Thirty Years War

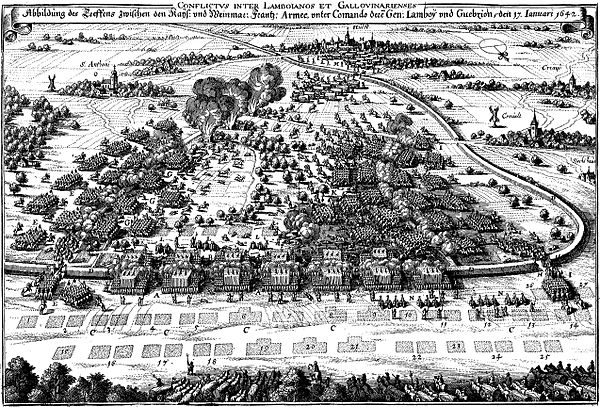

The Thirty Years' War was one of the longest and most destructive conflicts in European history, lasting from 1618 to 1648. Fought primarily in Central Europe, an estimated 4.5 to 8 million soldiers and civilians died as a result of battle, famine, and disease, while some areas of what is now modern Germany experienced population declines of over 50%. Related conflicts include the Eighty Years' War, the War of the Mantuan Succession, the Franco-Spanish War, and the Portuguese Restoration War.

Until the 20th century, historians generally viewed the war as a continuation of the religious struggle initiated by the 16th-century Reformation within the Holy Roman Empire. The 1555 Peace of Augsburg attempted to resolve this by dividing the Empire into Lutheran and Catholic states, but over the next 50 years the expansion of Protestantism beyond these boundaries destabilised the settlement. While most modern commentators accept that differences over religion and Imperial authority were important factors in causing the war, they argue its scope and extent were driven by the contest for European dominance between Habsburg-ruled Spain and Austria, and the French House of Bourbon.

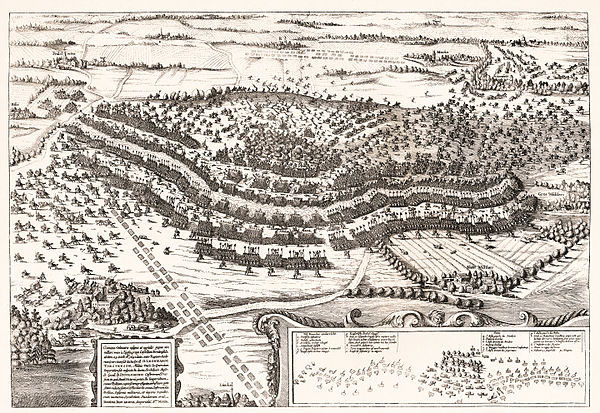

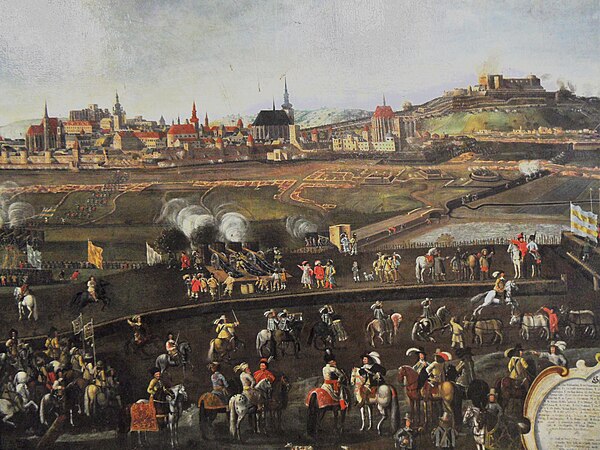

Its outbreak is generally traced to 1618, when Emperor Ferdinand II was deposed as king of Bohemia and replaced by the Protestant Frederick V of the Palatinate. Although Imperial forces quickly suppressed the Bohemian Revolt, his participation expanded the fighting into the Palatinate, whose strategic importance drew in the Dutch Republic and Spain, then engaged in the Eighty Years' War. Since rulers like Christian IV of Denmark and Gustavus Adolphus of Sweden also held territories within the Empire, this gave them and other foreign powers an excuse to intervene, turning an internal dynastic dispute into a broader European conflict.

The first phase from 1618 until 1635 was primarily a civil war between German members of the Holy Roman Empire, with support from external powers. After 1635, the Empire became one theatre in a wider struggle between France, supported by Sweden, and Emperor Ferdinand III, allied with Spain. This concluded with the 1648 Peace of Westphalia, whose provisions included greater autonomy within the Empire for states like Bavaria and Saxony, as well as acceptance of Dutch independence by Spain. By weakening the Habsburgs relative to France, the conflict altered the European balance of power and set the stage for the wars of Louis XIV.