History of Hungary

Hungary borders roughly corresponds to the Great Hungarian Plain (the Pannonian Basin) in Central Europe. During the Iron Age, it was located at the crossroads between the cultural spheres of the Celtic tribes (such as the Scordisci, Boii and Veneti), Dalmatian tribes (such as the Dalmatae, Histri and Liburni) and the Germanic tribes (such as the Lugii, Gepids and Marcomanni).

The name "Pannonian" comes from Pannonia, a province of the Roman Empire. Only the western part of the territory (the so-called Transdanubia) of modern Hungary formed part of Pannonia. The Roman control collapsed with the Hunnic invasions of 370–410, and Pannonia was part of the Ostrogothic Kingdom during the late 5th to mid 6th century, succeeded by the Avar Khaganate (6th to 9th centuries). The Hungarians took possession of the Carpathian Basin in a pre-planned manner, with a long move-in between 862–895.

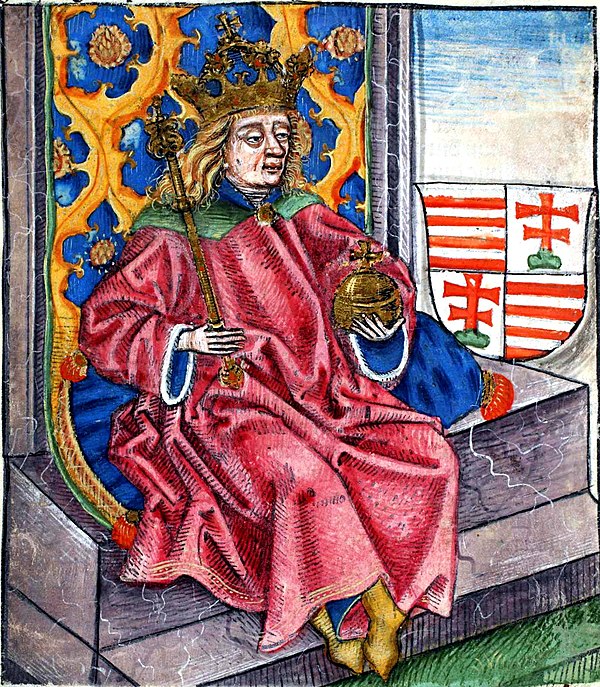

The Christian Kingdom of Hungary was established in 1000 under King Saint Stephen, ruled by the Árpád dynasty for the following three centuries. In the high medieval period, the kingdom expanded to the Adriatic coast and entered a personal union with Croatia during the reign of King Coloman in 1102. In 1241 during the reign of King Béla IV, Hungary was invaded by the Mongols under Batu Khan. The outnumbered Hungarians were decisively defeated at the Battle of Mohi by the Mongol army. In this invasion more than 500,000 Hungarian people were massacred and the whole kingdom reduced to ashes. The paternal lineage of the ruling Árpád dynasty came to end in 1301, and all of the subsequent kings of Hungary (with the exception of King Matthias Corvinus) were cognatic descendants of the Árpád dynasty. Hungary bore the brunt of the Ottoman wars in Europe during the 15th century. The peak of this struggle took place during the reign of Matthias Corvinus (r. 1458–1490). The Ottoman–Hungarian wars concluded in significant loss of territory and the partition of the kingdom after the Battle of Mohács of 1526.

Defense against Ottoman expansion shifted to Habsburg Austria, and the remainder of the Hungarian kingdom came under the rule of the Habsburg emperors. The lost territory was recovered with the conclusion of the Great Turkish War, thus the whole of Hungary became part of the Habsburg monarchy. Following the nationalist uprisings of 1848, the Austro-Hungarian Compromise of 1867 elevated Hungary's status by the creation of a joint monarchy. The territory grouped under the Habsburg Archiregnum Hungaricum was much larger than modern Hungary, following the Croatian–Hungarian Settlement of 1868 which settled the political status of the Kingdom of Croatia-Slavonia within the Lands of the Crown of Saint Stephen.

After the first World War, the Central Powers enforced the dissolution of the Habsburg monarchy. The treaties of Saint-Germain-en-Laye and Trianon detached around 72% of the territory of the Kingdom of Hungary, which was ceded to Czechoslovakia, the Kingdom of Romania, the Kingdom of Serbs, Croats and Slovenes, the First Austrian Republic, the Second Polish Republic and the Kingdom of Italy. Afterwards a short-lived People's Republic was declared. It was followed by a restored Kingdom of Hungary but was governed by a regent, Miklós Horthy. He officially represented the Hungarian monarchy of Charles IV, Apostolic King of Hungary, who was held in captivity during his last months at Tihany Abbey. Between 1938 and 1941, Hungary recovered part of her lost territories. During World War II Hungary came under German occupation in 1944, then under Soviet occupation until the end of the war. After World War II, the Second Hungarian Republic was established within Hungary's current-day borders as a socialist People's Republic, lasting from 1949 to the end of communism in Hungary in 1989. The Third Republic of Hungary was established under an amended version of the constitution of 1949, with a new constitution adopted in 2011. Hungary joined the European Union in 2004.