Turkish War of Independence

The Turkish War of Independence was a series of military campaigns waged by the Turkish National Movement after parts of the Ottoman Empire were occupied and partitioned following its defeat in World War I. These campaigns were directed against Greece in the west, Armenia in the east, France in the south, loyalists and separatists in various cities, and British and Ottoman troops around Constantinople (İstanbul).

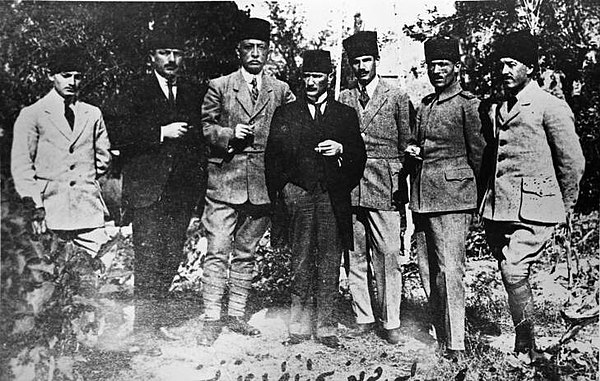

While World War I ended for the Ottoman Empire with the Armistice of Mudros, the Allied Powers continued occupying and seizing land for imperialist designs, as well as to prosecute former members of the Committee of Union and Progress and those involved in the Armenian genocide. Ottoman military commanders therefore refused orders from both the Allies and the Ottoman government to surrender and disband their forces. This crisis reached a head when sultan Mehmed VI dispatched Mustafa Kemal Pasha (Atatürk), a well-respected and high-ranking general, to Anatolia to restore order; however, Mustafa Kemal became an enabler and eventually leader of Turkish nationalist resistance against the Ottoman government, Allied powers, and Christian minorities.

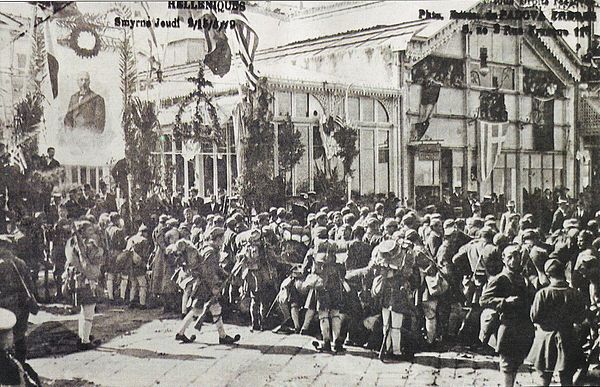

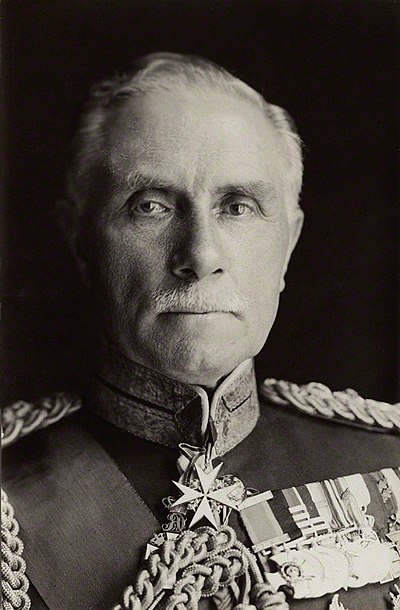

In the ensuing war, irregular militia defeated the French forces in the south, and undemobilized units went on to partition Armenia with Bolshevik forces, resulting in the Treaty of Kars (October 1921). The Western Front of the independence war was known as the Greco-Turkish War, in which Greek forces at first encountered unorganized resistance. However İsmet Pasha's organization of militia into a regular army paid off when Ankara forces fought the Greeks in the Battles of First and Second İnönü. The Greek army emerged victorious in the Battle of Kütahya-Eskişehir and decided to drive on the nationalist capital of Ankara, stretching their supply lines. The Turks checked their advance in the Battle of Sakarya and counter-attacked in the Great Offensive, which expelled Greek forces from Anatolia in the span of three weeks. The war effectively ended with the recapture of İzmir and the Chanak Crisis, prompting the signing of another armistice in Mudanya.

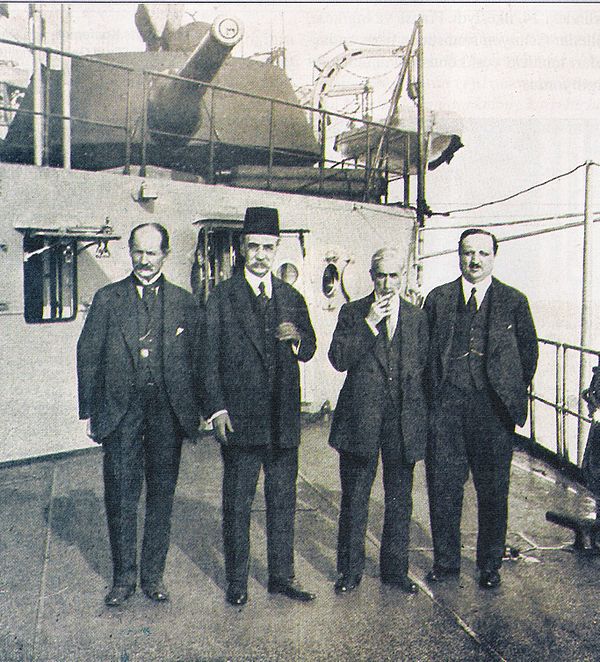

The Grand National Assembly in Ankara was recognized as the legitimate Turkish government, which signed the Treaty of Lausanne (July 1923), a treaty more favorable to Turkey than the Sèvres Treaty. The Allies evacuated Anatolia and Eastern Thrace, the Ottoman government was overthrown and the monarchy abolished, and the Grand National Assembly of Turkey (which remains Turkey's primary legislative body today) declared the Republic of Turkey on 29 October 1923. With the war, a population exchange between Greece and Turkey, the partitioning of the Ottoman Empire, and the abolition of the sultanate, the Ottoman era came to an end, and with Atatürk's reforms, the Turks created the modern, secular nation-state of Turkey. On 3 March 1924, the Ottoman caliphate was also abolished.