War of 1812

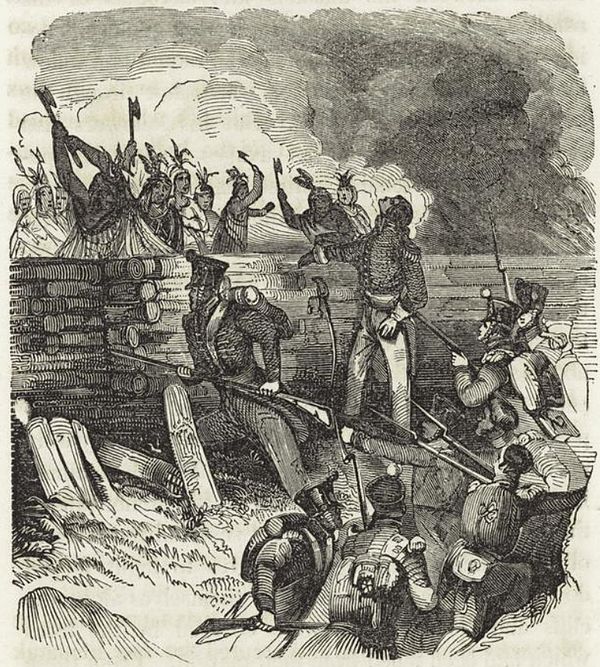

The War of 1812 was a conflict fought between the United States and its allies, and the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland and its dependent colonies in North America and its allies. Many native peoples fought in the war on both sides.

Tensions originated in long-standing differences over territorial expansion in North America and British support for Native American tribes who opposed US colonial settlement in the Northwest Territory. These escalated in 1807 after the Royal Navy began enforcing tighter restrictions on American trade with France and press-ganged men they claimed as British subjects, even those with American citizenship certificates.[1] Opinion in the US was split on how to respond, and although majorities in both the House and Senate voted for war, they divided along strict party lines, with the Democratic-Republican Party in favour and the Federalist Party against.[2] News of British concessions made in an attempt to avoid war did not reach the US until late July, by which time the conflict was already underway.

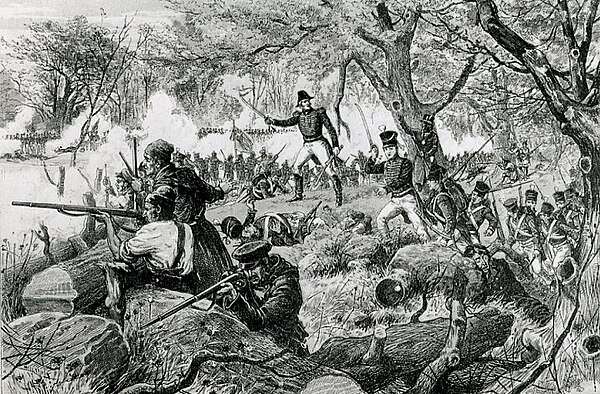

At sea, the far larger Royal Navy imposed an effective blockade on U.S. maritime trade, while between 1812 to 1814 British regulars and colonial militia defeated a series of American attacks on Upper Canada.[3] This was balanced by the US winning control of the Northwest Territory with victories at Lake Erie and the Thames in 1813. The abdication of Napoleon in early 1814 allowed the British to send additional troops to North America and the Royal Navy to reinforce their blockade, crippling the American economy.[4] In August 1814, negotiations began in Ghent, with both sides wanting peace; the British economy had been severely impacted by the trade embargo, while the Federalists convened the Hartford Convention in December to formalise their opposition to the war.

In August 1814, British troops burned Washington, before American victories at Baltimore and Plattsburgh in September ended fighting in the north. Fighting continued in the Southeastern United States, where in late 1813 a civil war had broken out between a Creek faction supported by Spanish and British traders and those backed by the US. Supported by US militia under General Andrew Jackson, the American backed Creeks won a series of victories, culminating in the capture of Pensacola in November 1814. In early 1815, Jackson defeated a British attack on New Orleans, catapulting him to national celebrity and later victory in the 1828 United States presidential election. News of this success arrived in Washington at the same time as that of the signing of the Treaty of Ghent, which essentially restored the position to that prevailing before the war. While Britain insisted this included lands belonging to their Native American allies prior to 1811, Congress did not recognize them as independent nations and neither side sought to enforce this requirement.