Mamluk Sultanate

The Mamluk Sultanate was a state that ruled Egypt, the Levant and the Hejaz (western Arabia) in the mid-13th–early 16th centuries. It was ruled by a military caste of mamluks (manumitted slave soldiers) at the head of which was the sultan. The Abbasid caliphs were the nominal sovereigns (figureheads). The sultanate was established with the overthrow of the Ayyubid dynasty in Egypt in 1250 and was conquered by the Ottoman Empire in 1517.

Mamluk history is generally divided into the Turkic or Bahri period (1250–1382) and the Circassian or Burji period (1382–1517), called after the predominant ethnicity or corps of the ruling Mamluks during these respective eras.

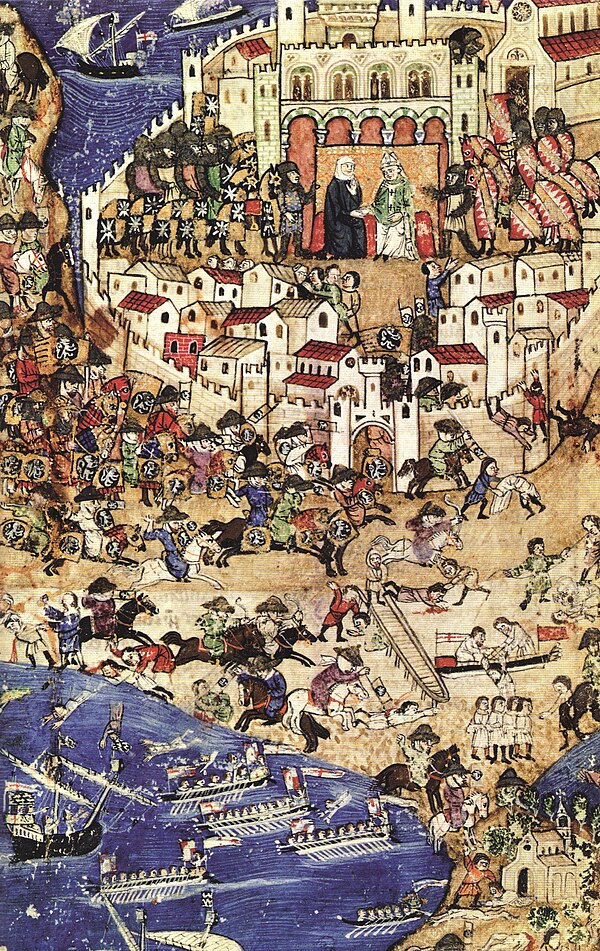

The first rulers of the sultanate hailed from the mamluk regiments of the Ayyubid sultan as-Salih Ayyub, usurping power from his successor in 1250. The Mamluks under Sultan Qutuz and Baybars routed the Mongols in 1260, halting their southward expansion. They then conquered or gained suzerainty over the Ayyubids' Syrian principalities. By the end of the 13th century, they conquered the Crusader states, expanded into Makuria (Nubia), Cyrenaica, the Hejaz and southern Anatolia. The sultanate then experienced a long period of stability and prosperity during the third reign of an-Nasir Muhammad, before giving way to the internal strife characterizing the succession of his sons, when real power was held by senior emirs.