History of Albania

Classical antiquity in Albania was marked by the presence of several Illyrian tribes such as the Albanoi, Ardiaei, and Taulantii, alongside Greek colonies like Epidamnos-Dyrrhachium and Apollonia. The earliest notable Illyrian polity was centered around the Enchele tribe. Around 400 BCE, King Bardylis, the first known Illyrian king, sought to establish Illyria as a significant regional power, successfully uniting southern Illyrian tribes and expanding territory by defeating Macedonians and Molossians. His efforts established Illyria as a dominant regional force prior to the rise of Macedon.

In the late 4th century BCE, the kingdom of the Taulantii, under King Glaukias, influenced the southern Illyrian affairs significantly, extending their sway into the Epirote state through alliances with Pyrrhus of Epirus. By the 3rd century BCE, the Ardiaei had formed the largest Illyrian kingdom, which controlled a vast region from the Neretva River to the borders of Epirus. This kingdom was a formidable maritime and land power until the Illyrian defeat in the Illyro-Roman Wars (229–168 BCE). The region eventually fell under Roman rule by the early 2nd century BCE, and it became part of the Roman provinces of Dalmatia, Macedonia, and Moesia Superior.

Throughout the Middle Ages, the area saw the formation of the Principality of Arbër and integration into various empires, including the Venetian and Serbian Empires. By the mid-14th to the late 15th centuries, Albanian principalities emerged but fell to the Ottoman Empire, under which Albania remained largely until the early 20th century. The national awakening in the late 19th century eventually led to the Albanian Declaration of Independence in 1912.

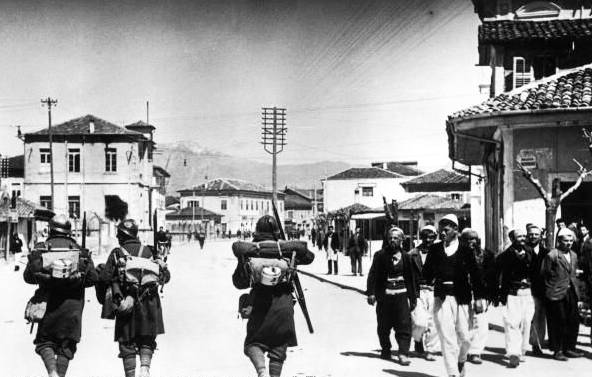

Albania experienced brief periods of monarchy in the early 20th century, followed by Italian occupation before World War II and subsequent German occupation. Post-war, Albania was governed by a communist regime under Enver Hoxha until 1985. The regime collapsed in 1990 amid economic crisis and social unrest, leading to significant Albanian emigration. The political and economic stabilization in the early 21st century allowed Albania to join NATO in 2009, and it is currently a candidate for European Union membership.