History of California

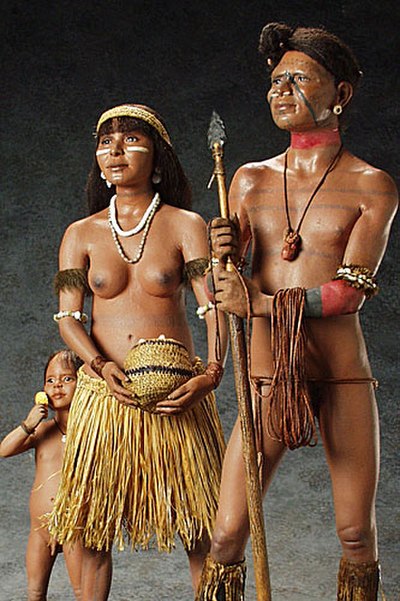

The history of California can be divided into the Native American period (about 10,000 years ago until 1542), the European exploration period (1542–1769), the Spanish colonial period (1769–1821), the Mexican Republic period (1823–1848), and United States statehood (September 9, 1850–present). California was one of the most culturally and linguistically diverse areas in pre-Columbian North America. After contact with Spanish explorers, many of the Native Americans died from foreign diseases and genocide campaigns.

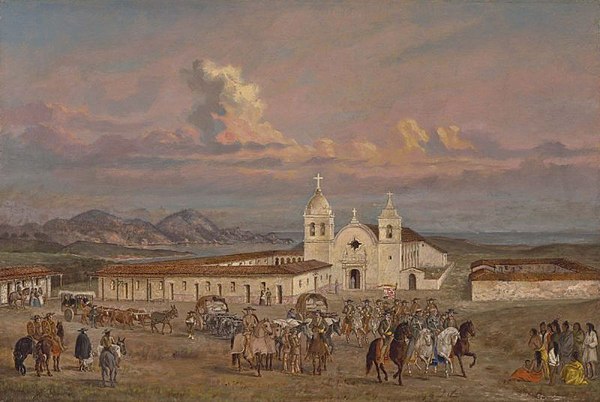

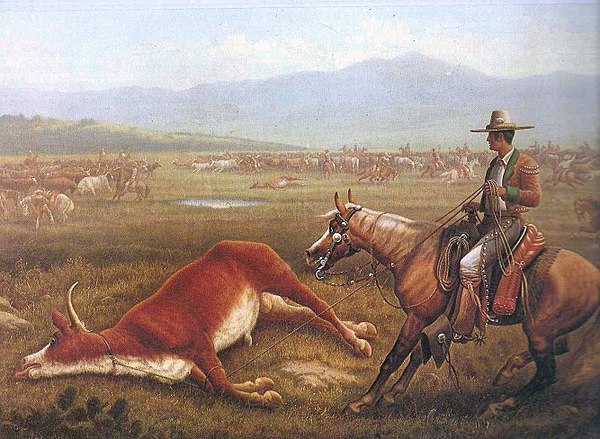

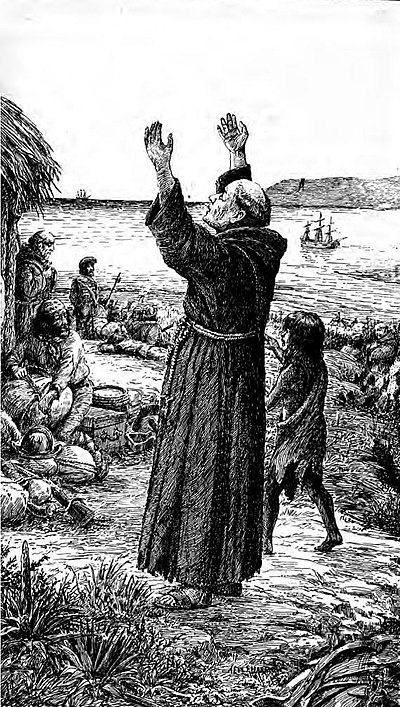

After the Portolá expedition of 1769–1770, Spanish missionaries began setting up 21 California missions on or near the coast of Alta (Upper) California, beginning with the Mission San Diego de Alcala near the location of the modern day city of San Diego, California. During the same period, Spanish military forces built several forts (presidios) and three small towns (pueblos). Two of the pueblos would eventually grow into the cities of Los Angeles and San Jose. After Mexico's Independence was won in 1821, California fell under the jurisdiction of the First Mexican Empire. Fearing the influence of the Roman Catholic church over their newly independent nation, the Mexican government closed all of the missions and nationalized the church's property. They left behind a "Californio" population of several thousand families, with a few small military garrisons. After the Mexican–American War of 1846–1848, The Mexican Republic was forced to relinquish any claim to California to the United States.

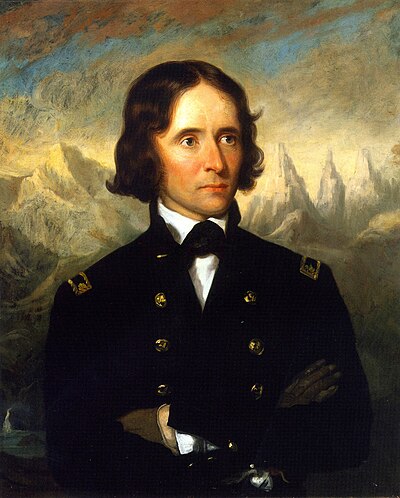

The California Gold Rush of 1848–1855 attracted hundreds of thousands of ambitious young people from around the world. Only a few struck it rich, and many returned home disappointed. Most appreciated the other economic opportunities in California, especially in agriculture, and brought their families to join them. California became the 31st U.S. state in the Compromise of 1850 and played a small role in the American Civil War. Chinese immigrants increasingly came under attack from nativists; they were forced out of industry and agriculture and into Chinatowns in the larger cities. As gold petered out, California increasingly became a highly productive agricultural society. The coming of the railroads in 1869 linked its rich economy with the rest of the nation, and attracted a steady stream of settlers. In the late 19th century, Southern California, especially Los Angeles, started to grow rapidly.