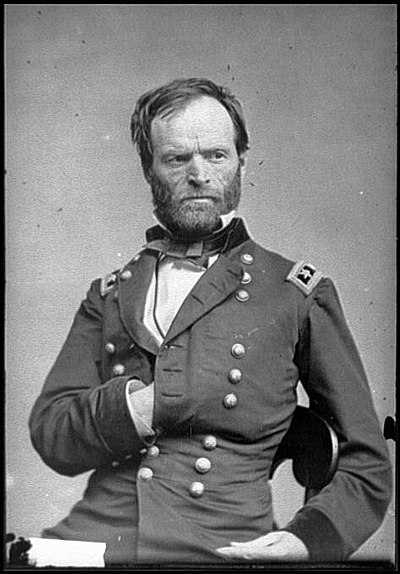

In January 1863, the Army of the Potomac, following the Battle of Fredericksburg and the humiliating Mud March, suffered from rising desertions and plunging morale. Lincoln tried a fifth time with a new general on January 25, 1863—Maj. Gen. Joseph Hooker, a man with a pugnacious reputation who had performed well in previous subordinate commands. [56]

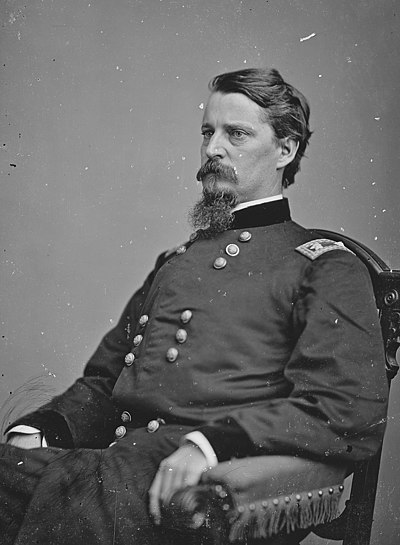

Hooker embarked on a much-needed reorganization of the army, doing away with Burnside's grand division system, which had proved unwieldy; he also no longer had sufficient senior officers on hand that he could trust to command multi-corps operations.[57] He organized the cavalry into a separate corps under the command of Brig. Gen. George Stoneman. But while he concentrated the cavalry into a single organization, he dispersed his artillery battalions to the control of the infantry division commanders, removing the coordinating influence of the army's artillery chief, Brig. Gen. Henry J. Hunt. Among his changes were fixes to the daily diet of the troops, camp sanitary changes, improvements and accountability of the quartermaster system, addition of and monitoring of company cooks, several hospital reforms, an improved furlough system, orders to stem rising desertion, improved drills, and stronger officer training.

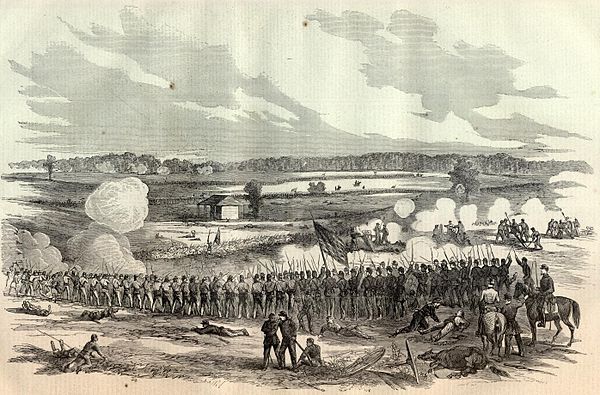

The two armies faced off against each other at Fredericksburg during the winter of 1862–1863. The Chancellorsville campaign began when Hooker secretly moved the bulk of his army up the left bank of the Rappahannock River, then crossed it on the morning of April 27, 1863. Union cavalry under Maj. Gen. George Stoneman began a long-distance raid against Lee's supply lines at about the same time. Crossing the Rapidan River via Germanna and Ely's Fords, the Federal infantry concentrated near Chancellorsville on April 30. Combined with the Union force facing Fredericksburg, Hooker planned a double envelopment, attacking Lee from both his front and rear.

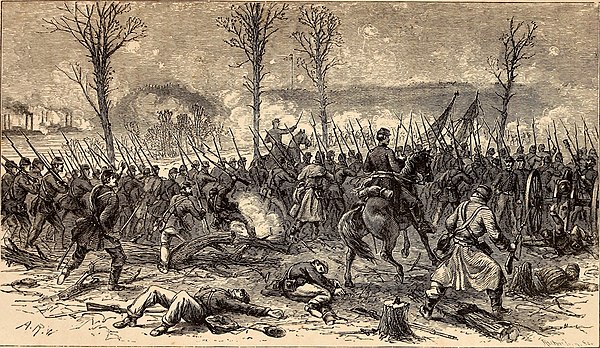

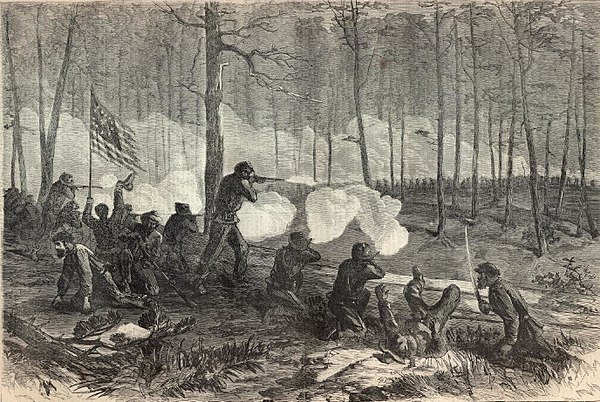

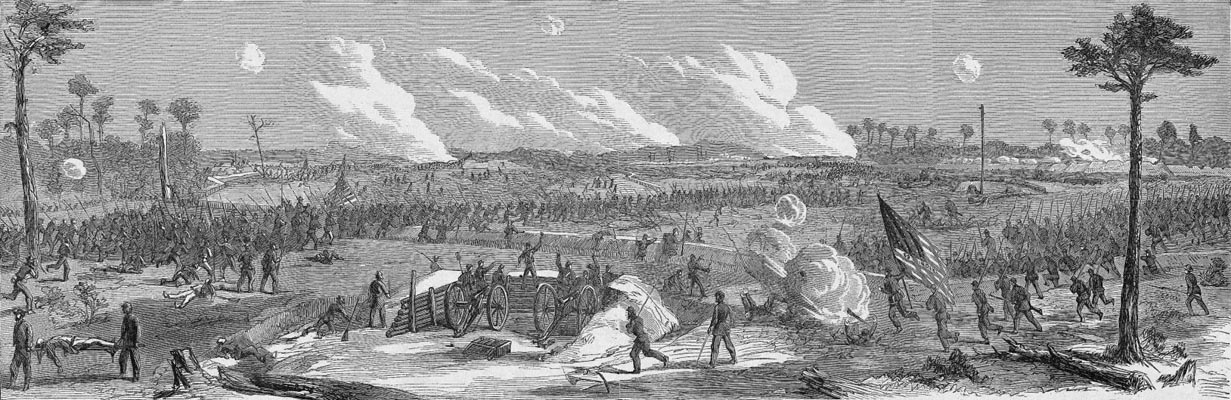

On May 1, Hooker advanced from Chancellorsville toward Lee, but the Confederate general split his army in the face of superior numbers, leaving a small force at Fredericksburg to deter Maj. Gen. John Sedgwick from advancing, while he attacked Hooker's advance with about four-fifths of his army. Despite the objections of his subordinates, Hooker withdrew his men to the defensive lines around Chancellorsville, ceding the initiative to Lee. On May 2, Lee divided his army again, sending Stonewall Jackson's entire corps on a flanking march that routed the Union XI Corps.

The fiercest fighting of the battle—and the second bloodiest day of the Civil War—occurred on May 3 as Lee launched multiple attacks against the Union position at Chancellorsville, resulting in heavy losses on both sides and the pulling back of Hooker's main army. That same day, Sedgwick advanced across the Rappahannock River, defeated the small Confederate force at Marye's Heights in the Second Battle of Fredericksburg, and then moved to the west. The Confederates fought a successful delaying action at the Battle of Salem Church. On the 4th Lee turned his back on Hooker and attacked Sedgwick, and drove him back to Banks' Ford, surrounding them on three sides. Sedgwick withdrew across the ford early on May 5. Lee turned back to confront Hooker who withdrew the remainder of his army across U.S. Ford the night of May 5–6.

Chancellorsville is known as Lee's "perfect battle"[58] because his risky decision to divide his army in the presence of a much larger enemy force resulted in a significant Confederate victory. The victory, a product of Lee's audacity and Hooker's timid decision-making, was tempered by heavy casualties, including Lt. Gen. Thomas J. "Stonewall" Jackson. Jackson was hit by friendly fire, requiring his left arm to be amputated. He died of pneumonia eight days later, a loss that Lee likened to losing his right arm.