History of Egypt

The history of Egypt is marked by its rich and enduring legacy, which owes much to the fertile lands nourished by the Nile River and the achievements of its native inhabitants, as well as external influences. The mysteries of Egypt's ancient past began to unravel with the decipherment of Egyptian hieroglyphs, a milestone aided by the discovery of the Rosetta Stone.

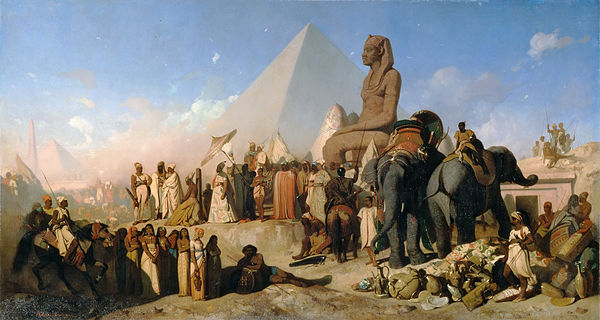

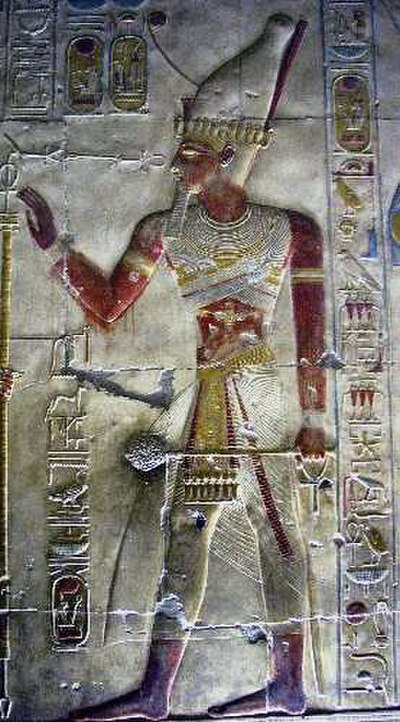

Around 3150 BCE, the political consolidation of Upper and Lower Egypt brought forth the inception of ancient Egyptian civilization, under the rule of King Narmer during the First Dynasty. This period of predominantly native Egyptian rule persisted until the conquest by the Achaemenid Empire in the sixth century BCE.

In 332 BCE, Alexander the Great entered Egypt during his campaign to overthrow the Achaemenid Empire, establishing the short-lived Macedonian Empire. This era heralded the rise of the Hellenistic Ptolemaic Kingdom, founded in 305 BCE by Ptolemy I Soter, one of Alexander's former generals. The Ptolemies grappled with native uprisings and were embroiled in foreign and civil conflicts, leading to the kingdom's gradual decline and eventual incorporation into the Roman Empire, following the demise of Cleopatra.

Roman dominion over Egypt, which included the Byzantine period, spanned from 30 BCE to 641 CE, with a brief interlude of Sasanian Empire control from 619 to 629, known as Sasanian Egypt. After the Muslim conquest of Egypt, the region became part of various Caliphates and Muslim dynasties, including the Rashidun Caliphate (632-661), Umayyad Caliphate (661–750), Abbasid Caliphate (750–935), Fatimid Caliphate (909–1171), Ayyubid Sultanate (1171–1260), and the Mamluk Sultanate (1250–1517). In 1517, the Ottoman Empire, under Selim I, captured Cairo, integrating Egypt into their realm.

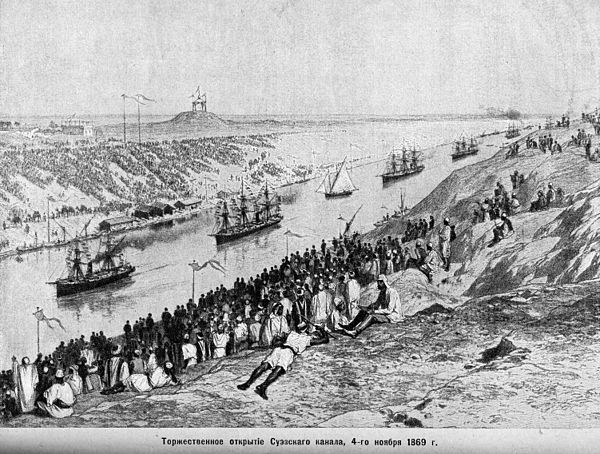

Egypt remained under Ottoman rule until 1805, except for a period of French occupation from 1798 to 1801. Starting in 1867, Egypt attained nominal autonomy as the Khedivate of Egypt, but British control was established in 1882 following the Anglo-Egyptian War. After World War I and the Egyptian revolution of 1919, the Kingdom of Egypt emerged, albeit with the United Kingdom retaining authority over foreign affairs, defense, and other key matters. This British occupation persisted until 1954, when the Anglo-Egyptian agreement led to a complete withdrawal of British forces from the Suez Canal.

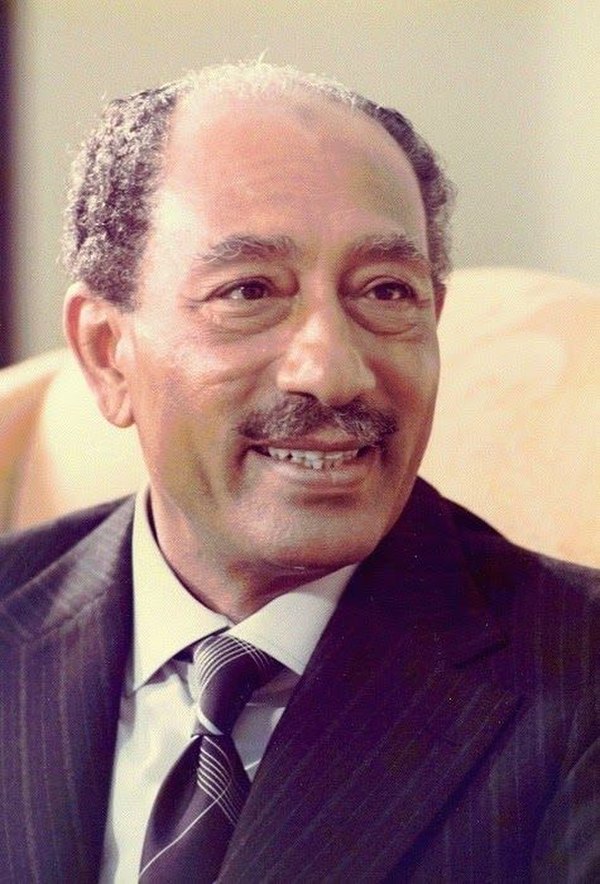

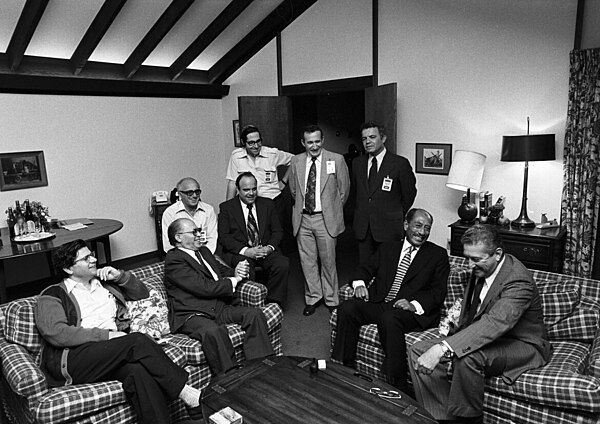

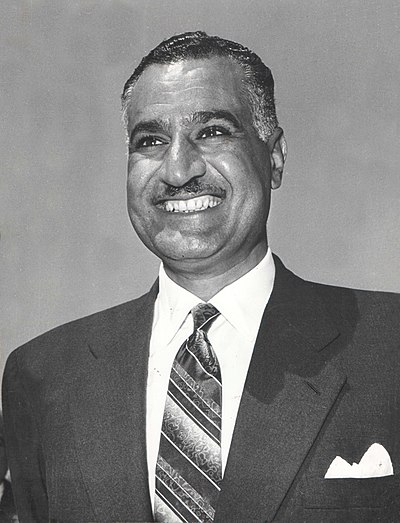

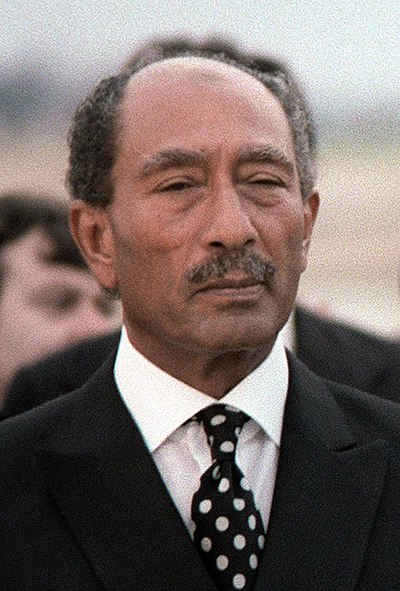

In 1953, the modern Republic of Egypt was founded, and in 1956, with the full evacuation of British forces from the Suez Canal, President Gamal Abdel Nasser introduced numerous reforms and briefly formed the United Arab Republic with Syria. Nasser's leadership encompassed the Six-Day War and the formation of the Non-Aligned Movement. His successor, Anwar Sadat, who held office from 1970 to 1981, departed from Nasser's political and economic principles, reintroduced a multi-party system, and initiated the Infitah economic policy. Sadat led Egypt in the Yom Kippur War of 1973, reclaiming Egypt's Sinai Peninsula from Israeli occupation, eventually culminating in the Egypt-Israel peace treaty.

Recent Egyptian history has been defined by events following nearly three decades of Hosni Mubarak's presidency. The Egyptian revolution of 2011 led to Mubarak's removal from power and the election of Mohamed Morsi as Egypt's first democratically elected president. Subsequent unrest and disputes following the 2011 revolution resulted in the 2013 Egyptian coup d'état, Morsi's imprisonment, and the election of Abdel Fattah al-Sisi as president in 2014.