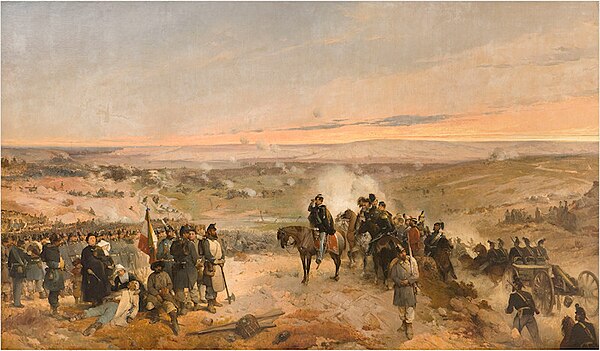

On 5 November 1854, the Russian 10th Division, under Lt. General F. I. Soymonov, launched a heavy attack on the allied right flank atop Home Hill. The assault was made by two columns of 35,000 men and 134 field artillery guns of the Russian 10th Division. When combined with other Russian forces in the area, the Russian attacking force would form a formidable army of some 42,000 men. The initial Russian assault was to be received by the British Second Division dug in on Home Hill with only 2,700 men and 12 guns. Both Russian columns moved in a flanking fashion east towards the British. They hoped to overwhelm this portion of the Allied army before reinforcements could arrive. The fog of the early morning hours aided the Russians by hiding their approach. Not all the Russian troops could fit on the narrow 300-meter-wide heights of Shell Hill. Accordingly, General Soymonov had followed Prince Alexander Menshikov's directive and deployed some of his force around the Careenage Ravine. Furthermore, on the night before the attack, Soymonov was ordered by General Peter A. Dannenberg to send part of his force north and east to the Inkerman Bridge to cover the crossing of Russian troop reinforcements under Lt. General P. Ya. Pavlov . Thus, Soymonov could not effectively employ all of his troops in the attack.

When dawn broke, Soymonov attacked the British positions on Home Hill with 6,300 men from the Kolyvansky, Ekaterinburg and Tomsky regiments. Soymonov also had a further 9,000 in reserve. The British had strong pickets and had ample warning of the Russian attack despite the early morning fog. The pickets, some of them at company strength, engaged the Russians as they moved to attack. The firing in the valley also gave warning to the rest of the Second Division, who rushed to their defensive positions.

The Russian infantry, advancing through the fog, were met by the advancing Second Division, who opened fire with their Pattern 1851 Enfield rifles, whereas the Russians were still armed with smoothbore muskets. The Russians were forced into a bottleneck owing to the shape of the valley, and came out on the Second Division's left flank. The Minié balls of the British rifles proved deadly accurate against the Russian attack. Those Russian troops that survived were pushed back at bayonet point. Eventually, the Russian infantry were pushed all the way back to their own artillery positions. The Russians launched a second attack, also on the Second Division's left flank, but this time in much larger numbers and led by Soymonov himself. Captain Hugh Rowlands, in charge of the British pickets, reported that the Russians charged "with the most fiendish yells you can imagine." At this point, after the second attack, the British position was incredibly weak. The British reinforcements arrived in the form of the Light Division which came up and immediately launched a counterattack along the left flank of the Russian front, forcing the Russians back. During this fighting Soymonov was killed by a British rifleman.

The rest of the Russian column proceeded down to the valley where they were attacked by British artillery and pickets, eventually being driven off. The resistance of the British troops here had blunted all of the initial Russian attacks. General Paulov, leading the Russian second column of some 15,000, attacked the British positions on Sandbag Battery. As they approached, the 300 British defenders vaulted the wall and charged with the bayonet, driving off the leading Russian battalions. Five Russian battalions were assailed in the flanks by the British 41st Regiment, who drove them back to the River Chernaya.

General Peter A Dannenberg took command of the Russian Army, and together with the uncommitted 9,000 men from the initial attacks, launched an assault on the British positions on Home Hill, held by the Second Division. The Guards Brigade of the First Division, and the Fourth Division were already marching to support the Second Division, but the British troops holding the Barrier withdrew, before it was re-taken by men from the 21st, 63rd Regiments and The Rifle Brigade. The Russians launched 7,000 men against the Sandbag Battery, which was defended by 2,000 British soldiers. So began a ferocious struggle which saw the battery change hands repeatedly.

At this point in the battle the Russians launched another assault on the Second Division's positions on Home Hill, but the timely arrival of the French Army under Pierre Bosquet and further reinforcements from the British Army repelled the Russian attacks. The Russians had now committed all of their troops and had no fresh reserves with which to act. Two British 18-pounder guns along with field artillery bombarded the 100-gun strong Russian positions on Shell Hill in counter-battery fire. With their batteries on Shell Hill taking withering fire from the British guns, their attacks rebuffed at all points, and lacking fresh infantry, the Russians began to withdraw. The allies made no attempt to pursue them. Following the battle, the allied regiments stood down and returned to their siege positions.