History of Japan

The history of Japan dates back to the Paleolithic period, around 38-39,000 years ago,[1] with the first human inhabitants being the Jōmon people, who were hunter-gatherers.[2] The Yayoi people migrated to Japan around the 3rd century BCE,[3] introducing iron technology and agriculture, leading to rapid population growth and ultimately overpowering the Jōmon. The first written reference to Japan was in the Chinese Book of Han in the first century CE. Between the fourth and ninth centuries, Japan transitioned from being a land of many tribes and kingdoms to a unified state, nominally controlled by the Emperor, a dynasty that persists to this day in a ceremonial role.

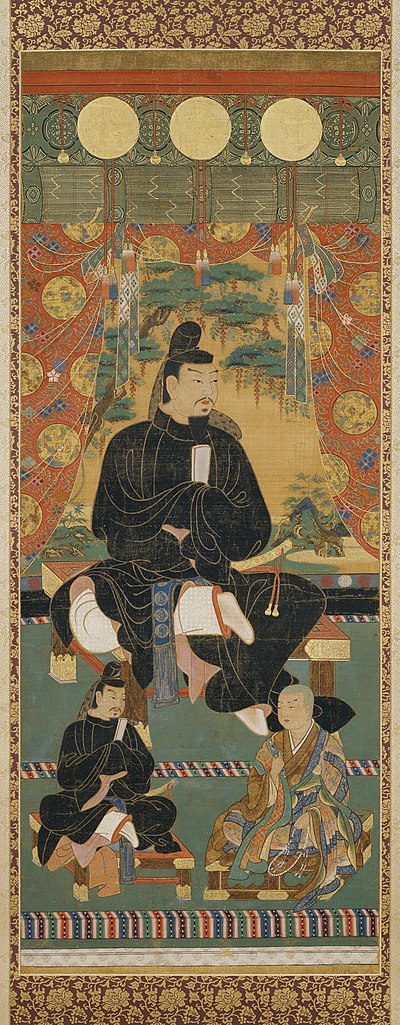

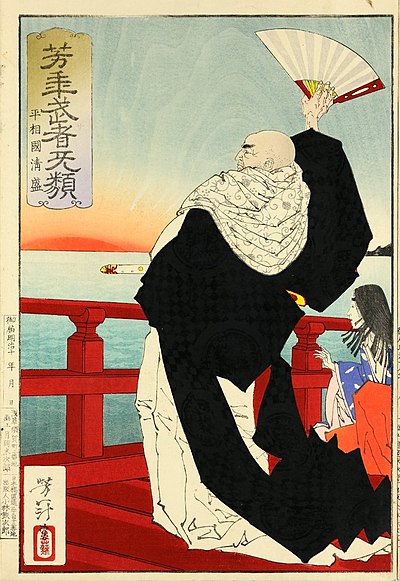

The Heian period (794-1185) marked a high point in classical Japanese culture and saw a blend of native Shinto practices and Buddhism in religious life. Subsequent periods saw the diminishing power of the imperial house and the rise of aristocratic clans like the Fujiwara and military clans of samurai. The Minamoto clan emerged victorious in the Genpei War (1180–85), leading to the establishment of the Kamakura shogunate. This period was characterized by the military rule of the shōgun, with the Muromachi period following the Kamakura shogunate's downfall in 1333. Regional warlords, or daimyō, grew more powerful, eventually causing Japan to enter a period of civil war.

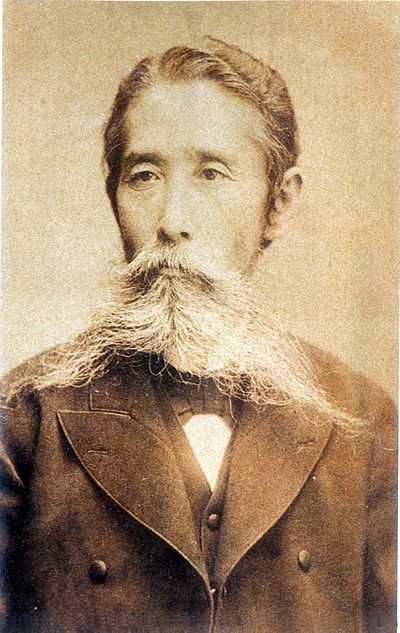

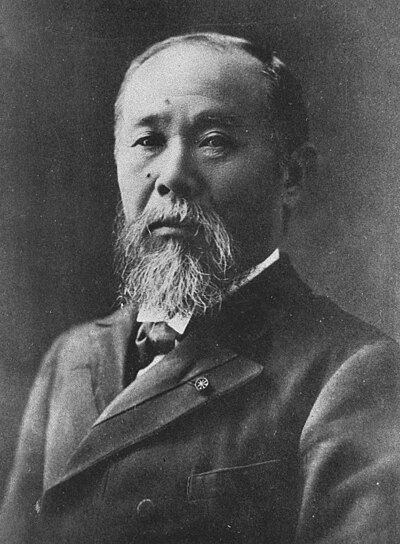

By the late 16th century, Japan was reunified under Oda Nobunaga and his successor Toyotomi Hideyoshi. The Tokugawa shogunate took over in 1600, ushering in the Edo period, a time of internal peace, strict social hierarchy, and isolation from the outside world. European contact began with the arrival of the Portuguese in 1543, who introduced firearms, followed by the American Perry Expedition in 1853-54 that ended Japan’s isolation. The Edo period came to an end in 1868, leading to the Meiji period where Japan modernized along Western lines, becoming a great power.

Japan’s militarization increased in the early 20th century, with invasions into Manchuria in 1931 and China in 1937. The attack on Pearl Harbor in 1941 led to war with the United States and its allies. Despite severe setbacks from Allied bombings and the atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, Japan surrendered only after the Soviet invasion of Manchuria on August 15, 1945. Japan was occupied by Allied forces until 1952, during which time a new constitution was enacted, converting the nation into a constitutional monarchy.

Post-occupation, Japan experienced rapid economic growth, especially after 1955 under the governance of the Liberal Democratic Party, becoming a global economic powerhouse. However, since the economic stagnation known as the "Lost Decade" of the 1990s, growth has slowed. Japan remains a significant player on the global stage, balancing its rich cultural history with its modern achievements.