History of Germany

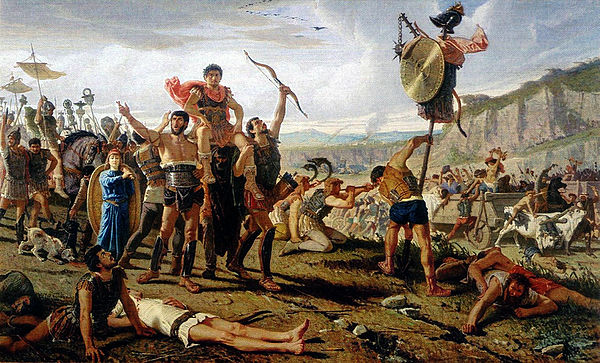

The concept of Germany as a distinct region in Central Europe can be traced to Julius Caesar, who referred to the unconquered area east of the Rhine as Germania, thus distinguishing it from Gaul (France). Following the Fall of the Western Roman Empire, the Franks conquered the other West Germanic tribes. When the Frankish Empire was divided among Charles the Great's heirs in 843, the eastern part became East Francia. In 962, Otto I became the first Holy Roman Emperor of the Holy Roman Empire, the medieval German state.

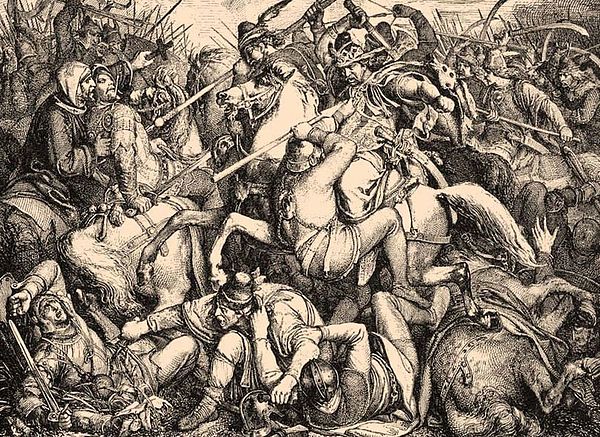

The period of the High Middle Ages saw several important developments within the German-speaking areas of Europe. The first was the establishment of the trading conglomerate known as the Hanseatic League, which was dominated by a number of German port cities along the Baltic and North Sea coasts. The second was the growth of a crusading element within German christendom. This led to the establishment of the State of the Teutonic Order, established along the Baltic coast of what is today Estonia, Latvia, and Lithuania.

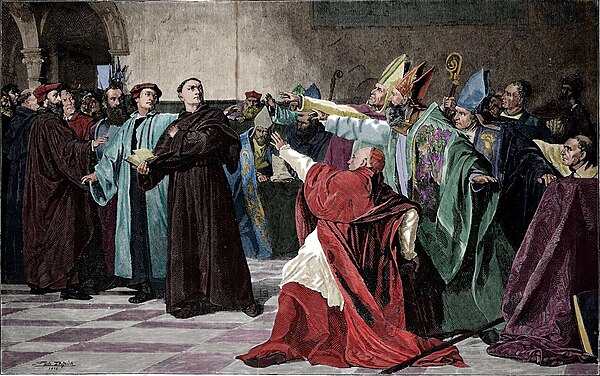

In the Late Middle Ages, the regional dukes, princes, and bishops gained power at the expense of the emperors. Martin Luther led the Protestant Reformation within the Catholic Church after 1517, as the northern and eastern states became Protestant, while most of the southern and western states remained Catholic. The two parts of the Holy Roman Empire clashed in the Thirty Years' War (1618–1648). The estates of the Holy Roman Empire attained a high extent of autonomy in the Peace of Westphalia, some of them being capable of their own foreign policies or controlling land outside of the Empire, the most important being Austria, Prussia, Bavaria and Saxony. With the French Revolution and the Napoleonic Wars from 1803 to 1815, feudalism fell away by reforms and the dissolution of the Holy Roman Empire. Thereafter liberalism and nationalism clashed with reaction. The Industrial Revolution modernized the German economy, led to the rapid growth of cities and the emergence of the socialist movement in Germany. Prussia, with its capital Berlin, grew in power. The unification of Germany was achieved under the leadership of the Chancellor Otto von Bismarck with the formation of the German Empire in 1871.

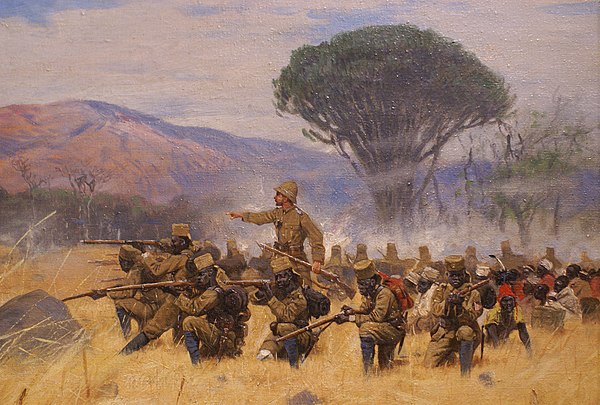

By 1900, Germany was the dominant power on the European continent and its rapidly expanding industry had surpassed Britain's while provoking it in a naval arms race. Since Austria-Hungary declared war on Serbia, Germany had led the Central Powers in World War I (1914–1918) against the Allied Powers. Defeated and partly occupied, Germany was forced to pay war reparations by the Treaty of Versailles and was stripped of its colonies and significant territory along its borders. The German Revolution of 1918–19 put an end to the German Empire and established the Weimar Republic, an ultimately unstable parliamentary democracy.

In January 1933, Adolf Hitler, leader of the Nazi Party, used the economic hardships of the Great Depression along with popular resentment over the terms imposed on Germany at the end of World War I to establish a totalitarian regime. Germany quickly remilitarized, then annexed Austria and the German-speaking areas of Czechoslovakia in 1938. After seizing the rest of Czechoslovakia, Germany launched an invasion of Poland, which quickly grew into World War II. Following the Allied invasion of Normandy in June, 1944, the German Army was pushed back on all fronts until the final collapse in May 1945. Germany spent the entirety of the Cold War era divided into the NATO-aligned West Germany and Warsaw Pact-aligned East Germany.

In 1989, the Berlin Wall was opened, the Eastern Bloc collapsed, and East Germany was reunited with West Germany in 1990. Germany remains one of the economic powerhouses of Europe, contributing about one-quarter of the eurozone's annual gross domestic product.