Civil Rights Movement

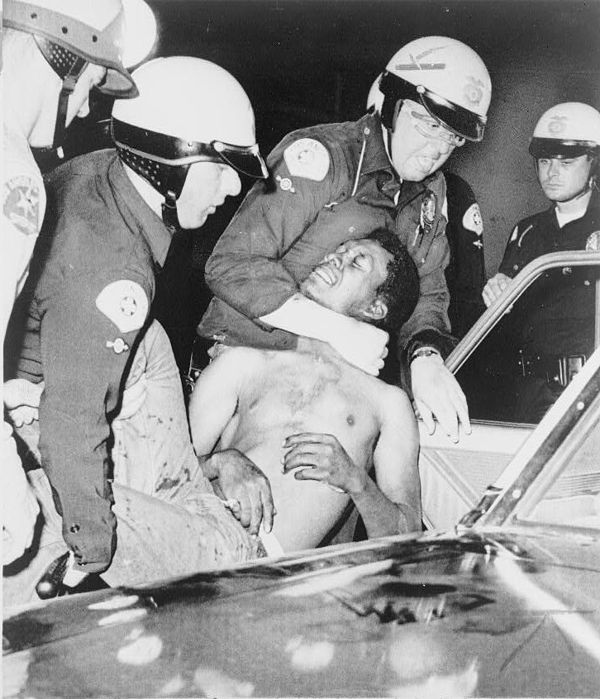

The civil rights movement was a social movement in the United States that sought to end racial segregation and discrimination against African Americans. The movement began in the 1950s and lasted through the 1960s. It sought to achieve full legal equality for African Americans by eliminating segregation and discrimination in all areas of public life. It also sought to end economic, educational, and social inequality for African Americans.

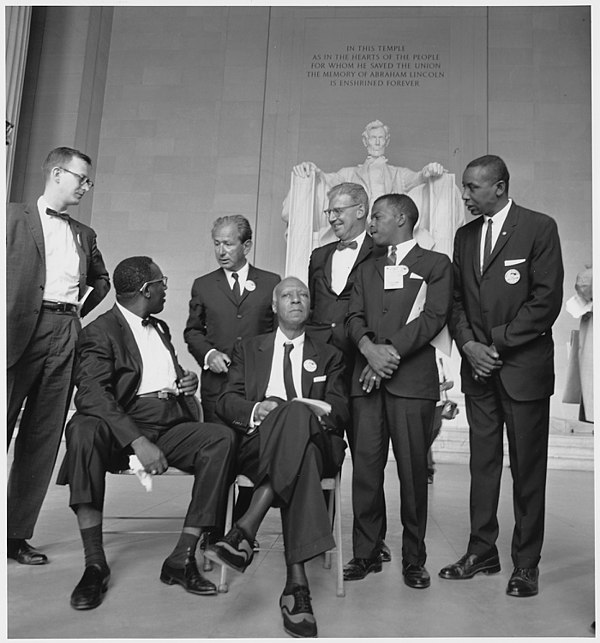

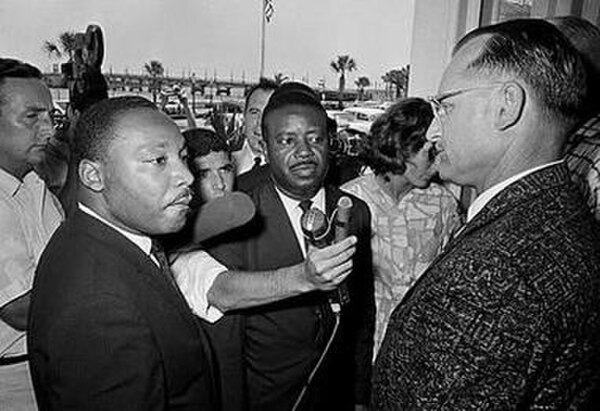

The civil rights movement was led by various organizations and people, including the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP), the Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC), and Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. The movement used peaceful protests, legal action, and civil disobedience to challenge segregation and discrimination. The movement achieved major victories, such as the passage of the Civil Rights Act of 1964, which outlawed segregation in public places, and the Voting Rights Act of 1965, which protected the right of African Americans to vote.

The civil rights movement also contributed to the growth of the Black Power movement, which sought to empower African Americans and gain greater control over their own lives. The civil rights movement was successful in achieving its goals and helped to ensure full legal equality for African Americans.