History of China

The history of China is expansive, dating back several millennia and comprising a wide geographical scope. It began in key river valleys like the Yellow, Yangtze, and Pearl rivers where classical Chinese civilization first emerged. The traditional lens through which Chinese history is viewed is the dynastic cycle, with each dynasty contributing to a thread of continuity that stretches back thousands of years. The Neolithic period saw the rise of early societies along these rivers, with the Erlitou culture and Xia dynasty being among the earliest. Writing in China dates back to roughly 1250 BCE, as seen in oracle bones and bronze inscriptions, making China one of the few places where writing was independently invented.

China was first united as an imperial state under Qin Shi Huang in 221 BCE, marking the start of the classical age with the Han dynasty (206 BCE - CE 220). The Han era was significant for several reasons; it standardized weights, measures, and law across the country. It also saw the official adoption of Confucianism, the creation of the earliest core texts, and significant technological advancements that were on par with the Roman Empire at the time. During this era, China also reached some of its furthest geographical extents.

The Sui dynasty in the late 6th century briefly united China before giving way to the Tang dynasty (608–907), considered another golden age. The Tang period was marked by significant developments in science, technology, poetry, and economics. Buddhism and orthodox Confucianism were also highly influential during this time. The succeeding Song dynasty (960–1279) represented the peak of Chinese cosmopolitan development, with the introduction of mechanical printing and significant scientific advancements. The Song era also solidified the integration of Confucianism and Taoism into Neo-Confucianism.

By the 13th century, the Mongol Empire had conquered China, leading to the establishment of the Yuan dynasty in 1271. Contact with Europe began to increase. The Ming dynasty (1368–1644) that followed had its own achievements, including global exploration and public works projects like the restoration of the Grand Canal and Great Wall. The Qing dynasty succeeded the Ming and marked the largest territorial extent of imperial China, but also began a period of conflict with European powers, leading to the Opium Wars and unequal treaties.

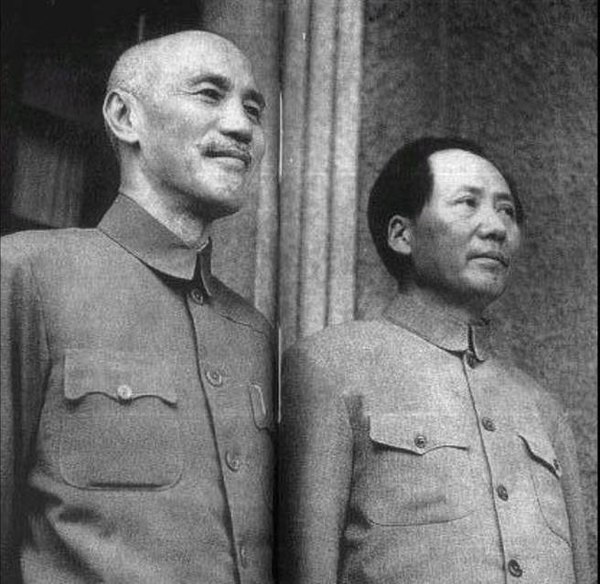

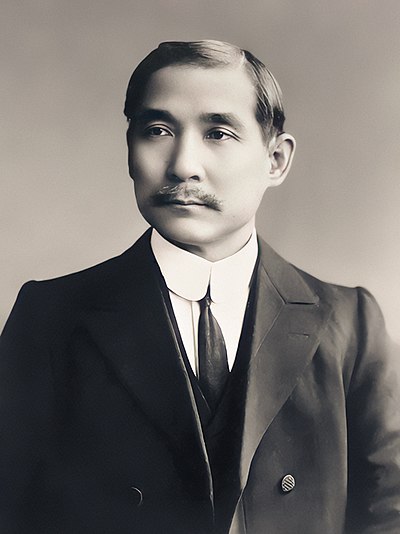

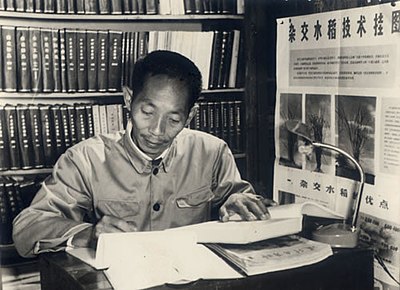

Modern China emerged from the upheavals of the 20th century, starting with the 1911 Xinhai Revolution that led to the Republic of China. A civil war between Nationalists and Communists followed, compounded by an invasion by Japan. The Communist victory in 1949 led to the establishment of the People's Republic of China, with Taiwan continuing as the Republic of China. Both claim to be the legitimate government of China. After the death of Mao Zedong, economic reforms initiated by Deng Xiaoping led to rapid economic growth. Today, China is one of the world's major economies, and as of 2023, it became the second most populous country, surpassed only by India.