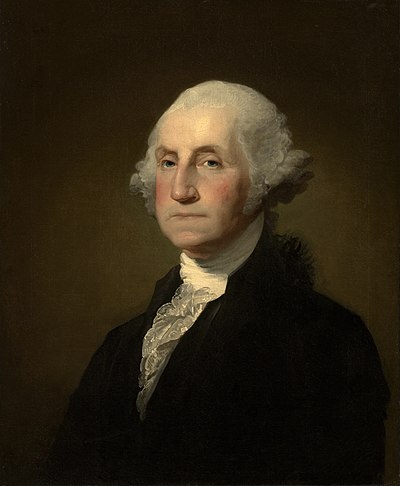

George Washington

George Washington (February 22, 1732 – December 14, 1799) was an American military officer, statesman, and Founding Father who served as the first president of the United States from 1789 to 1797. Appointed by the Continental Congress as commander of the Continental Army, Washington led Patriot forces to victory in the American Revolutionary War and served as president of the Constitutional Convention of 1787, which created and ratified the Constitution of the United States and the American federal government. Washington has been called the "Father of his Country" for his manifold leadership in the nation's founding.

Washington's first public office, from 1749 to 1750, was as surveyor of Culpeper County, Virginia. He subsequently received his first military training and was assigned command of the Virginia Regiment during the French and Indian War. He was later elected to the Virginia House of Burgesses and was named a delegate to the Continental Congress, where he was appointed Commanding General of the Continental Army and led American forces allied with France to victory over the British at the Siege of Yorktown in 1781 during the Revolutionary War, paving the way for American independence. He resigned his commission in 1783 after the Treaty of Paris was signed.

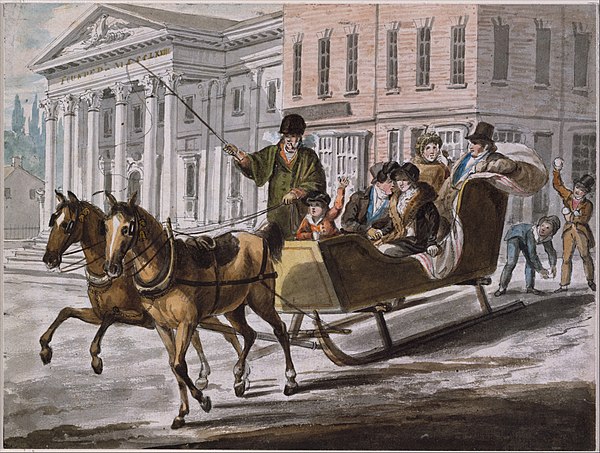

Washington played an indispensable role in adopting and ratifying the Constitution of the United States, which replaced the Articles of Confederation in 1789 and remains the world's longest-standing written and codified national constitution to this day. He was then twice elected president by the Electoral College unanimously. As the first U.S. president, Washington implemented a strong, well-financed national government while remaining impartial in a fierce rivalry that emerged between cabinet members Thomas Jefferson and Alexander Hamilton. During the French Revolution, he proclaimed a policy of neutrality while sanctioning the Jay Treaty. He set enduring precedents for the office of president, including use of the title "Mr. President" and taking an Oath of Office with his hand on a Bible. His Farewell Address on September 19, 1796, is widely regarded as a preeminent statement on republicanism.