History of Canada

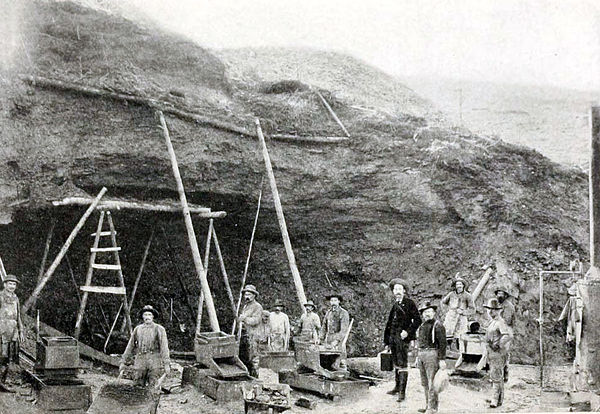

The history of Canada covers the period from the arrival of the Paleo-Indians to North America thousands of years ago to the present day. Prior to European colonization, the lands encompassing present-day Canada were inhabited for millennia by Indigenous peoples, with distinct trade networks, spiritual beliefs, and styles of social organization. Some of these older civilizations had long faded by the time of the first European arrivals and have been discovered through archeological investigations.

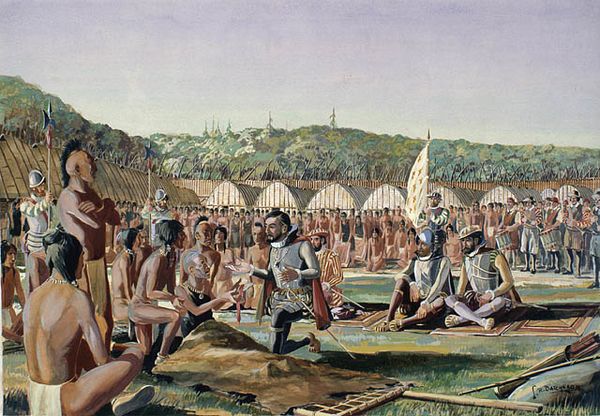

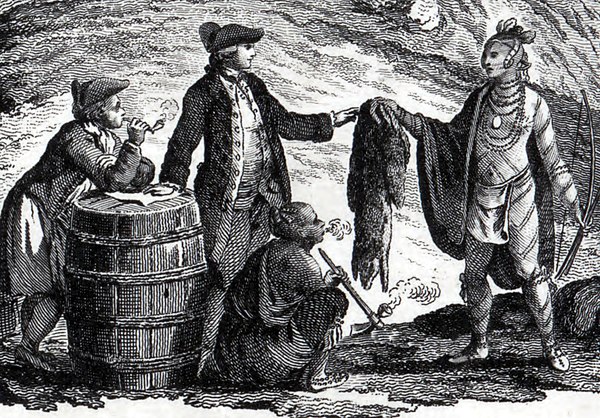

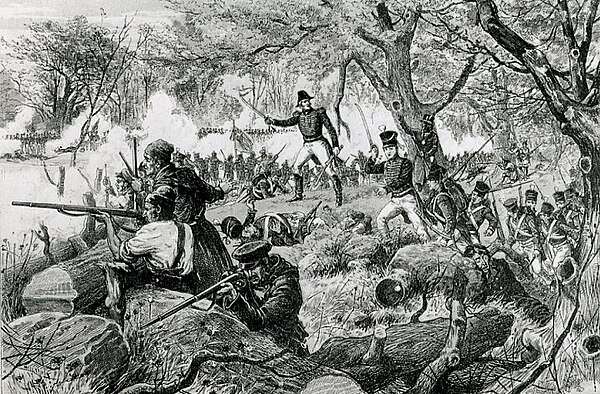

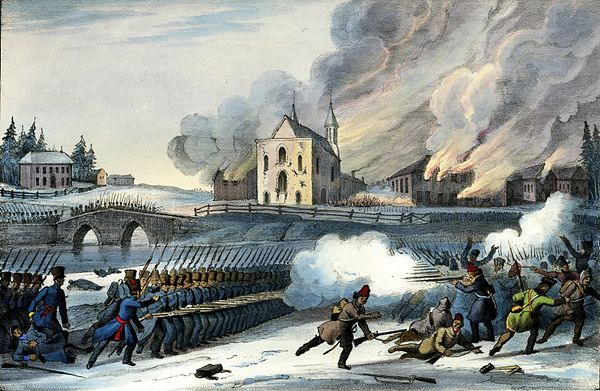

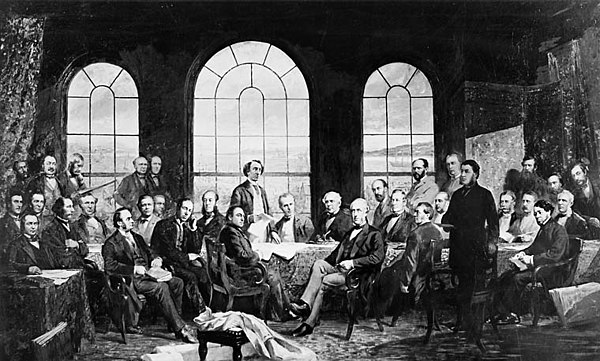

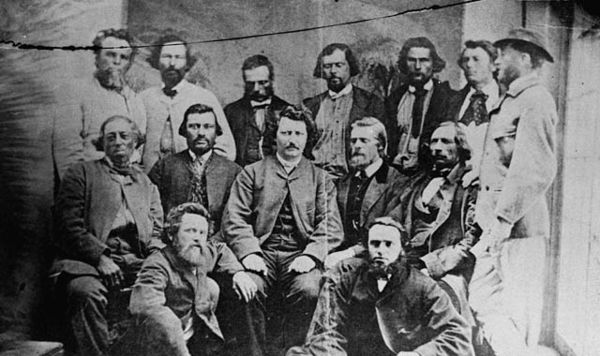

From the late 15th century, French and British expeditions explored, colonized, and fought over various places within North America in what constitutes present-day Canada. The colony of New France was claimed in 1534 with permanent settlements beginning in 1608. France ceded nearly all its North American possessions to the United Kingdom in 1763 at the Treaty of Paris after the Seven Years' War. The now British Province of Quebec was divided into Upper and Lower Canada in 1791. The two provinces were united as the Province of Canada by the Act of Union 1840, which came into force in 1841. In 1867, the Province of Canada was joined with two other British colonies of New Brunswick and Nova Scotia through Confederation, forming a self-governing entity. "Canada" was adopted as the legal name of the new country and the word "Dominion" was conferred as the country's title. Over the next eighty-two years, Canada expanded by incorporating other parts of British North America, finishing with Newfoundland and Labrador in 1949.

Although responsible government had existed in British North America since 1848, Britain continued to set its foreign and defence policies until the end of the First World War. The Balfour Declaration of 1926, the 1930 Imperial Conference and the passing of the Statute of Westminster in 1931 recognized that Canada had become co-equal with the United Kingdom. The Patriation of the Constitution in 1982, marked the removal of legal dependence on the British parliament. Canada currently consists of ten provinces and three territories and is a parliamentary democracy and a constitutional monarchy.

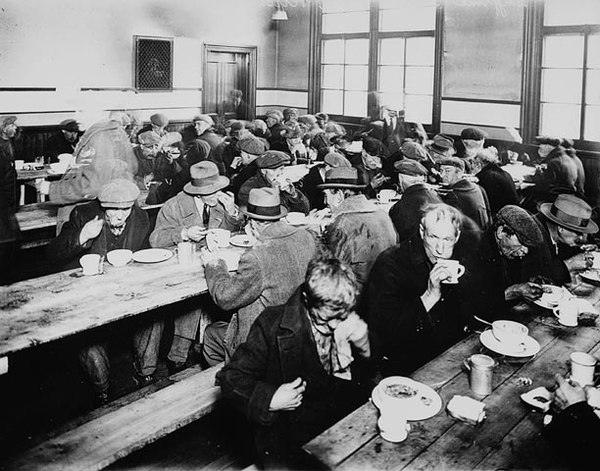

Over centuries, elements of Indigenous, French, British and more recent immigrant customs have combined to form a Canadian culture that has also been strongly influenced by its linguistic, geographic and economic neighbour, the United States. Since the conclusion of the Second World War, Canadians have supported multilateralism abroad and socioeconomic development.