History of Paris

Between 250 and 225 BCE, the Parisii, a sub-tribe of the Celtic Senones, settled on the banks of the Seine, built bridges and a fort, minted coins, and began to trade with other river settlements in Europe. In 52 BCE, a Roman army led by Titus Labienus defeated the Parisii and established a Gallo-Roman garrison town called Lutetia. The town was Christianised in the 3rd century CE, and after the collapse of the Roman Empire, it was occupied by Clovis I, the King of the Franks, who made it his capital in 508.

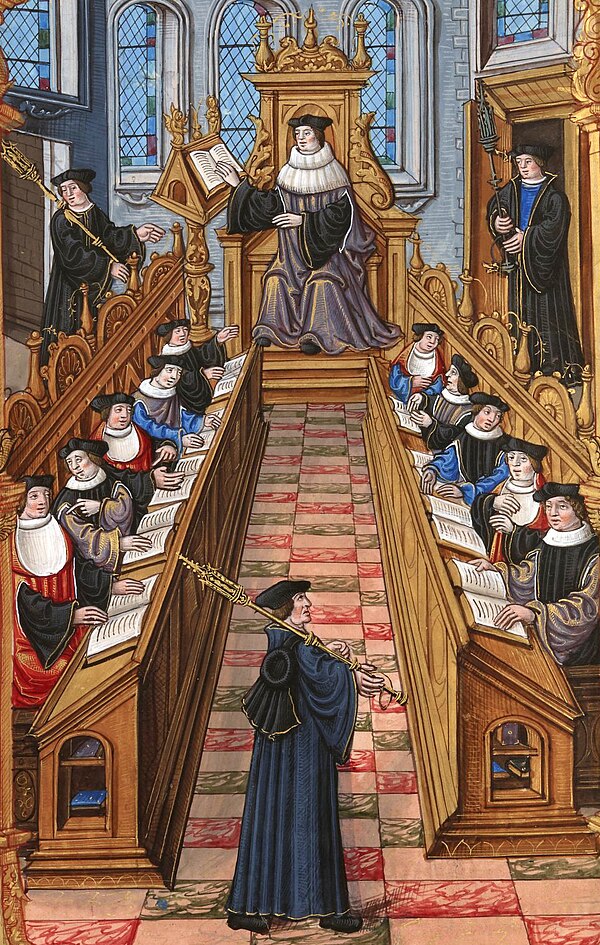

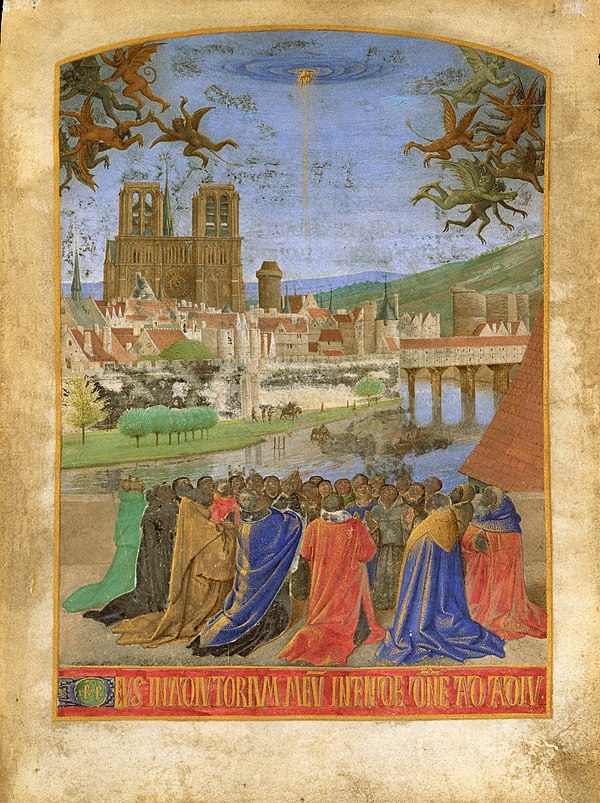

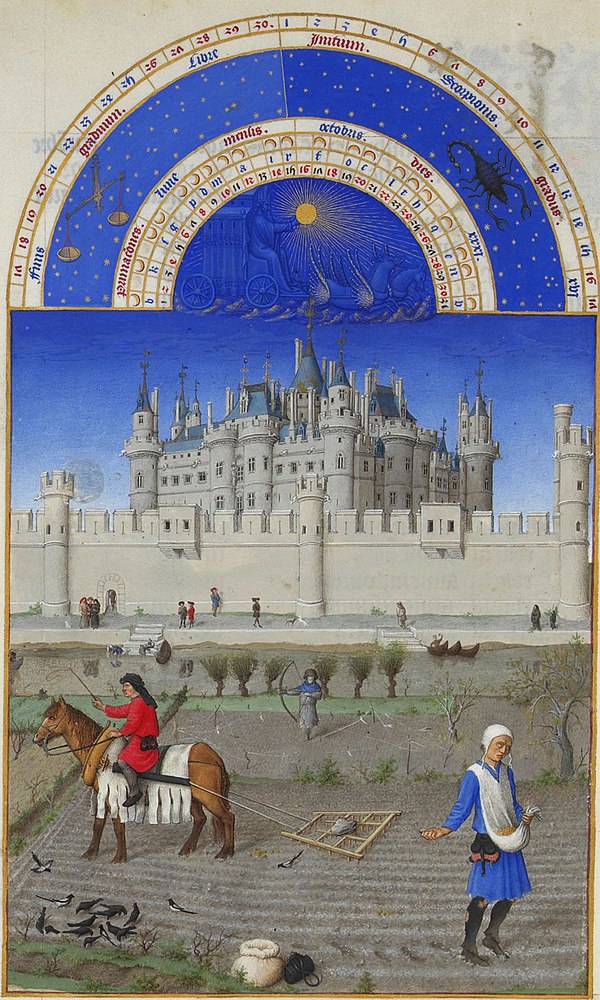

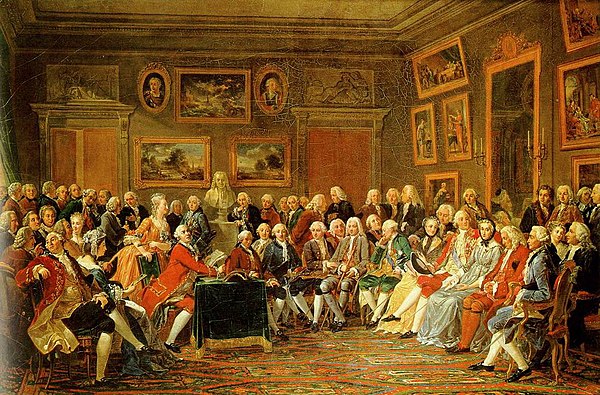

During the Middle Ages, Paris was the largest city in Europe, an important religious and commercial centre, and the birthplace of the Gothic style of architecture. The University of Paris on the Left Bank, organised in the mid-13th century, was one of the first in Europe. It suffered from the Bubonic Plague in the 14th century and the Hundred Years' War in the 15th century, with recurrence of the plague. Between 1418 and 1436, the city was occupied by the Burgundians and English soldiers. In the 16th century, Paris became the book-publishing capital of Europe, though it was shaken by the French Wars of Religion between Catholics and Protestants. In the 18th century, Paris was the centre of the intellectual ferment known as the Enlightenment, and the main stage of the French Revolution from 1789, which is remembered every year on the 14th of July with a military parade.

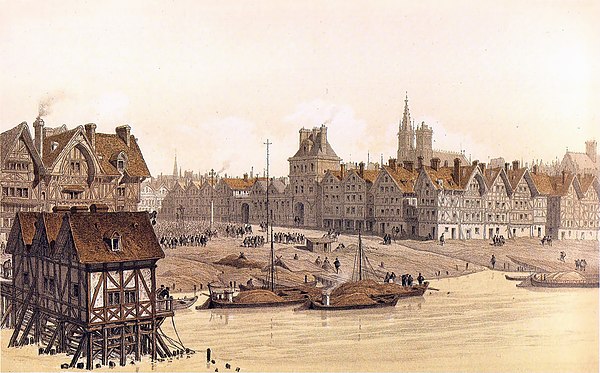

In the 19th century, Napoleon embellished the city with monuments to military glory. It became the European capital of fashion and the scene of two more revolutions (in 1830 and 1848). Under Napoleon III and his Prefect of the Seine, Georges-Eugène Haussmann, the centre of Paris was rebuilt between 1852 and 1870 with wide new avenues, squares and new parks, and the city was expanded to its present limits in 1860. In the latter part of the century, millions of tourists came to see the Paris International Expositions and the new Eiffel Tower.

In the 20th century, Paris suffered bombardment in World War I and German occupation from 1940 until 1944 in World War II. Between the two wars, Paris was the capital of modern art and a magnet for intellectuals, writers and artists from around the world. The population reached its historic high of 2.1 million in 1921, but declined for the rest of the century. New museums (The Centre Pompidou, Musée Marmottan Monet and Musée d'Orsay) were opened, and the Louvre given its glass pyramid.