On the night of 1 November 1841, a group of Afghan chiefs met at the Kabul house of one of their number to plan the uprising, which began in the morning of the next day. In a flammable situation, the spark was provided unintentionally by the East India Company's second political officer, Sir Alexander 'Sekundar' Burnes. A Kashmiri slave girl who belonged to a Pashtun chief Abdullah Khan Achakzai living in Kabul ran away to Burne's house. When Ackakzai sent his retainers to retrieve her, it was discovered that Burnes had taken the slave girl to his bed, and he had one of Azkakzai's men beaten. A secret jirga (council) of Pashtun chiefs was held to discuss this violation of pashtunwali, where Ackakzai holding a Koran in one hand stated: "Now we are justified in throwing this English yoke; they stretch the hand of tyranny to dishonor private citizens great and small: fucking a slave girl isn't worth the ritual bath that follows it: but we have to put a stop right here and now, otherwise these English will ride the donkey of their desires into the field of stupidity, to the point of having all of us arrested and deported to a foreign field". At the end of his speech, all of the chiefs shouted "Jihad". November 2, 1841 actually fell on 17 Ramadan which was the anniversary date for the battle of Badr. The Afghans decided to strike on this date for reasons of the blessings associated with this auspicious date of 17 Ramadan. The call to jihad was given on the morning of 2 November from the Pul-i-khisti mosque in Kabul

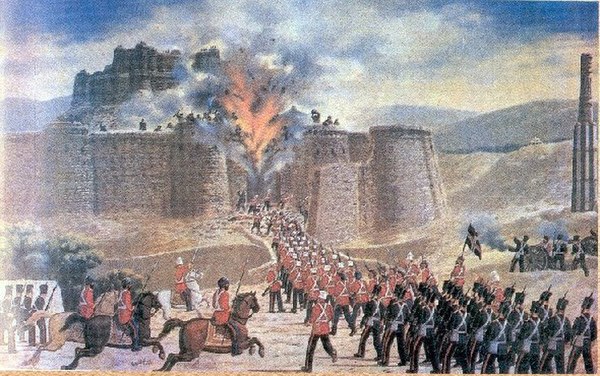

That same day, a mob "thirsting for blood" appeared outside of the house of the East India Company's second political officer, Sir Alexander 'Sekundar' Burnes, where Burnes ordered his sepoy guards not to fire while he stood outside haranguing the mob in Pashto, attempting unconvincingly to persuade the assembled men that he did not bed their daughters and sisters. The mob smashed in to Burnes's house, where he, his brother Charles, their wives and children, several aides and the sepoys were all torn to pieces. The British forces took no action in response despite being only five minutes away, which encouraged further revolt. The only person who took action that day was Shuja who ordered out one of his regiments from the Bala Hissar commanded by a Scots mercenary named Campbell to crush the riot, but the old city of Kabul with its narrow, twisting streets favored the defenders, with Campbell's men coming under fire from rebels in the houses above. After losing about 200 men killed, Campbell retreated back to the Bala Hissar. The British situation soon deteriorated when Afghans stormed the poorly defended supply fort inside Kabul on 9 November.

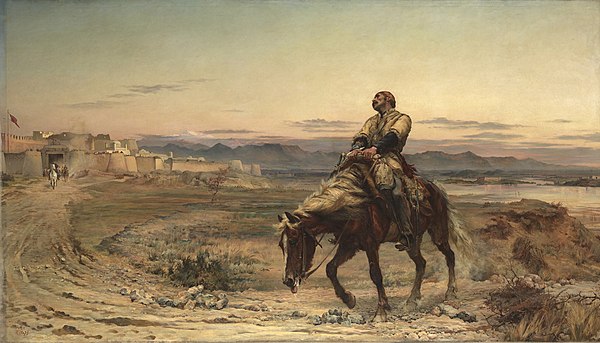

In the following weeks, the British commanders tried to negotiate with Akbar Khan. Macnaghten secretly offered to make Akbar Afghanistan's vizier in exchange for allowing the British to stay, while simultaneously disbursing large sums of money to have him assassinated, which was reported to Akbar Khan. A meeting for direct negotiations between Macnaghten and Akbar was held near the cantonment on 23 December, but Macnaghten and the three officers accompanying him were seized and slain by Akbar Khan. Macnaghten's body was dragged through the streets of Kabul and displayed in the bazaar. Elphinstone had partly lost command of his troops already and his authority was badly damaged.