History of Judaism

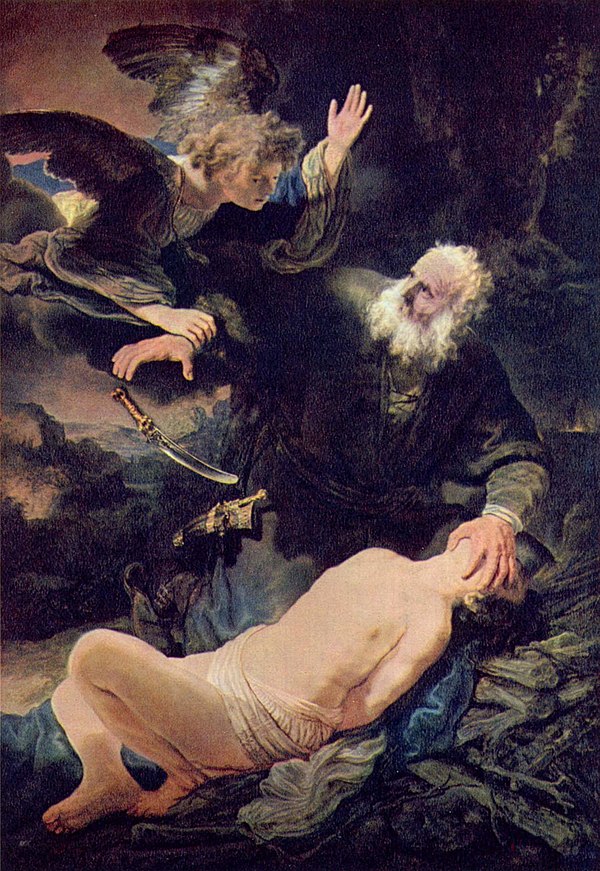

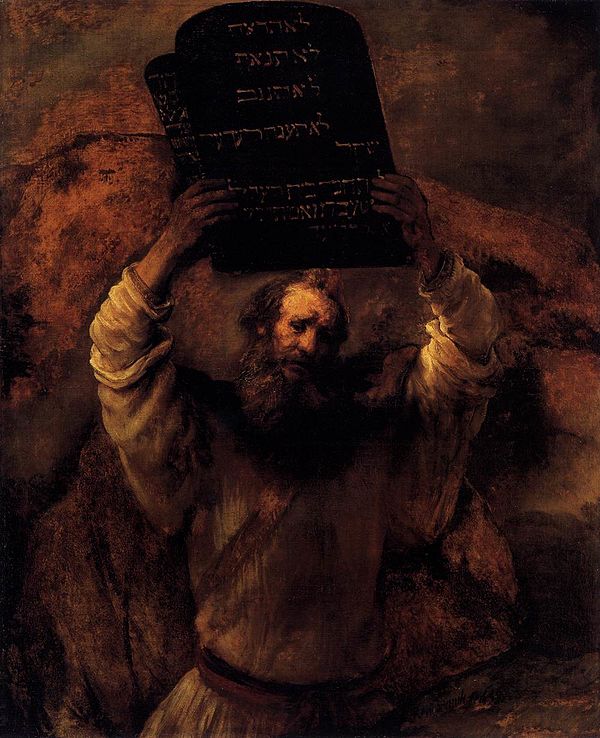

Judaism is an Abrahamic, monotheistic, and ethnic religion comprising the collective religious, cultural, and legal tradition and civilization of the Jewish people. It has its roots as an organized religion in the Middle East during the Bronze Age. Some scholars argue that modern Judaism evolved from Yahwism, the religion of ancient Israel and Judah, by the late 6th century BCE, and is thus considered to be one of the oldest monotheistic religions. Judaism is considered by religious Jews to be the expression of the covenant that God established with the Israelites, their ancestors. It encompasses a wide body of texts, practices, theological positions, and forms of organization.

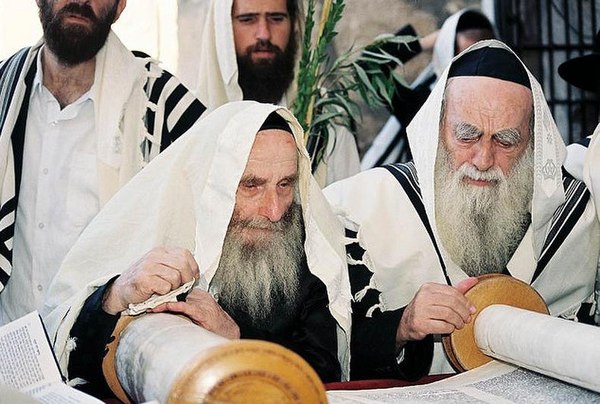

The Torah, as it is commonly understood by Jews, is part of the larger text known as the Tanakh. The Tanakh is also known to secular scholars of religion as the Hebrew Bible, and to Christians as the "Old Testament". The Torah's supplemental oral tradition is represented by later texts such as the Midrash and the Talmud. The Hebrew word torah can mean "teaching", "law", or "instruction", although "Torah" can also be used as a general term that refers to any Jewish text that expands or elaborates on the original Five Books of Moses. Representing the core of the Jewish spiritual and religious tradition, the Torah is a term and a set of teachings that are explicitly self-positioned as encompassing at least seventy, and potentially infinite, facets and interpretations. Judaism's texts, traditions, and values strongly influenced later Abrahamic religions, including Christianity and Islam. Hebraism, like Hellenism, played a seminal role in the formation of Western civilization through its impact as a core background element of Early Christianity.