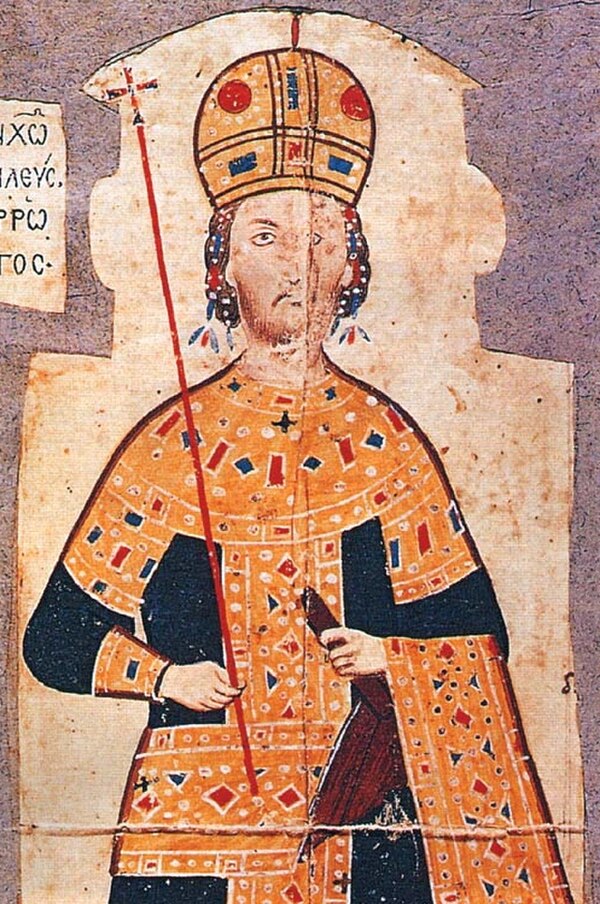

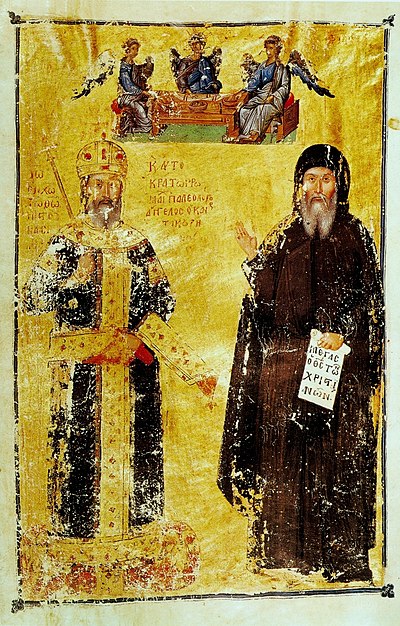

Byzantine Empire: Palaiologos dynasty

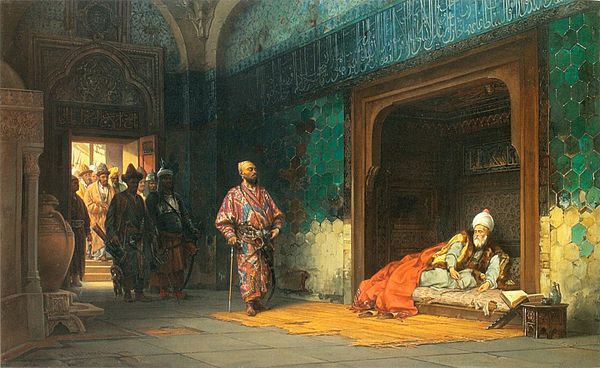

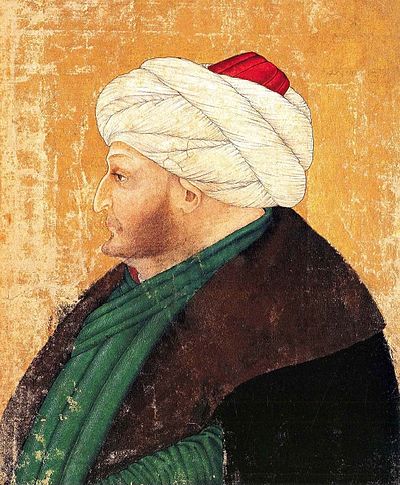

The Byzantine Empire was ruled by the Palaiologos dynasty in the period between 1261 and 1453, from the restoration of Byzantine rule to Constantinople by the usurper Michael VIII Palaiologos following its recapture from the Latin Empire, founded after the Fourth Crusade (1204), up to the Fall of Constantinople to the Ottoman Empire. Together with the preceding Nicaean Empire and the contemporary Frankokratia, this period is known as the late Byzantine Empire.

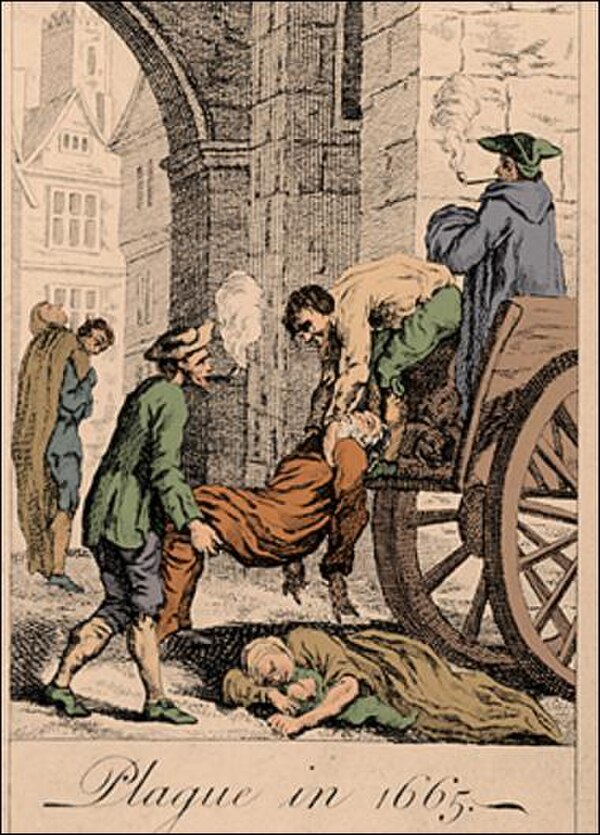

The loss of land in the East to the Turks and in the West to the Bulgarians coincided with two disastrous civil wars, the Black Death and the 1354 earthquake at Gallipoli which allowed the Turks to occupy the peninsula. By 1380, the Byzantine Empire consisted of the capital Constantinople and a few other isolated exclaves, which only nominally recognized the Emperor as their lord. Nonetheless, Byzantine diplomacy, political intigue and the invasion of Anatolia by Timur allowed Byzantium to survive until 1453. The last remnants of the Byzantine Empire, the Despotate of the Morea and the Empire of Trebizond, fell shortly afterwards.

However, the Palaiologan period witnessed a renewed flourishing in art and the letters, in what has been called the Palaiologian Renaissance. The migration of Byzantine scholars to the West also helped to spark the Italian Renaissance.