Korean War

The Korean War took place between North Korea and South Korea from 1950 to 1953. It started on June 25 1950 with North Koreas invasion of South Korea. Ended after an armistice, on July 27 1953. China and the Soviet Union supported the North while United Nations (UN) forces led by the United States supported the South.

After World War II ended in 1945 Korea, which had been under rule for 35 years was divided temporarily by the United States and the Soviet Union along the parallel. Due to Cold War tensions each part eventually became a state. Kim Il Sung led North Korea and Syngman Rhee led the First Republic of Korea in the south. Both claimed to be the government of all of Korea and neither accepted the division at the parallel as permanent.

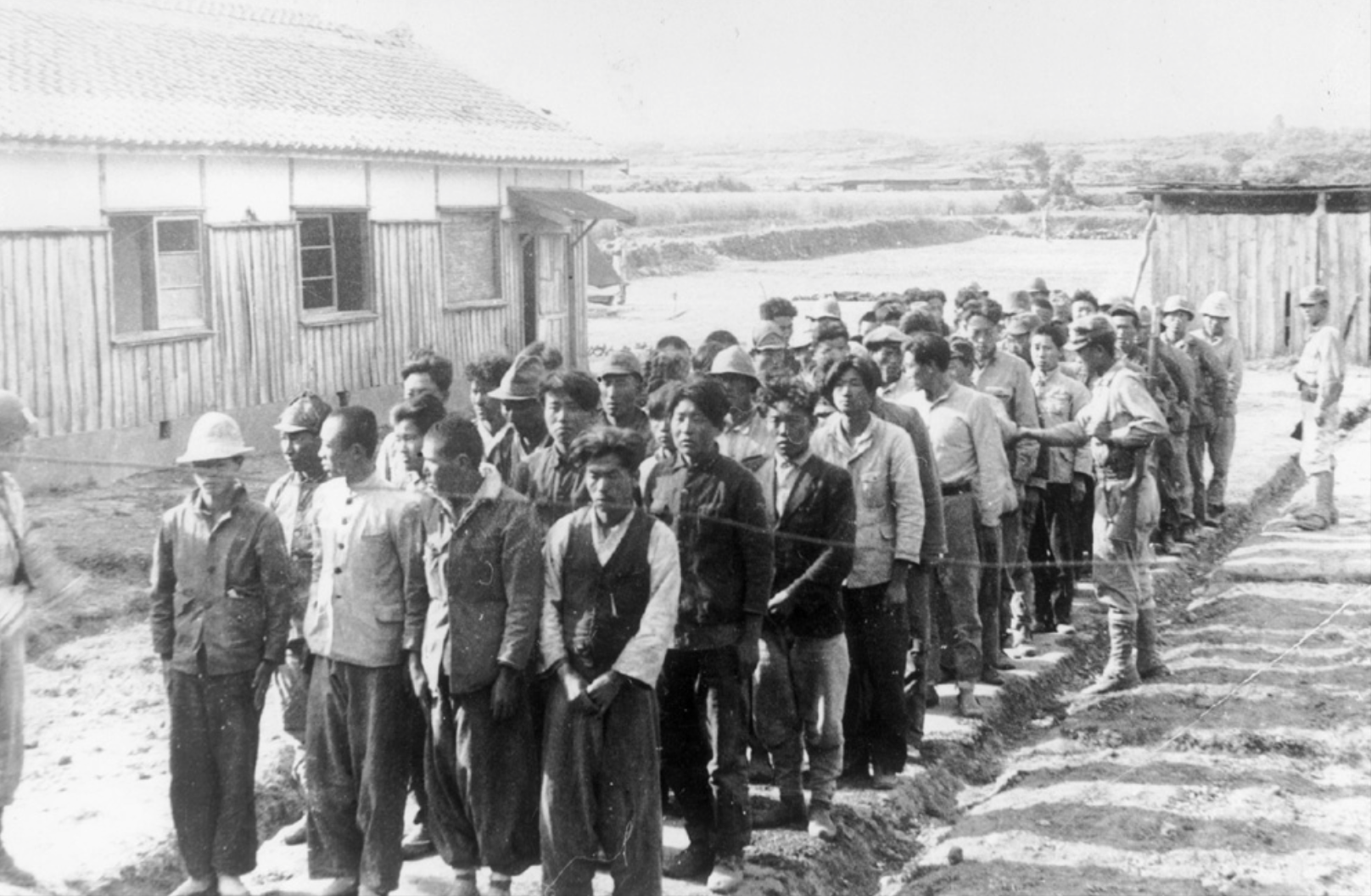

There were conflicts along their borders; additionally South Korea quelled an uprising in Jeju from April 1948 to May 1949 with alleged support, from Pyongyang. On June 25 1950 North Koreas Korean Peoples Army (KPA) crossed below the parallel.

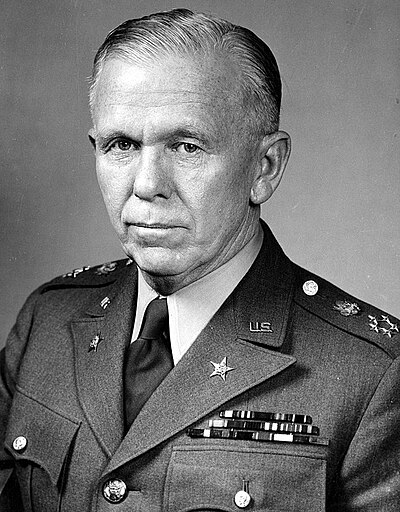

After the Soviet Unions absence the United Nations Security Council condemned the attack. Advised nations to push the KPA under the United Nations Command. UN forces comprised twenty one countries with the United States contributing 90% of personnel.

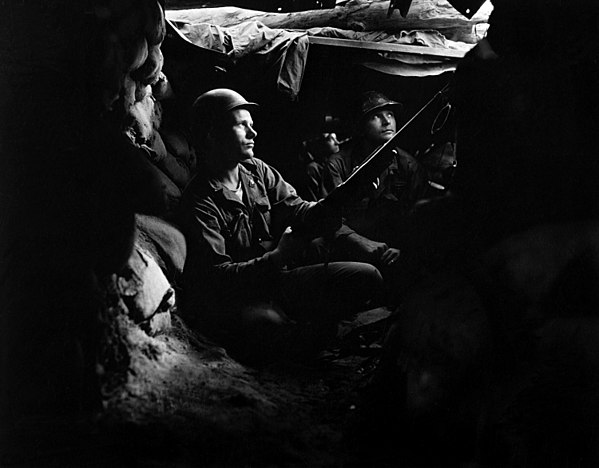

Following two months of conflict the Korean army (ROKA) and its allies were close to defeat holding on within the Pusan Perimeter. In September 1950 UN forces made a landing at Incheon disrupting KPA troops and supply lines. They pushed into North Korea in October 1950. Moved towards the Yalu River bordering China. The Chinese Peoples Volunteer Army (PVA) entered the war on October 19th, 1950 by crossing the Yalu River. After PVAs subsequent offensives UN forces withdrew from North Korea. Communist troops recaptured Seoul in January 1951. Later lost control of it again. Following a failed spring offensive they were pushed back, to the parallel leading to two years of attrition warfare.

The hostilities came to an end on July 27th, 1953 with the signing of the Korean Armistice Agreement permitting prisoner exchanges and establishing a Korean Demilitarized Zone (DMZ).

The war uprooted millions of individuals resulting in 3 million deaths with a percentage of civilian casualties compared to World War II and the Vietnam War. Reported atrocities include the execution of suspected communists, by the government and the mistreatment and starvation of prisoners of war by North Koreans. North Korea endured bombing becoming one of the heavily targeted nations in history. Most major cities, in Korea were left in ruins. The lack of a peace agreement has kept this conflict unresolved and stagnant.