History of Saudi Arabia

Saudi Arabia's history as a nation state began in 1727 with the rise of the Al Saud dynasty and the formation of the Emirate of Diriyah . This area, known for its ancient cultures and civilizations, is significant for early human activity traces . Islam, emerging in the 7th century, saw rapid territorial expansion post-Muhammad's death in 632, leading to the establishment of several influential Arab dynasties.

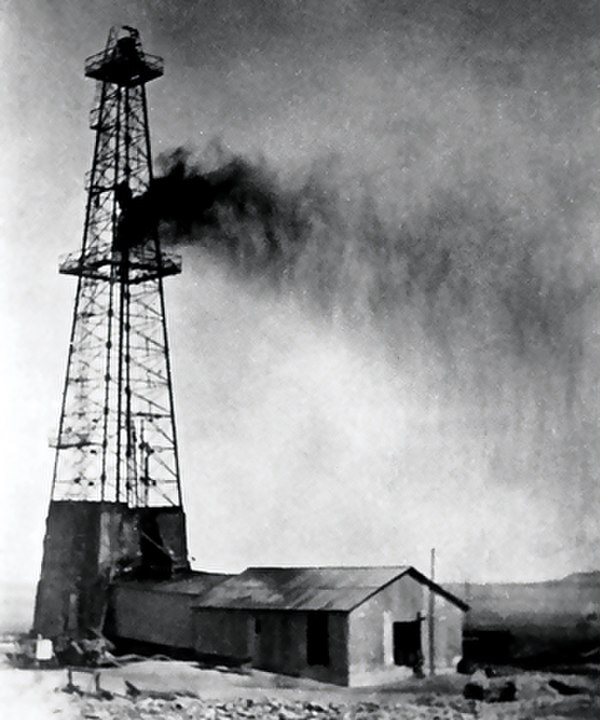

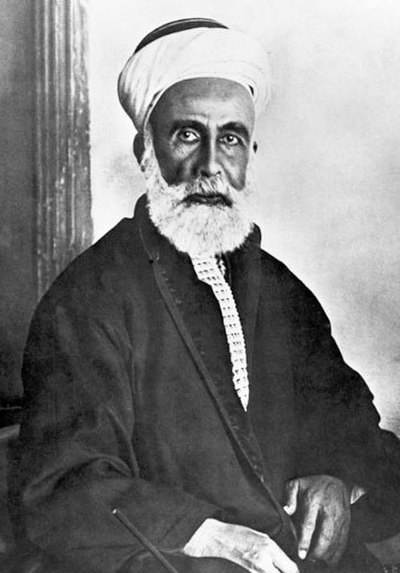

Four regions—Hejaz, Najd, Eastern Arabia, and Southern Arabia—formed modern-day Saudi Arabia, unified in 1932 by Abdulaziz bin Abdul Rahman (Ibn Saud). He began his conquests in 1902, establishing Saudi Arabia as an absolute monarchy. The discovery of petroleum in 1938 transformed it into a major oil producer and exporter.

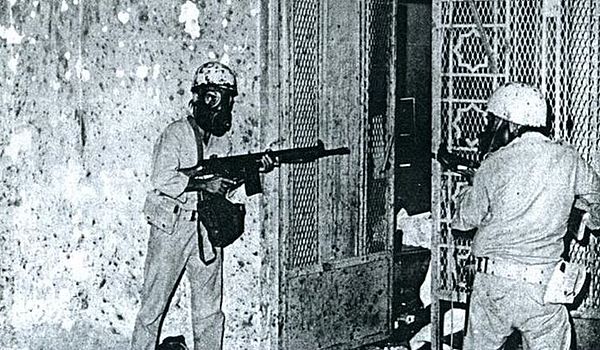

Abdulaziz's rule (1902–1953) was followed by successive reigns of his sons, each contributing to Saudi Arabia's evolving political and economic landscape. Saud faced royal opposition; Faisal (1964–1975) led during a period of oil-fueled growth; Khalid witnessed the 1979 Grand Mosque seizure; Fahd (1982–2005) saw increased internal tensions and the 1991 Gulf War alignment; Abdullah (2005–2015) initiated moderate reforms; and Salman (since 2015) reorganized government power, largely into the hands of his son, Mohammed bin Salman, who has been influential in legal, social, and economic reforms and the Yemeni Civil War intervention.