History of Armenia

Armenia is located in the highlands surrounding the Biblical mountains of Ararat. The original Armenian name for the country was Hayk, later Hayastan. The historical enemy of Hayk (the legendary ruler of Armenia) was Bel, or in other words Baal. The name Armenia was given to the country by the surrounding states, and it is traditionally derived from Armenak or Aram (the great-grandson of Haik's great-grandson, and another leader who is, according to Armenian tradition, the ancestor of all Armenians). In the Bronze Age, several states flourished in the area of Greater Armenia, including the Hittite Empire (at the height of its power), Mitanni (southwestern historical Armenia), and Hayasa-Azzi (1600–1200 BCE). Soon after the Hayasa-Azzi were the Nairi tribal confederation (1400–1000 BCE) and the Kingdom of Urartu (1000–600 BCE), who successively established their sovereignty over the Armenian Highland. Each of the aforementioned nations and tribes participated in the ethnogenesis of the Armenian people. Yerevan, the modern capital of Armenia, dates back to the 8th century BCE, with the founding of the fortress of Erebuni in 782 BCE by King Argishti I at the western extreme of the Ararat plain. Erebuni has been described as "designed as a great administrative and religious centre, a fully royal capital."

The Iron Age kingdom of Urartu (Assyrian for Ararat) was replaced by the Orontid dynasty. Following Persian and subsequent Macedonian rule, the Artaxiad dynasty from 190 BCE gave rise to the Kingdom of Armenia which rose to the peak of its influence under Tigranes the Great before falling under Roman rule.

In 301, Arsacid Armenia was the first sovereign nation to accept Christianity as a state religion. The Armenians later fell under Byzantine, Sassanid Persian, and Islamic hegemony, but reinstated their independence with the Bagratid Dynasty kingdom of Armenia. After the fall of the kingdom in 1045, and the subsequent Seljuk conquest of Armenia in 1064, the Armenians established a kingdom in Cilicia, where they prolonged their sovereignty to 1375.

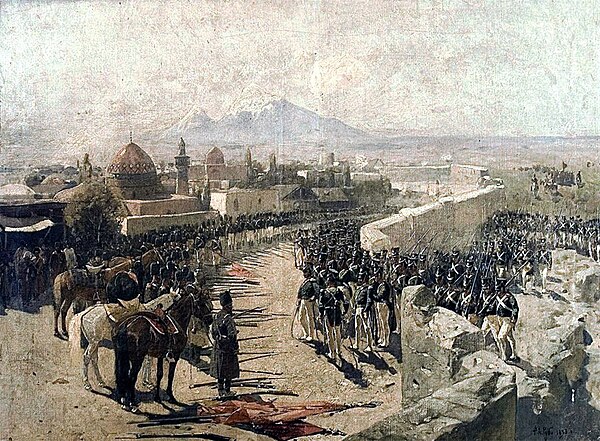

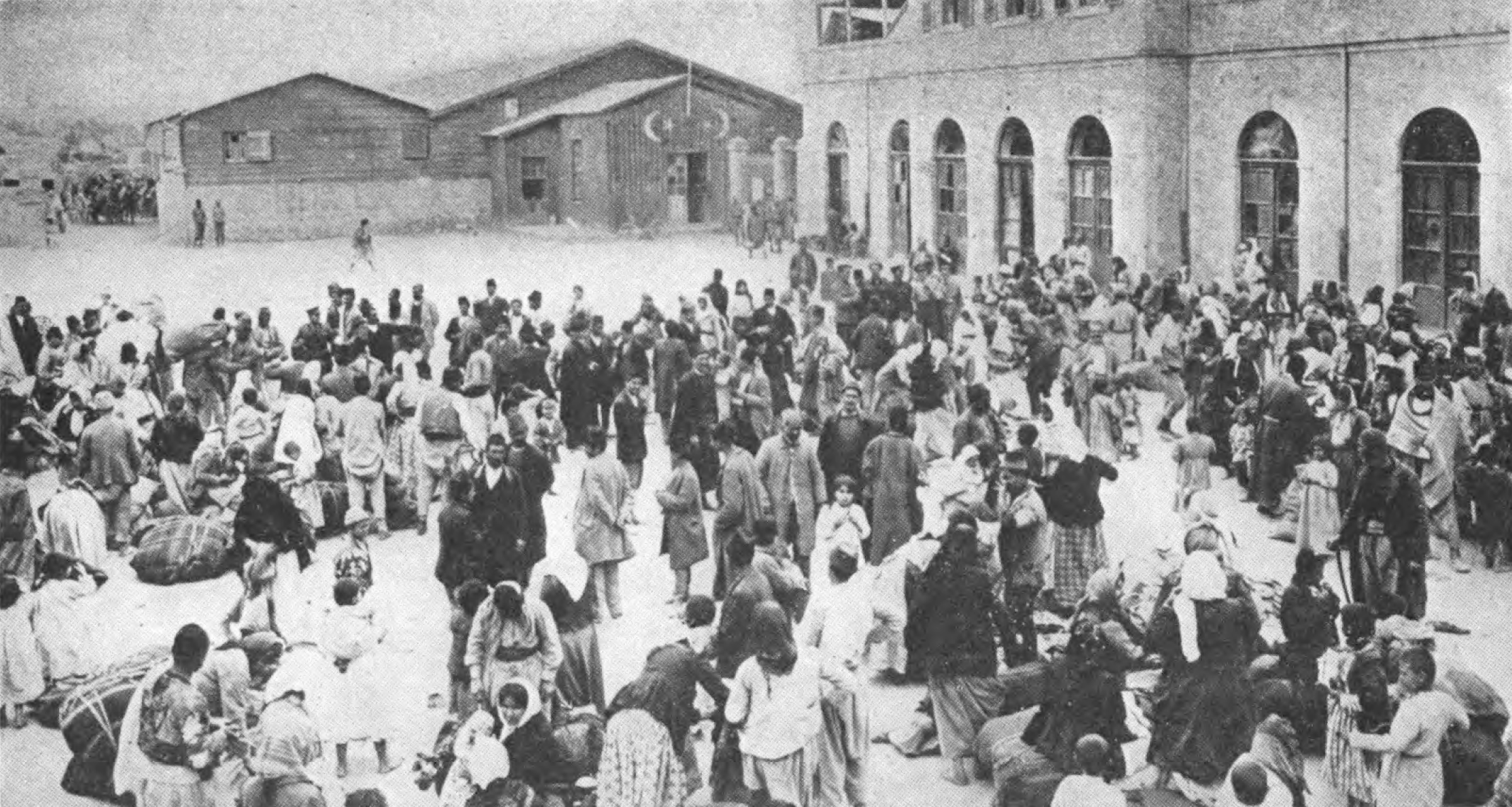

Starting in the early 16th century, Greater Armenia came under Safavid Persian rule; however, over the centuries Western Armenia fell under Ottoman rule, while Eastern Armenia remained under Persian rule. By the 19th century, Eastern Armenia was conquered by Russia and Greater Armenia was divided between the Ottoman and Russian Empires.