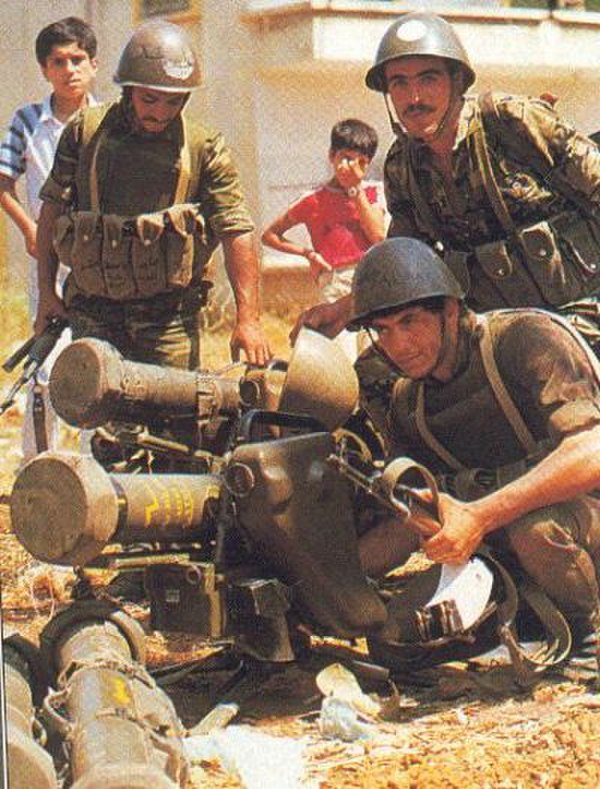

During World War I, Jews mainly supported Germany against Russia.[162] The British, seeking Jewish support, were influenced by perceptions of Jewish influence and aimed to secure American Jewish backing. British sympathy for Zionism, including from Prime Minister Lloyd George, led to policies favoring Jewish interests.[163] Over 14,000 Jews were expelled from Jaffa by the Ottomans between 1914 and 1915, and a general expulsion in 1917 affected all residents of Jaffa and Tel Aviv until the British conquest in 1918.[164]

The final years of Ottoman rule in Syria were marked by the turmoil of World War I. The empire's alignment with the Central Powers and the subsequent Arab Revolt, supported by the British, significantly weakened Ottoman control. Post-war, the Sykes-Picot Agreement and the Treaty of Sèvres led to the partitioning of the Ottoman Empire's Arab provinces, resulting in the end of Ottoman rule in Syria. Palestine was governed under martial law by the British, French, and Arab Occupied Enemy Territory Administration until the mandate's establishment in 1920.