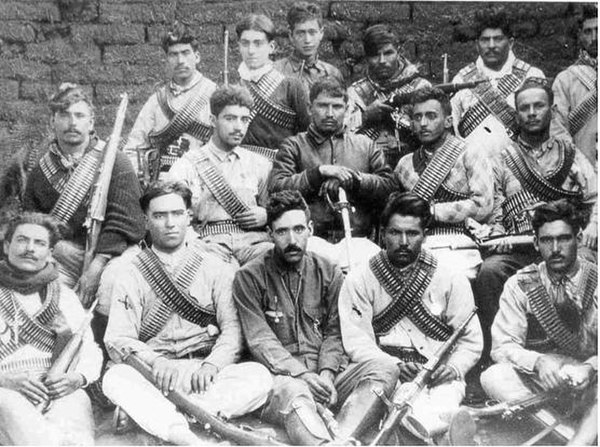

The Mexican Revolution was an extended sequence of armed regional conflicts in Mexico from approximately 1910 to 1920. It has been called "the defining event of modern Mexican history". It resulted in the destruction of the Federal Army and its replacement by a revolutionary army, and the transformation of Mexican culture and government. The northern Constitutionalist faction prevailed on the battlefield and drafted the present-day Constitution of Mexico, which aimed to create a strong central government. Revolutionary generals held power from 1920 to 1940. The revolutionary conflict was primarily a civil war, but foreign powers, having important economic and strategic interests in Mexico, figured in the outcome of Mexico's power struggles; the United States involvement was particularly high. The conflict led to the deaths of around three million people, mostly combatants.

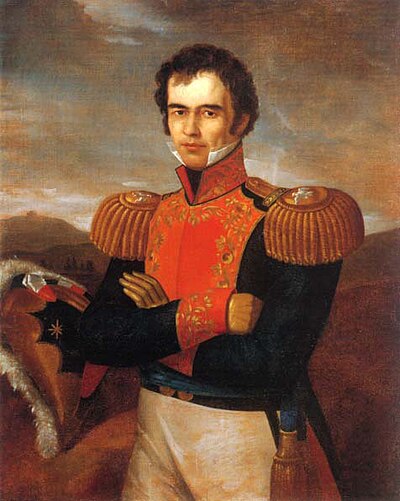

Although the decades-long regime of President Porfirio Díaz (1876–1911) was increasingly unpopular, there was no foreboding in 1910 that a revolution was about to break out. The aging Díaz failed to find a controlled solution to presidential succession, resulting in a power struggle among competing elites and the middle classes, which occurred during a period of intense labor unrest, exemplified by the Cananea and Río Blanco strikes. When wealthy northern landowner Francisco I. Madero challenged Díaz in the 1910 presidential election and Díaz jailed him, Madero called for an armed uprising against Díaz in the Plan of San Luis Potosí. Rebellions broke out first in Morelos, and then to a much greater extent in northern Mexico. The Federal Army was unable to suppress the widespread uprisings, showing the military's weakness and encouraging the rebels. Díaz resigned in May 1911 and went into exile, an interim government was installed until elections could be held, the Federal Army was retained, and revolutionary forces demobilized. The first phase of the Revolution was relatively bloodless and short-lived.

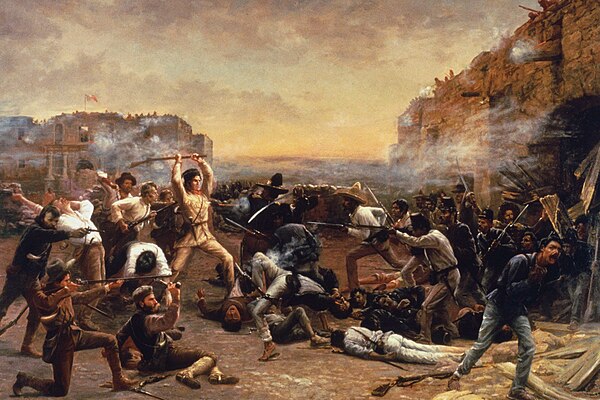

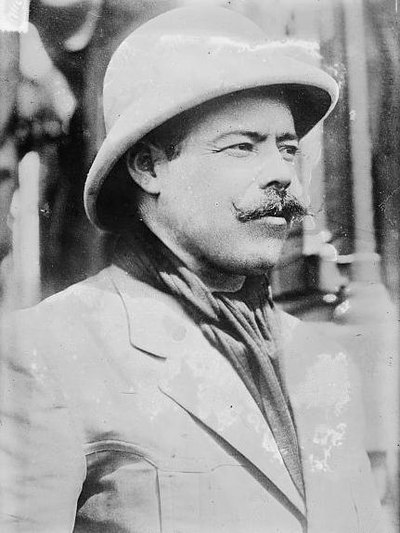

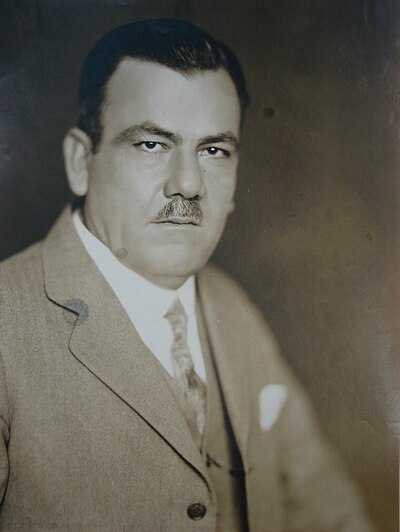

Madero was elected President, taking office in November 1911. He immediately faced the armed rebellion of Emiliano Zapata in Morelos, where peasants demanded rapid action on agrarian reform. Politically inexperienced, Madero's government was fragile, and further regional rebellions broke out. In February 1913, prominent army generals from the Díaz regime staged a coup d'etat in Mexico City, forcing Madero and Vice President Pino Suárez to resign. Days later, both men were assassinated by orders of the new President, Victoriano Huerta. This initiated a new and bloody phase of the Revolution, as a coalition of northerners opposed to the counter-revolutionary regime of Huerta, the Constitutionalist Army led by Governor of Coahuila Venustiano Carranza, entered the conflict. Zapata's forces continued their armed rebellion in Morelos. Huerta's regime lasted from February 1913 to July 1914, and saw the Federal Army defeated by revolutionary armies. The revolutionary armies then fought each other, with the Constitutionalist faction under Carranza defeating the army of former ally Francisco "Pancho" Villa by the summer of 1915.

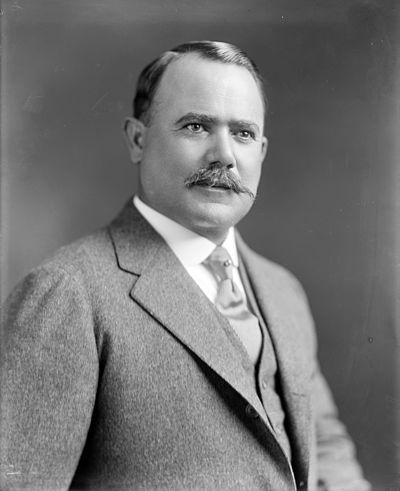

Carranza consolidated power, and a new constitution was promulgated in February 1917. The Mexican Constitution of 1917 established universal male suffrage, promoted secularism, workers' rights, economic nationalism, and land reform, and enhanced the power of the federal government. Carranza became President of Mexico in 1917, serving a term ending in 1920. He attempted to impose a civilian successor, prompting northern revolutionary generals to rebel. Carranza fled Mexico City and was killed. From 1920 to 1940, revolutionary generals held office, a period when State power became more centralized and revolutionary reforms were implemented, bringing the military under the control of the civilian government. The Revolution was a decade-long civil war, with new political leadership that gained power and legitimacy through their participation in revolutionary conflicts. The political party they founded, which would become the Institutional Revolutionary Party, ruled Mexico until the presidential election of 2000. Even the conservative winner of that election, Vicente Fox, contended his election was heir to the 1910 democratic election of Francisco Madero, thereby claiming the heritage and legitimacy of the Revolution.