Knights Hospitaller

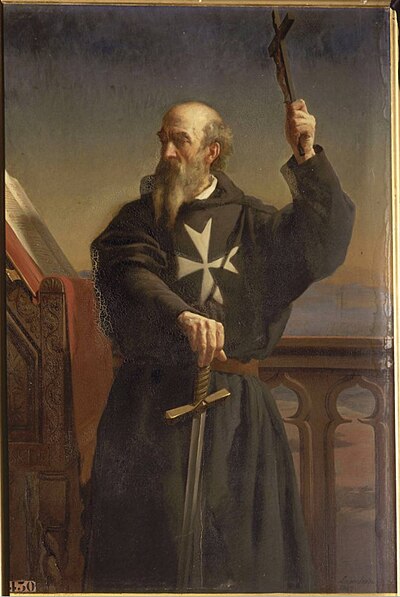

The Order of Knights of the Hospital of Saint John of Jerusalem, commonly known as the Knights Hospitaller, was a medieval and early modern Catholic military order. It was headquartered in the Kingdom of Jerusalem until 1291, on the island of Rhodes from 1310 until 1522, in Malta from 1530 until 1798 and at Saint Petersburg from 1799 until 1801.

The Hospitallers arose in the early 12th century, during the time of the Cluniac movement (a Benedictine Reform movement). Early in the 11th century, merchants from Amalfi founded a hospital in the Muristan district of Jerusalem, dedicated to John the Baptist, to provide care for sick, poor, or injured pilgrims to the Holy Land. Blessed Gerard became its head in 1080. After the conquest of Jerusalem in 1099 during the First Crusade, a group of Crusaders formed a religious order to support the hospital. Some scholars consider that the Amalfitan order and hospital were different from Gerard's order and its hospital.

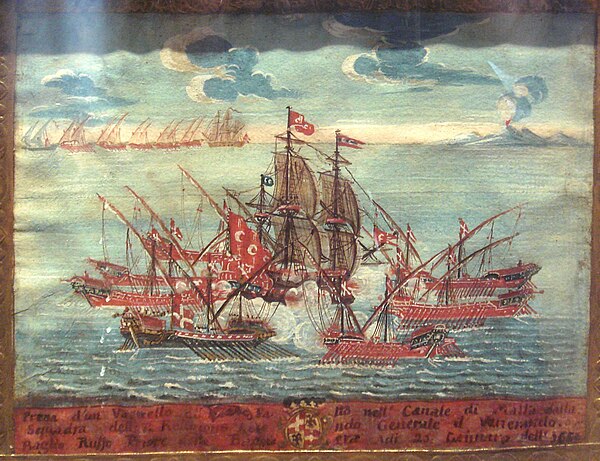

The organization became a military religious order under its own papal charter, charged with the care and defense of the Holy Land. Following the conquest of the Holy Land by Islamic forces, the knights operated from Rhodes, over which they were sovereign, and later from Malta, where they administered a vassal state under the Spanish viceroy of Sicily. The Hospitallers were one of the smallest groups to briefly colonize parts of the Americas: they acquired four Caribbean islands in the mid-17th century, which they turned over to France in the 1660s.

The knights became divided during the Protestant Reformation, when rich commanderies of the order in northern Germany and the Netherlands became Protestant and largely separated from the Roman Catholic main stem, remaining separate to this day, although ecumenical relations between the descendant chivalric orders are amicable. The order was suppressed in England, Denmark, and some other parts of northern Europe, and it was further damaged by Napoleon's capture of Malta in 1798, following which it became dispersed throughout Europe.