World War I

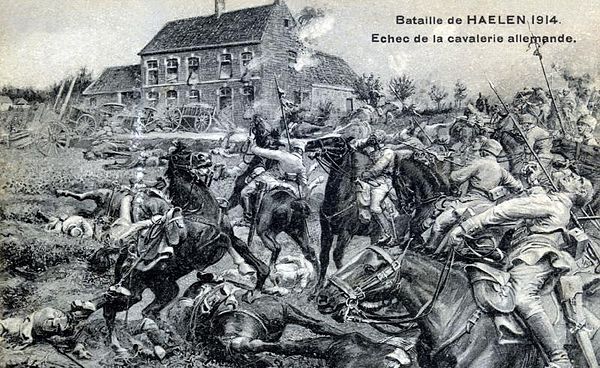

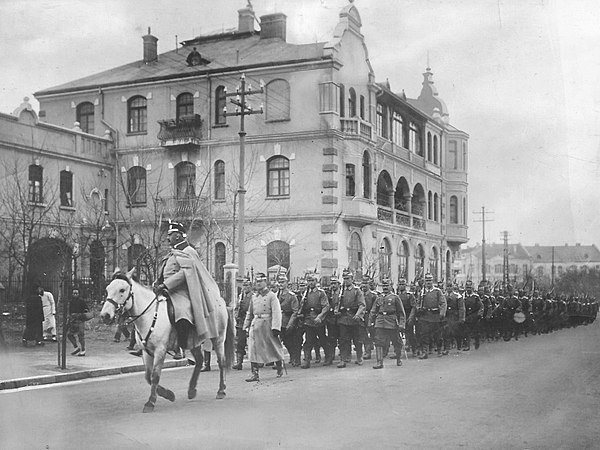

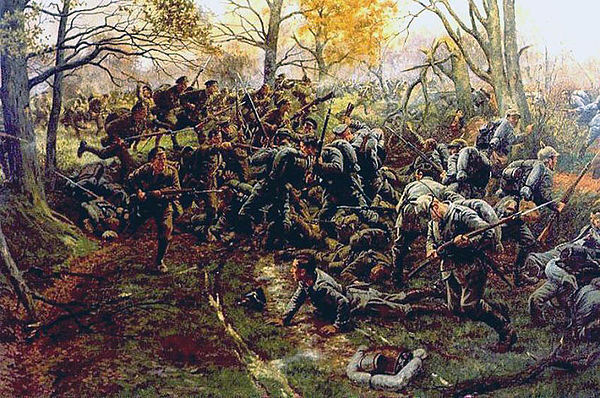

World War I or the First World War, often abbreviated as WWI or WW1, began on 28 July 1914 and ended on 11 November 1918. Referred to by contemporaries as the "Great War", its belligerents included much of Europe, the Russian Empire, the United States, and the Ottoman Empire, with fighting also expanding into the Middle East, Africa, and parts of Asia. One of the deadliest conflicts in history, an estimated 9 million people were killed in combat, while over 5 million civilians died from military occupation, bombardment, hunger, and disease. Millions of additional deaths resulted from genocides within the Ottoman Empire and the 1918 influenza pandemic, which was exacerbated by the movement of combatants during the war.

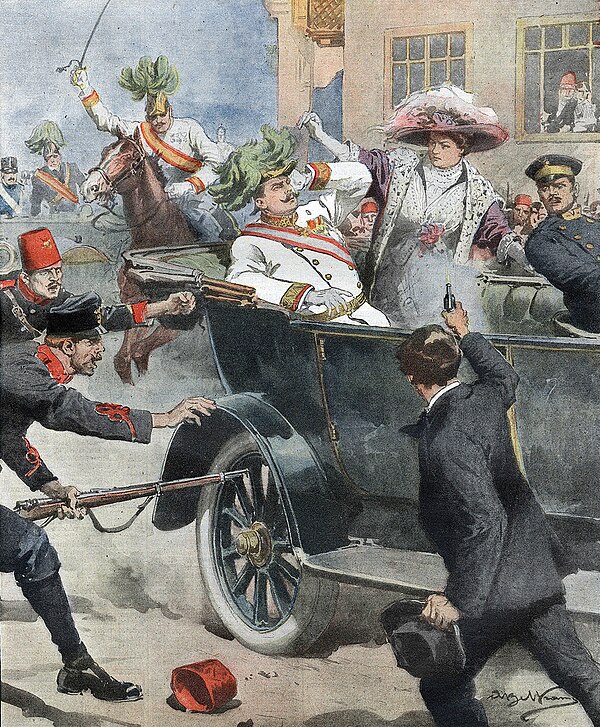

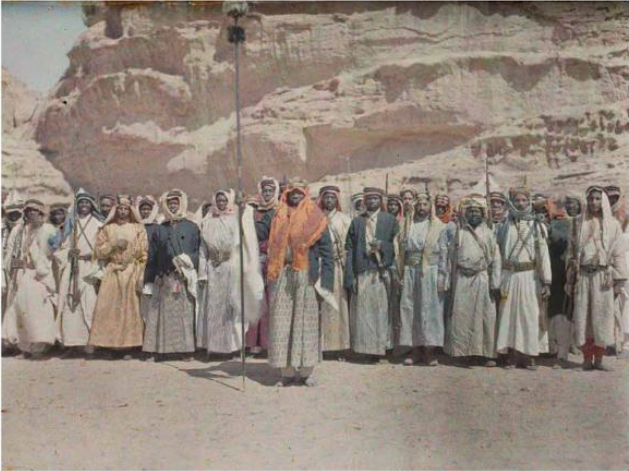

By 1914, the European great powers were divided into the Triple Entente of France, Russia, and Britain; and the Triple Alliance of Germany, Austria-Hungary, and Italy. Tensions in the Balkans came to a head on 28 June 1914 following the assassination of Archduke Franz Ferdinand, the Austro-Hungarian heir, by Gavrilo Princip, a Bosnian Serb. Austria-Hungary blamed Serbia, which led to the July Crisis, an unsuccessful attempt to avoid conflict through diplomacy. Russia came to Serbia's defense following Austria-Hungary's declaration of war on the latter on 28 July, and by 4 August, the system of alliances drew in Germany, France, and Britain, along with their respective colonies. In November, the Ottoman Empire, Germany, and Austria-Hungary formed the Central Powers, while in April 1915, Italy switched sides to join Britain, France, Russia, and Serbia in forming the Allies of World War I.

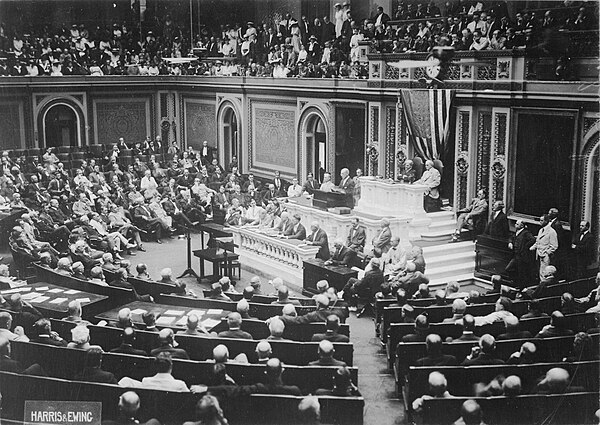

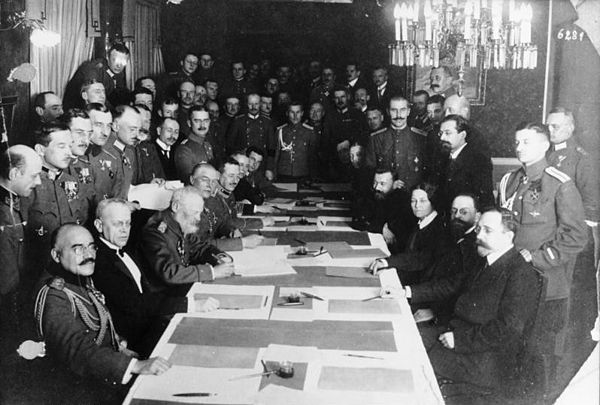

Towards the end of 1918, the Central Powers began to collapse; Bulgaria signed an armistice on 29 September, followed by the Ottomans on 31 October, then Austria-Hungary on 3 November. Isolated, facing the German Revolution at home and a military on the verge of mutiny, Kaiser Wilhelm abdicated on 9 November, and the new German government signed the Armistice of 11 November 1918, bringing the conflict to a close. The Paris Peace Conference of 1919–1920 imposed various settlements on the defeated powers, with the best-known of these being the Treaty of Versailles. The dissolution of the Russian, German, Ottoman, and Austro-Hungarian empires led to numerous uprisings and the creation of independent states, including Poland, Czechoslovakia, and Yugoslavia. For reasons that are still debated, failure to manage the instability that resulted from this upheaval during the interwar period ended with the outbreak of World War II in September 1939.