Republic of Venice

The Republic of Venice was a sovereign state and maritime republic in parts of present-day Italy which existed for 1100 years from 697 until 1797 CE. Centered on the lagoon communities of the prosperous city of Venice, it incorporated numerous overseas possessions in modern Croatia, Slovenia, Montenegro, Greece, Albania and Cyprus. The republic grew into a trading power during the Middle Ages and strengthened this position in the Renaissance. Citizens spoke the still-surviving Venetian language, although publishing in (Florentine) Italian became the norm during the Renaissance.

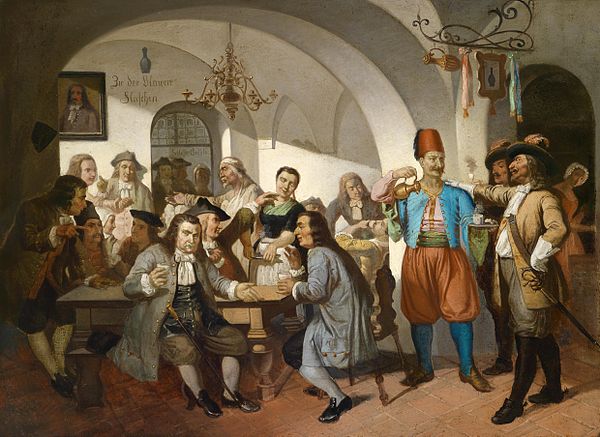

In its early years, it prospered on the salt trade. In subsequent centuries, the city state established a thalassocracy. It dominated trade on the Mediterranean Sea, including commerce between Europe and North Africa, as well as Asia. The Venetian navy was used in the Crusades, most notably in the Fourth Crusade. However, Venice perceived Rome as an enemy and maintained high levels of religious and ideological independence personified by the patriarch of Venice and a highly developed independent publishing industry that served as a haven from Catholic censorship for many centuries. Venice achieved territorial conquests along the Adriatic Sea. It became home to an extremely wealthy merchant class, who patronised renowned art and architecture along the city's lagoons. Venetian merchants were influential financiers in Europe. The city was also the birthplace of great European explorers, such as Marco Polo, as well as Baroque composers such as Antonio Vivaldi and Benedetto Marcello and famous painters such as the Renaissance master, Titian.

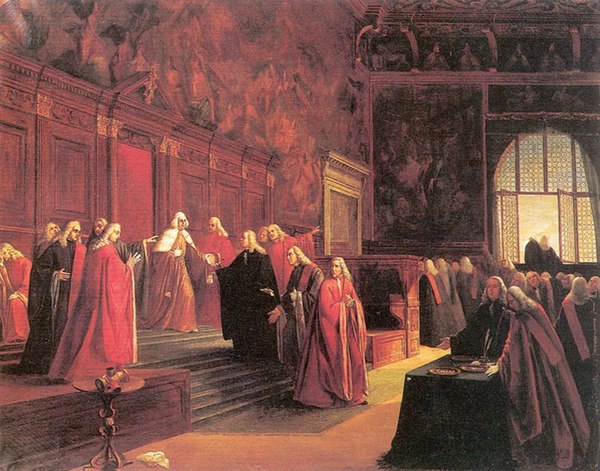

The republic was ruled by the doge, who was elected by members of the Great Council of Venice, the city-state's parliament, and ruled for life. The ruling class was an oligarchy of merchants and aristocrats. Venice and other Italian maritime republics played a key role in fostering capitalism. Venetian citizens generally supported the system of governance. The city-state enforced strict laws and employed ruthless tactics in its prisons.

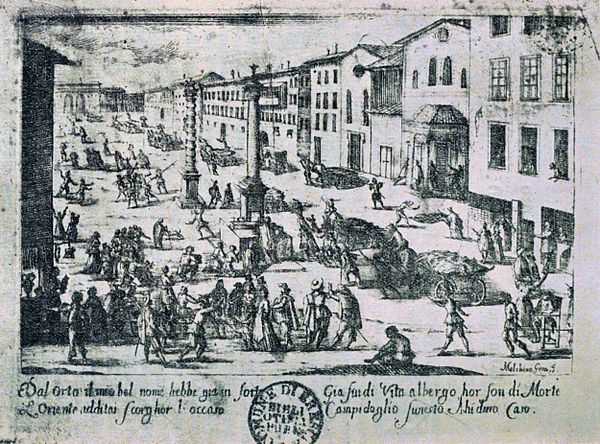

The opening of new trade routes to the Americas and the East Indies via the Atlantic Ocean marked the beginning of Venice's decline as a powerful maritime republic. The city state suffered defeats from the navy of the Ottoman Empire. In 1797, the republic was plundered by retreating Austrian and then French forces, following an invasion by Napoleon Bonaparte, and the Republic of Venice was split into the Austrian Venetian Province, the Cisalpine Republic, a French client state, and the Ionian French departments of Greece. Venice became part of a unified Italy in the 19th century.