Balkan Wars

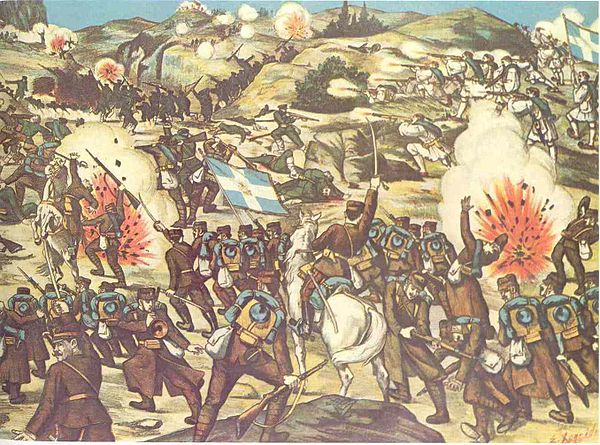

The Balkan Wars refers to a series of two conflicts that took place in the Balkan states in 1912 and 1913. In the First Balkan War, the four Balkan states of Greece, Serbia, Montenegro and Bulgaria declared war upon the Ottoman Empire and defeated it, in the process stripping the Ottomans of its European provinces, leaving only Eastern Thrace under the Ottoman Empire's control. In the Second Balkan War, Bulgaria fought against the other four original combatants of the first war. It also faced an attack from Romania from the north. The Ottoman Empire lost the bulk of its territory in Europe. Although not involved as a combatant, Austria-Hungary became relatively weaker as a much enlarged Serbia pushed for union of the South Slavic peoples.[1] The war set the stage for the Balkan crisis of 1914 and thus served as a "prelude to the First World War".[2]

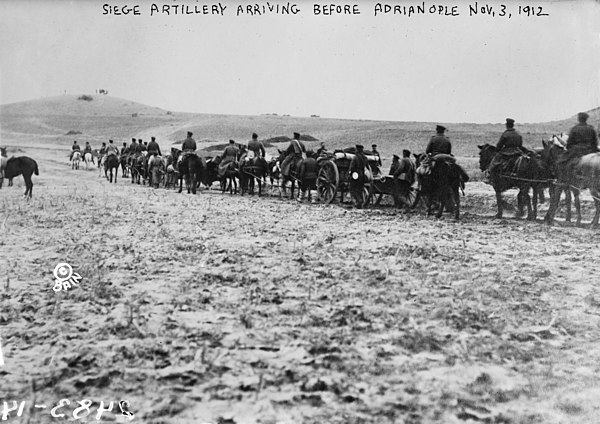

By the early 20th century, Bulgaria, Greece, Montenegro and Serbia had achieved independence from the Ottoman Empire, but large elements of their ethnic populations remained under Ottoman rule. In 1912, these countries formed the Balkan League. The First Balkan War began on 8 October 1912, when the League member states attacked the Ottoman Empire, and ended eight months later with the signing of the Treaty of London on 30 May 1913. The Second Balkan War began on 16 June 1913, when Bulgaria, dissatisfied with its loss of Macedonia, attacked its former Balkan League allies. The combined forces of Serbian and Greek armies, with their superior numbers repelled the Bulgarian offensive and counter-attacked Bulgaria by invading it from the west and the south. Romania, having taken no part in the conflict, had intact armies to strike with and invaded Bulgaria from the north in violation of a peace treaty between the two states. The Ottoman Empire also attacked Bulgaria and advanced in Thrace regaining Adrianople. In the resulting Treaty of Bucharest, Bulgaria managed to regain most of the territories it had gained in the First Balkan War. However, it was forced to cede the ex-Ottoman south part of Dobruja province to Romania.[3]