History of Korea

The history of Korea traces back to the Lower Paleolithic era, with the earliest known human activity on the Korean Peninsula and in Manchuria occurring roughly half a million years ago.[1] The Neolithic period began after 6000 BCE, highlighted by the advent of pottery around 8000 BCE. By 2000 BCE, the Bronze Age had commenced, followed by the Iron Age around 700 BCE.[2] Interestingly, according to The History of Korea, the Paleolithic people are not the direct ancestors of the present Korean people, but their direct ancestors are estimated to be the Neolithic People of about 2000 BCE.[3]

The mythical Samguk Yusa recounts the establishment of the Gojoseon kingdom in northern Korea and southern Manchuria.[4] While the exact origins of Gojoseon remain speculative, archaeological evidence confirms its existence on the Korean Peninsula and Manchuria by at least the 4th century BCE. The Jin state in southern Korea emerged by the 3rd century BCE. By the end of the 2nd century BCE, Wiman Joseon replaced Gija Joseon and subsequently succumbed to China's Han dynasty. This led to the Proto–Three Kingdoms period, a tumultuous era marked by constant warfare.

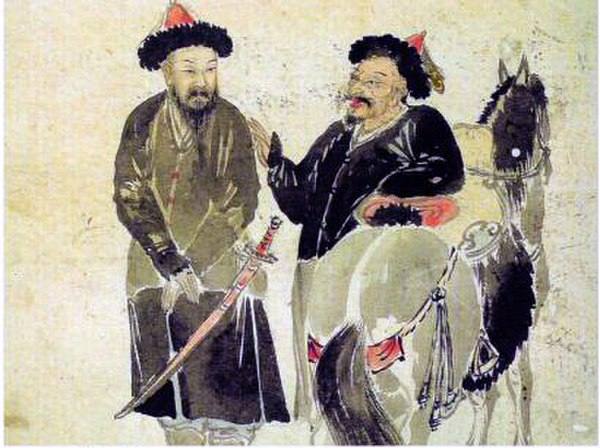

The Three Kingdoms of Korea, comprising Goguryeo, Baekje, and Silla, began to dominate the peninsula and Manchuria from the 1st century BCE. Silla's unification in 676 CE marked the end of this tripartite rule. Soon after, in 698, King Go founded Balhae in former Goguryeo territories, ushering in the Northern and Southern States period (698–926) where Balhae and Silla coexisted. The late 9th century saw the disintegration of Silla into the Later Three Kingdoms (892–936), which eventually unified under Wang Geon's Goryeo dynasty. Concurrently, Balhae fell to the Khitan-led Liao dynasty, with the remnants, including the last crown prince, integrating into Goryeo.[5] The Goryeo era was marked by codification of laws, a structured civil service system, and a flourishing Buddhist-influenced culture. However, by the 13th century, the Mongol invasions had brought Goryeo under the influence of the Mongol Empire and China's Yuan dynasty.[6]

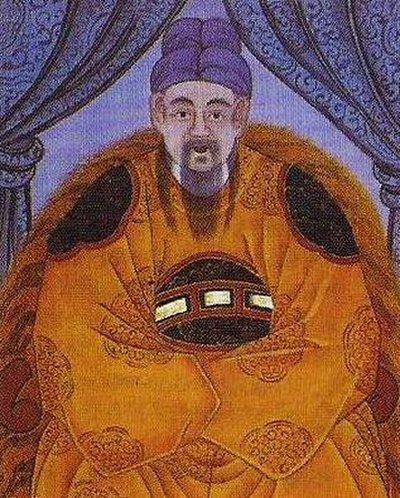

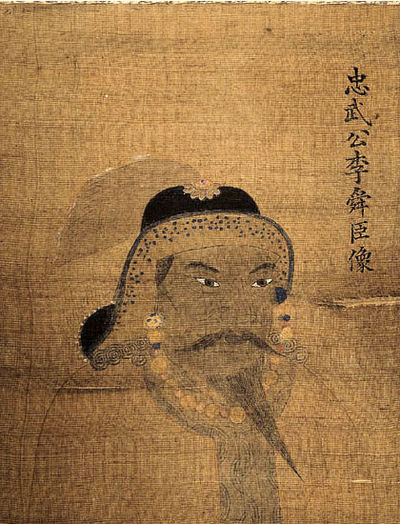

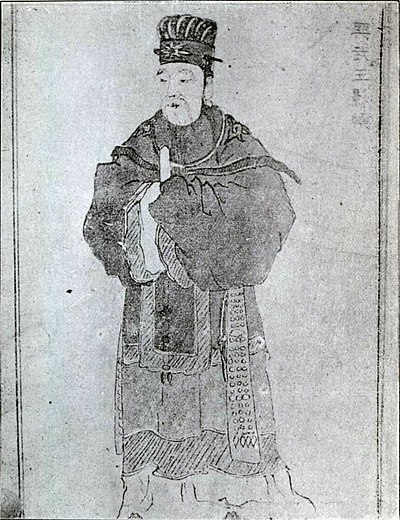

General Yi Seong-gye established the Joseon dynasty in 1392, following a successful coup against the Goryeo dynasty.[7] The Joseon era witnessed significant advancements, especially under King Sejong the Great (1418–1450), who introduced numerous reforms and created Hangul, the Korean alphabet. However, the late 16th and early 17th centuries were marred by foreign invasions and internal discord, notably the Japanese invasions of Korea. Despite successfully repelling these invasions with the help of Ming China, both nations suffered extensive damages. Subsequently, the Joseon dynasty became increasingly isolationist, culminating in the 19th century when Korea, reluctant to modernize, was coerced into signing unequal treaties with European powers. This period of decline eventually led to the establishment of the Korean Empire (1897–1910), a brief era of rapid modernization and social reform. Nevertheless, by 1910, Korea had become a Japanese colony, a status it would maintain until 1945.

Korean resistance against Japanese rule peaked with the widespread March 1st Movement of 1919. Post-World War II, in 1945, the Allies partitioned Korea into a northern region, overseen by the Soviet Union, and a southern region under United States supervision. This division solidified in 1948 with the establishment of North and South Korea. The Korean War, initiated by North Korea's Kim Il Sung in 1950, sought to reunify the peninsula under Communist governance. Despite ending in a 1953 cease-fire, the war's ramifications persist to this day. South Korea underwent significant democratization and economic growth, achieving a status comparable to developed Western nations. Conversely, North Korea, under the Kim family's totalitarian rule, has remained economically challenged and reliant on foreign aid.