History of Republic of India

The Republic of India's history began on 15 August 1947, becoming an independent nation within the British Commonwealth. British administration, starting in 1858, unified the subcontinent politically and economically. In 1947, the end of British rule led to the partition of the subcontinent into India and Pakistan, based on religious demographics: India had a Hindu majority, while Pakistan was predominantly Muslim. This partition caused the migration of over 10 million people and approximately one million deaths.

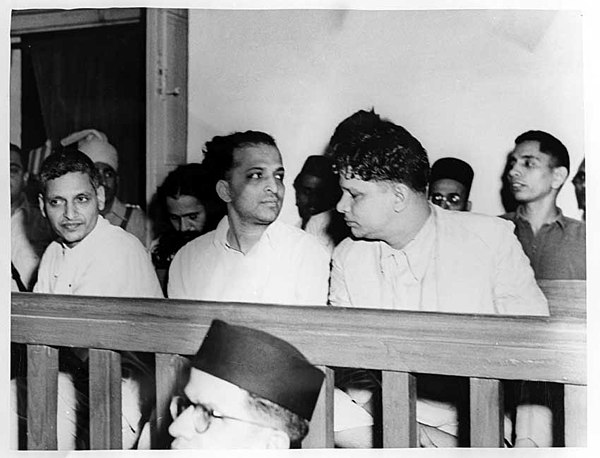

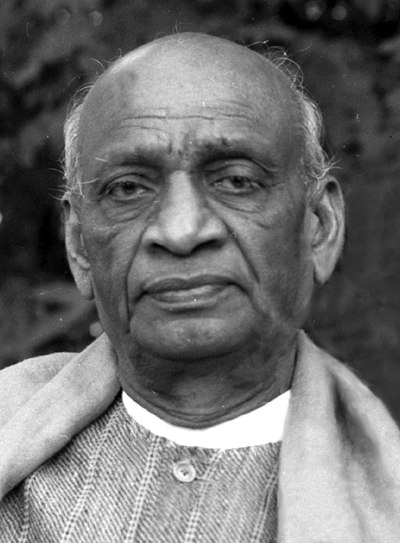

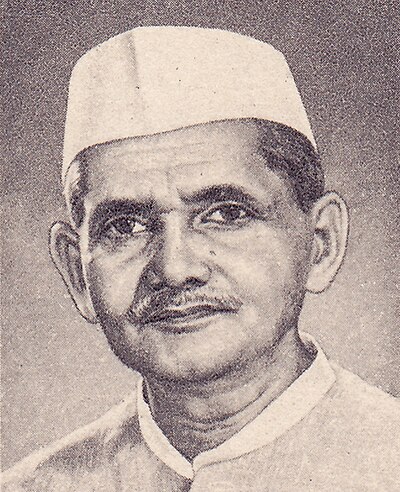

Jawaharlal Nehru, a leader of the Indian National Congress, became India's first Prime Minister. Mahatma Gandhi, a key figure in the independence movement, did not take any official role. In 1950, India adopted a constitution establishing a democratic republic with a parliamentary system at both federal and state levels. This democracy, unique among new states at the time, has persisted.

India has faced challenges like religious violence, naxalism, terrorism, and regional separatist insurgencies. It has engaged in territorial disputes with China, leading to conflicts in 1962 and 1967, and with Pakistan, resulting in wars in 1947, 1965, 1971, and 1999. During the Cold War, India remained neutral and was a leader in the Non-Aligned Movement, though it formed a loose alliance with the Soviet Union in 1971.

India, a nuclear-weapon state, conducted its first nuclear test in 1974 and further tests in 1998. From the 1950s to the 1980s, India's economy was marked by socialist policies, extensive regulation, and public ownership, which led to corruption and slow growth. Since 1991, India has implemented economic liberalization. Today, it is the third largest and one of the fastest-growing economies globally.

Initially struggling, the Republic of India has now become a major G20 economy, sometimes regarded as a great power and potential superpower, due to its large economy, military, and population.