War of the Sixth Coalition

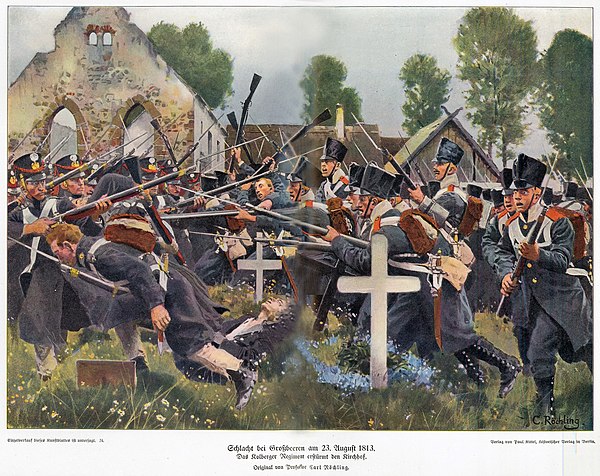

In the War of the Sixth Coalition (March 1813 – May 1814), sometimes known in Germany as the Wars of Liberation, a coalition of Austria, Prussia, Russia, the United Kingdom, Portugal, Sweden, Spain and a number of German States defeated France and drove Napoleon into exile on Elba. After the disastrous French invasion of Russia of 1812 in which they had been forced to support France, Prussia and Austria joined Russia, the United Kingdom, Sweden, Portugal and the rebels in Spain who were already at war with France.

The War of the Sixth Coalition saw major battles at Lützen, Bautzen, and Dresden. The even larger Battle of Leipzig (also known as the Battle of Nations) was the largest battle in European history before World War I. Ultimately, Napoleon's earlier setbacks in Portugal, Spain, and Russia proved to be the seeds of his undoing. With their armies reorganized, the allies drove Napoleon out of Germany in 1813 and invaded France in 1814. The Allies defeated the remaining French armies, occupied Paris, and forced Napoleon to abdicate and go into exile. The French monarchy was revived by the allies, who handed rule to the heir of the House of Bourbon in the Bourbon Restoration.

The "Hundred Days" War of the Seventh Coalition was triggered in 1815 when Napoleon escaped from his captivity on Elba and returned to power in France. He was defeated again for the final time at Waterloo, ending the Napoleonic Wars.