History of the United States

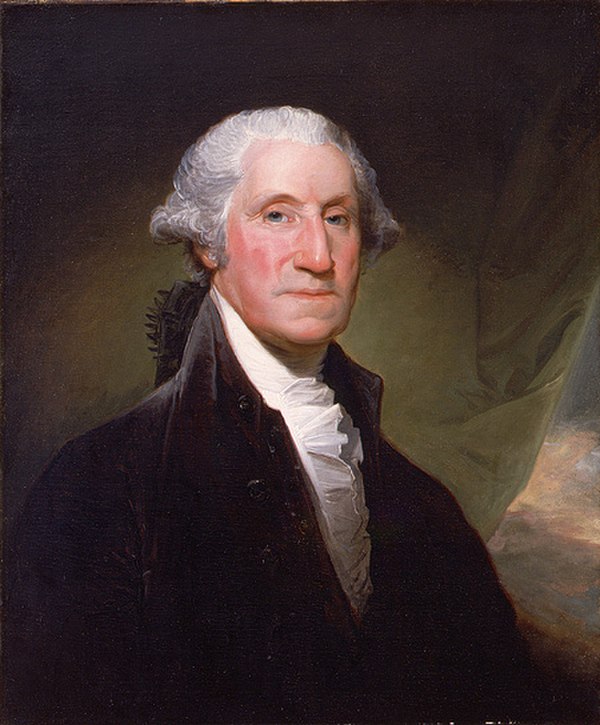

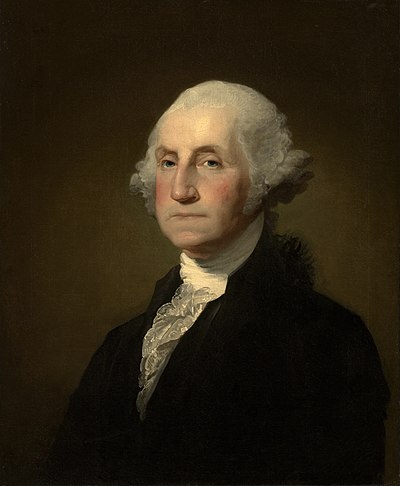

The history of the United States begins with the arrival of Indigenous peoples around 15,000 BCE, followed by European colonization starting in the late 15th century. Key events that shaped the nation include the American Revolution, which began as a response to British taxation without representation and culminated in the Declaration of Independence in 1776. The new nation struggled initially under the Articles of Confederation but found stability with the adoption of the U.S. Constitution in 1789 and the Bill of Rights in 1791, establishing a strong central government led initially by President George Washington.

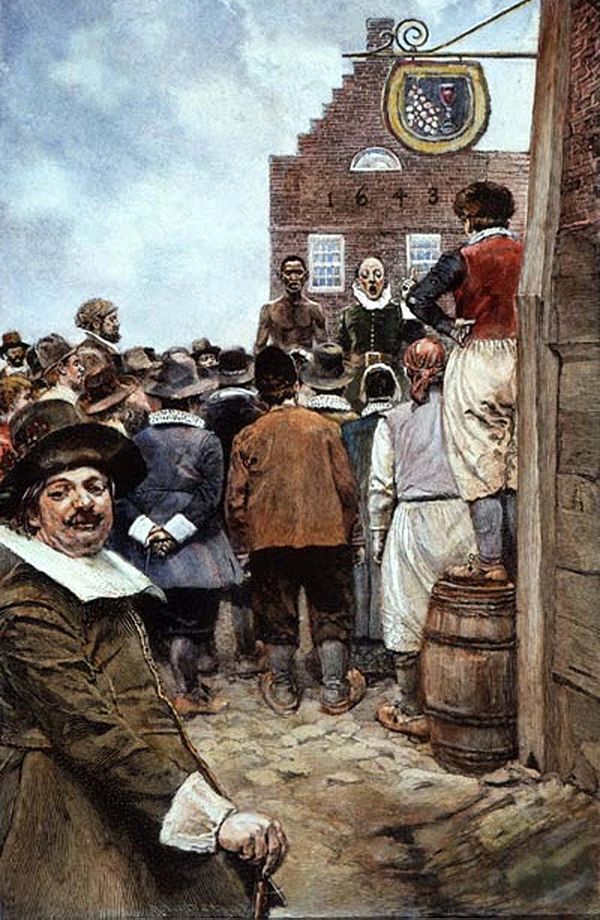

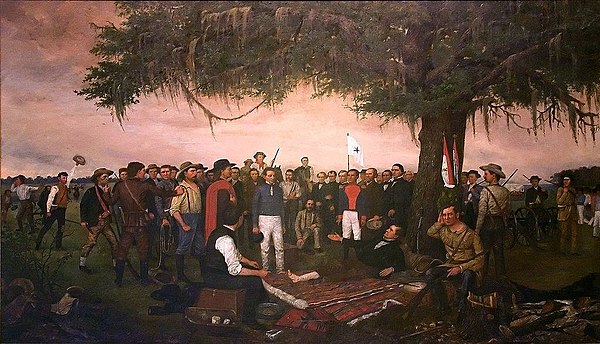

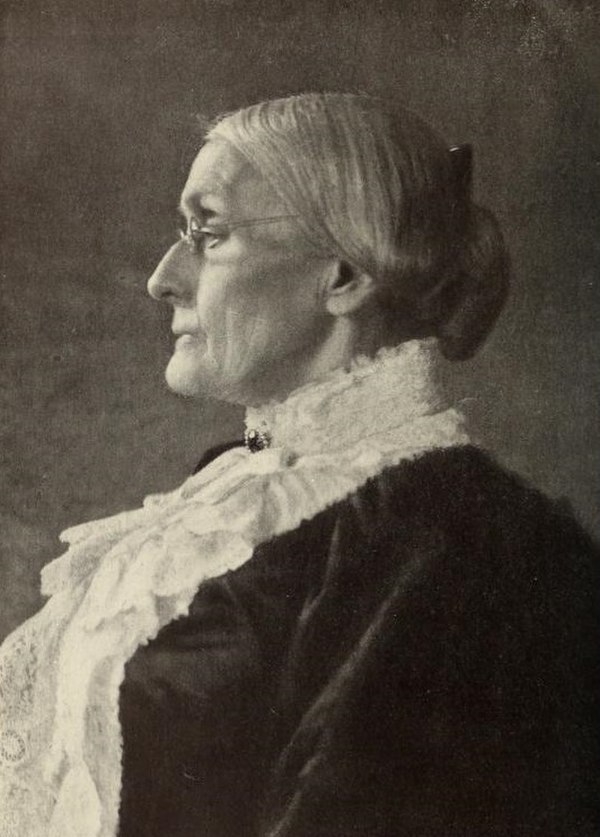

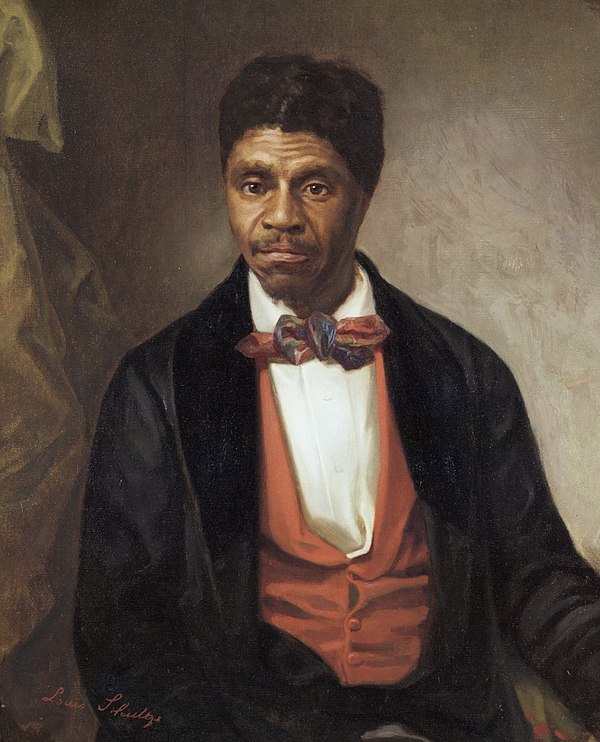

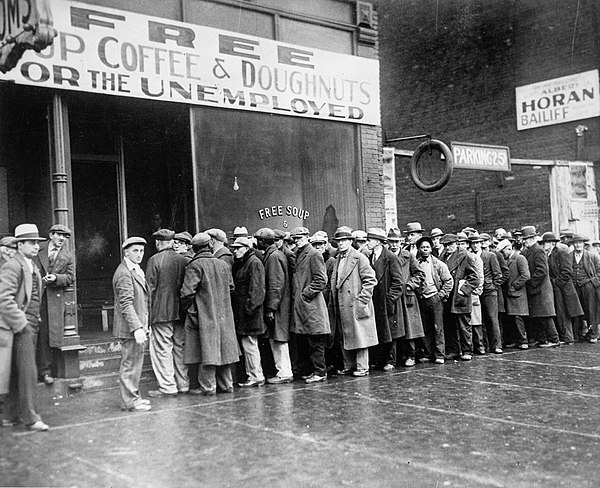

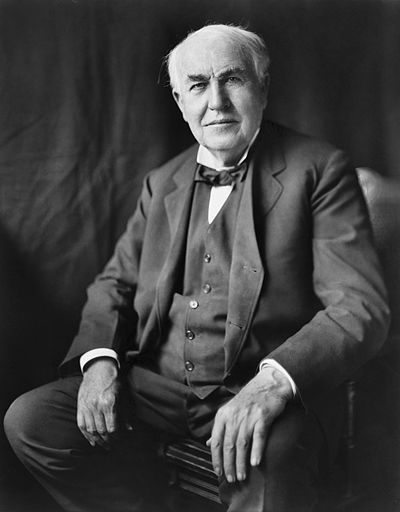

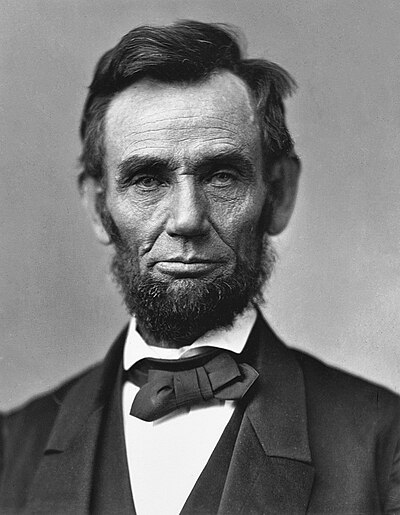

Westward expansion defined the 19th century, fueled by the notion of manifest destiny. This era was also marked by the divisive issue of slavery, leading to the Civil War in 1861 following the election of President Abraham Lincoln. The defeat of the Confederacy in 1865 resulted in the abolition of slavery, and the Reconstruction era extended legal and voting rights to freed male slaves. However, the Jim Crow era that followed disenfranchised many African Americans until the civil rights movement of the 1960s. During this period, the U.S. also emerged as an industrial power, experiencing social and political reforms including women's suffrage and the New Deal, which helped define modern American liberalism.[1]

The U.S. solidified its role as a global superpower in the 20th century, particularly during and after World War II. The Cold War era saw the U.S. and the Soviet Union as rival superpowers engaged in an arms race and ideological battles. The civil rights movement of the 1960s achieved significant social reforms, particularly for African Americans. The end of the Cold War in 1991 left the U.S. as the world's sole superpower, and recent foreign policy has often focused on conflicts in the Middle East, especially following the September 11 attacks.