The siege and massacre of Tripolitsa in 1821 was a pivotal event during the Greek War of Independence. Tripolitsa, located in the heart of the Peloponnese, was the capital of the Ottoman Morea Eyalet and a symbol of Ottoman authority. Its population included wealthy Turks, Jews, and Ottoman refugees. Historical massacres of its Greek inhabitants in 1715, 1770, and early 1821 intensified Greek resentment.

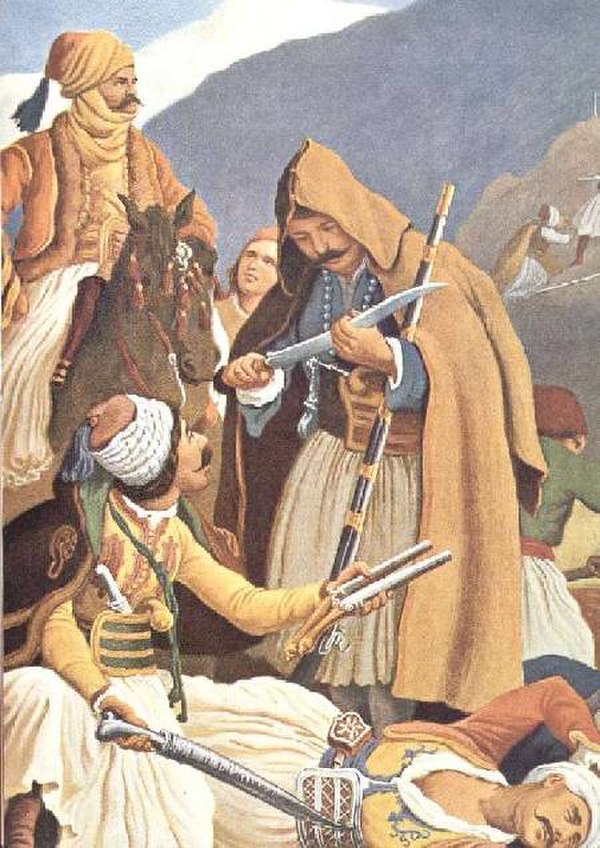

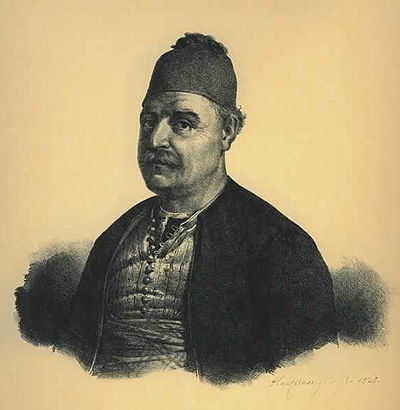

Theodoros Kolokotronis, a key Greek revolutionary leader, targeted Tripolitsa, establishing camps and headquarters around it. His forces were joined by Maniot troops under Petros Mavromichalis and various other commanders. The Ottoman garrison, led by Kehayabey Mustafa and reinforced by troops from Hursid Pasha, faced a challenging siege.

Despite initial Ottoman resistance, conditions inside Tripolitsa worsened due to food and water shortages. Kolokotronis negotiated with the Albanian defenders for their safe passage, weakening the Ottoman defense. By September 1821, the Greeks had consolidated around Tripolitsa, and on September 23, they breached the city walls, leading to a rapid takeover.

The capture of Tripolitsa was followed by a brutal massacre of its Muslim (mainly Turks) and Jewish inhabitants. Eyewitness accounts, including those of Thomas Gordon and William St. Clair, describe horrific atrocities committed by the Greek forces, with estimates of up to 32,000 people killed, including women and children. The massacre was part of a series of retaliatory acts against Muslims in the Peloponnese.

The Greek forces' actions during the siege and massacre, marked by religious fervor and revenge, mirrored earlier Ottoman atrocities, such as the Massacre of Chios. While the Jewish community suffered greatly, historians like Steven Bowman suggest their targeting was incidental to the larger aim of eliminating the Turks.

The capture of Tripolitsa significantly boosted Greek morale, demonstrating the feasibility of victory against the Ottomans. It also led to a split among the Greek revolutionaries, with some leaders decrying the atrocities. This division foreshadowed future internal conflicts within the Greek independence movement.