History of Portugal

The Roman invasion in the 3rd century BCE lasted several centuries, and developed the Roman provinces of Lusitania in the south and Gallaecia in the north. Following the fall of Rome, Germanic tribes controlled the territory between the 5th and 8th centuries, including the Kingdom of the Suebi centred in Braga and the Visigothic Kingdom in the south.

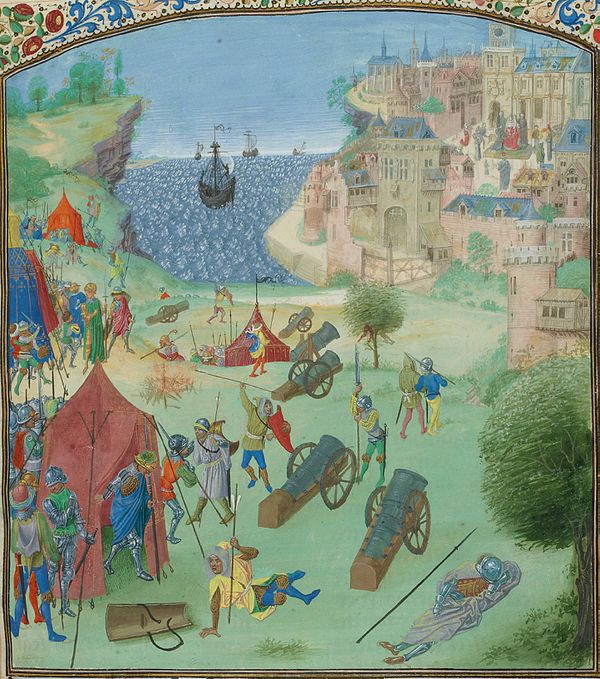

The 711–716 invasion by the Islamic Umayyad Caliphate conquered the Visigoth Kingdom and founded the Islamic State of Al-Andalus, gradually advancing through Iberia. In 1095, Portugal broke away from the Kingdom of Galicia. Henry's son Afonso Henriques proclaimed himself king of Portugal in 1139. The Algarve was conquered from the Moors in 1249, and in 1255 Lisbon became the capital. Portugal's land boundaries have remained almost unchanged since then. During the reign of King John I, the Portuguese defeated the Castilians in a war over the throne (1385) and established a political alliance with England (by the Treaty of Windsor in 1386).

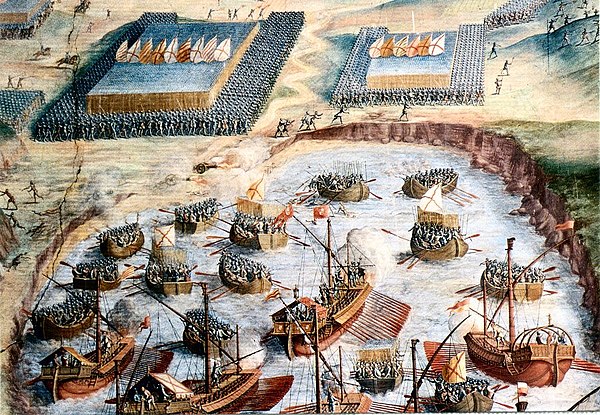

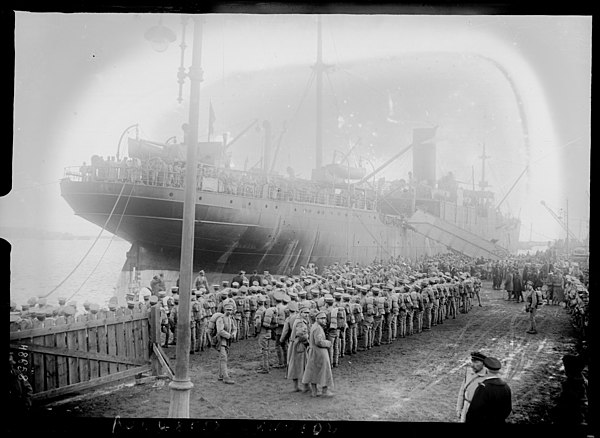

From the late Middle Ages, in the 15th and 16th centuries, Portugal ascended to the status of a world power during Europe's "Age of Discovery" as it built up a vast empire. Signs of military decline began with the Battle of Alcácer Quibir in Morocco in 1578 and Spain's attempt to conquer England in 1588 by means of the Spanish Armada – Portugal was then in a dynastic union with Spain and had contributed ships to the Spanish fleet. Further setbacks included the destruction of much of its capital city in an earthquake in 1755, occupation during the Napoleonic Wars and the loss of its largest colony, Brazil, in 1822. From the middle of the 19th century to the late 1950s, nearly two million Portuguese left Portugal to live in Brazil and the United States.

In 1910, a revolution deposed the monarchy. A military coup in 1926 installed a dictatorship that remained until another coup in 1974. The new government instituted sweeping democratic reforms and granted independence to all of Portugal's African colonies in 1975. Portugal is a founding member of the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO), the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD), and the European Free Trade Association (EFTA). It entered the European Economic Community (now the European Union) in 1986.