History of Spain

The history of Spain dates to the Antiquity when the pre-Roman peoples of the Mediterranean coast of the Iberian Peninsula made contact with the Greeks and Phoenicians and the first writing systems known as Paleohispanic scripts were developed. During Classical Antiquity, the peninsula was the site of multiple successive colonizations of Greeks, Carthaginians, and Romans. Native peoples of the peninsula, such as the Tartessos people, intermingled with the colonizers to create a uniquely Iberian culture. The Romans referred to the entire Peninsula as Hispania, from where the modern name of Spain originates. The region was divided up, at various times, into different Roman provinces. As was the rest of the Western Roman Empire, Spain was subject to the numerous invasions of Germanic tribes during the 4th and 5th centuries CE, resulting in the loss of Roman rule and the establishment of Germanic kingdoms, most notably the Visigoths and the Suebi, marking the beginning of the Middle Ages in Spain.

Various Germanic kingdoms were established on the Iberian peninsula in the early 5th century CE in the wake of the fall of Roman control; germanic control lasted about 200 years until the Umayyad conquest of Hispania began in 711 and marked the introduction of Islam to the Iberian Peninsula. The region became known as Al-Andalus, and excepting for the small Kingdom of Asturias, a Christian rump state in the north of Iberia, the region remained under the control of Muslim-lead states for much of the Early Middle Ages, a period known as the Islamic Golden Age. By the time of the High Middle Ages, Christians from the north gradually expanded their control over Iberia, a period known as the Reconquista.

The early modern period is generally dated from the union of the Crowns of Castile and Aragon under the Catholic Monarchs, Isabella I of Castile and Ferdinand II of Aragon in 1469. It was under the rule of Philip II of Spain that the Spanish Golden Age flourished, the Spanish Empire reached its territorial and economic peak, and his palace at El Escorial became the center of artistic flourishing.

Spain's power would be further tested by their participation in the Eighty Years' War, whereby they tried and failed to recapture the newly independent Dutch Republic, and the Thirty Years' War, which resulted in continued decline of Habsburg power in favor of French Bourbon dynasty. The War of the Spanish Succession broke out between the French Bourbons and the Austrian Habsburgs over the right to succeed Charles II.

Concurrent with, and following, the Napoleonic period the Spanish American wars of independence resulted in the loss of most of Spain's territory in the Americas. During the re-establishment of the Bourbon rule in Spain, constitutional monarchy was introduced in 1813.

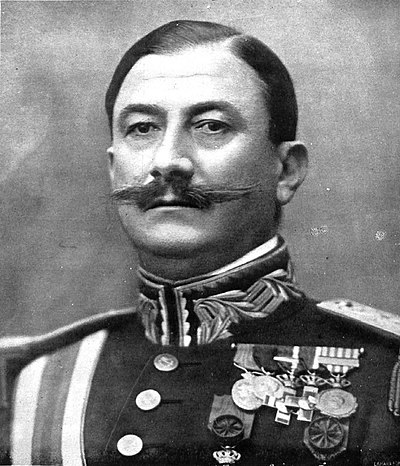

The twentieth century began for Spain in foreign and domestic turmoil; the Spanish-American War led to losses of Spanish colonial possessions and a series of military dictatorships, first under Miguel Primo de Rivera and secondly under Dámaso Berenguer. Ultimately, the political disorder within Spain led to the Spanish Civil War, in which the Republican forces squared off against the Nationalists. After much foreign intervention on both sides, the Nationalists emerged victorious, led by Francisco Franco, who would lead a fascist dictatorship for the almost four decades. Francisco's death ushered in a return of the monarchy King Juan Carlos I, which saw a liberalization of Spanish society and a re-engagement with the international community after the oppressive and isolated years under Franco. A new liberal Constitution was established in 1978. Spain entered the European Economic Community in 1986 (transformed into the European Union with the Maastricht Treaty of 1992), and the Eurozone in 1998. Juan Carlos abdicated in 2014, and was succeeded by his son Felipe VI, the current king.