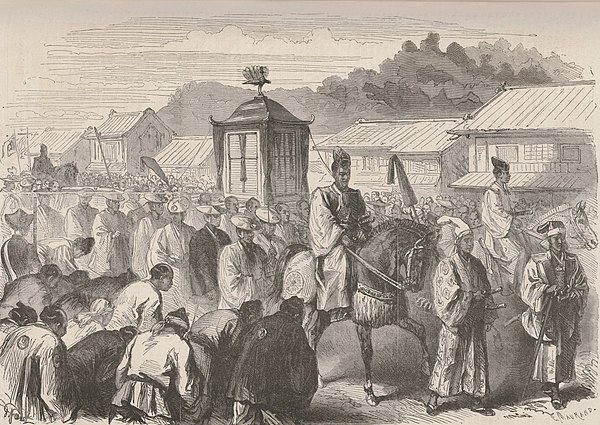

The foreign employees in Meiji Japan, known in Japanese as O-yatoi Gaikokujin, were hired by the Japanese government and municipalities for their specialized knowledge and skill to assist in the modernization of the Meiji period. The term came from Yatoi (a person hired temporarily, a day laborer), was politely applied for hired foreigner as O-yatoi gaikokujin.

The total number is over 2,000, probably reaches 3,000 (with thousands more in the private sector). Until 1899, more than 800 hired foreign experts continued to be employed by the government, and many others were employed privately. Their occupation varied, ranging from high salaried government advisors, college professors and instructor, to ordinary salaried technicians.

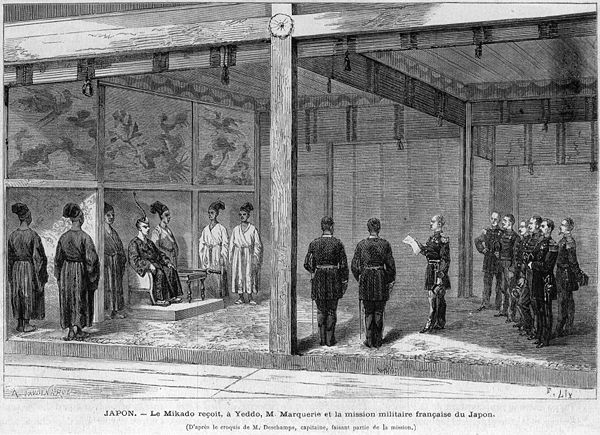

Along the process of the opening of the country, the Tokugawa Shogunate government first hired, German diplomat Philipp Franz von Siebold as diplomatic advisor, Dutch naval engineer Hendrik Hardes for Nagasaki Arsenal and Willem Johan Cornelis, Ridder Huijssen van Kattendijke for Nagasaki Naval Training Center, French naval engineer François Léonce Verny for Yokosuka Naval Arsenal, and British civil engineer Richard Henry Brunton. Most of the O-yatoi was appointed through government approval with two or three years contract, and took their responsibility properly in Japan, except some cases.

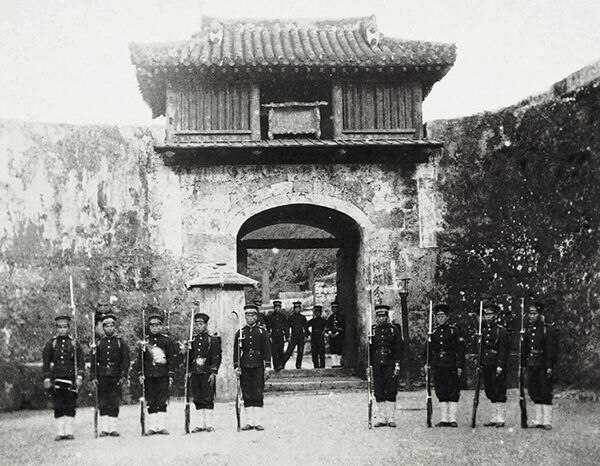

As the Public Works hired almost 40% of the total number of the O-yatois, the main goal in hiring the O-yatois was to obtain transfers of technology and advice on systems and cultural ways. Therefore, young Japanese officers gradually took over the post of the O-yatoi after they completed training and education at the Imperial College, Tokyo, the Imperial College of Engineering or studying abroad.

The O-yatois were highly paid; in 1874, they numbered 520 men, at which time their salaries came to ¥2.272 million, or 33.7 percent of the national annual budget. The salary system was equivalent to the British India, for instance, the chief engineer of the British India's Public Works was paid 2,500 Rs/month which was almost same as 1,000 Yen, salary of Thomas William Kinder, superintendent of the Osaka Mint in 1870.

Despite the value they provided in the modernization of Japan, the Japanese government did not consider it prudent for them to settle in Japan permanently. After the contract terminated, most of them returned to their country except some, like Josiah Conder and William Kinninmond Burton.

The system was officially terminated in 1899 when extraterritoriality came to an end in Japan. Nevertheless, similar employment of foreigners persists in Japan, particularly within the national education system and professional sports.