History of Indonesia

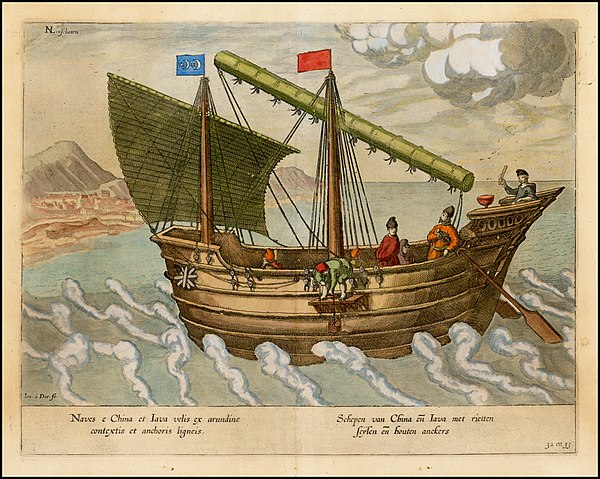

The history of Indonesia has been shaped by geographic position, its natural resources, a series of human migrations and contacts, wars of conquest, the spread of Islam from the island of Sumatra in the 7th century CE and the establishment of Islamic kingdoms. The country's strategic sea-lane position fostered inter-island and international trade; trade has since fundamentally shaped Indonesian history. The area of Indonesia is populated by peoples of various migrations, creating a diversity of cultures, ethnicities, and languages. The archipelago's landforms and climate significantly influenced agriculture and trade, and the formation of states. The boundaries of the state of Indonesia match the 20th-century borders of the Dutch East Indies.

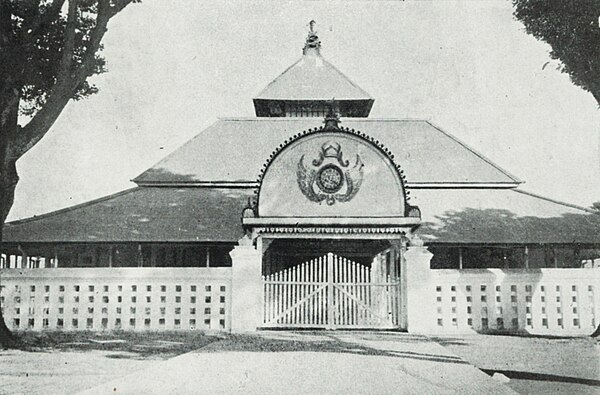

Austronesian people, who form the majority of the modern population, are thought to have originally been from Taiwan and arrived in Indonesia around 2000 BCE. From the 7th century CE, the powerful Srivijaya naval kingdom flourished bringing Hindu and Buddhist influences with it. The agricultural Buddhist Sailendra and Hindu Mataram dynasties subsequently thrived and declined in inland Java. The last significant non-Muslim kingdom, the Hindu Majapahit kingdom, flourished from the late 13th century, and its influence stretched over much of Indonesia. The earliest evidence of Islamised populations in Indonesia dates to the 13th century in northern Sumatra; other Indonesian areas gradually adopted Islam, which became the dominant religion in Java and Sumatra by the end of the 12th century up to of the 16th century. For the most part, Islam overlaid and mixed with existing cultural and religious influences.

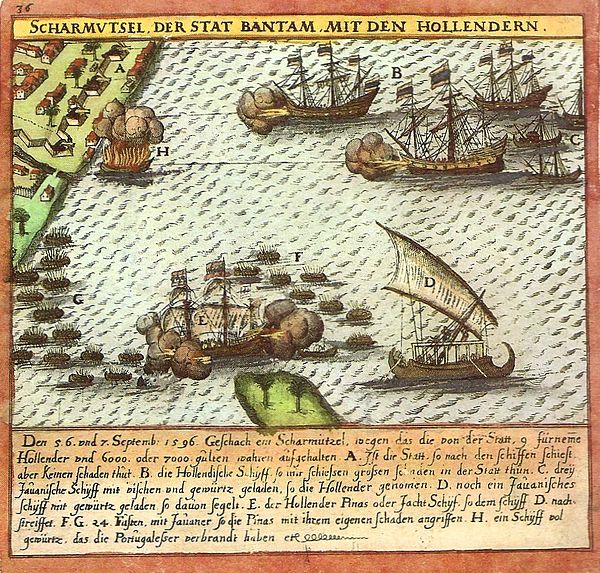

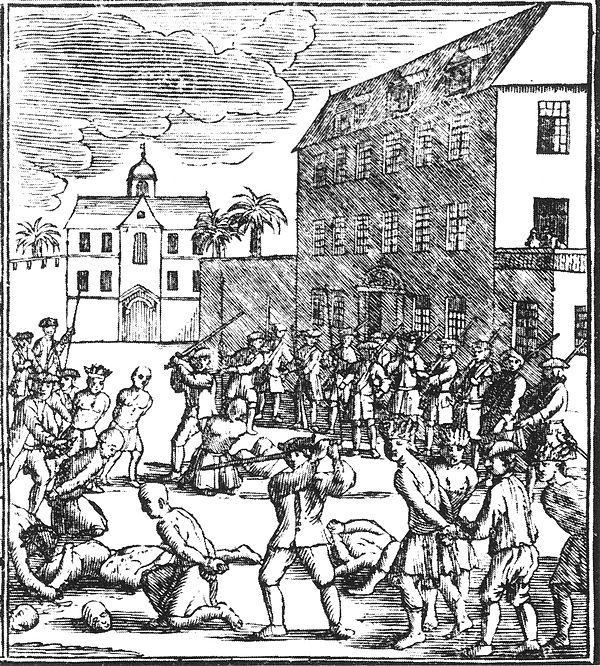

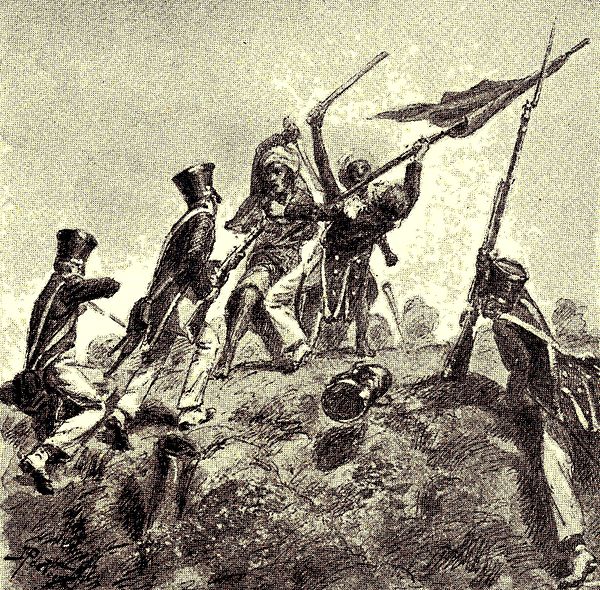

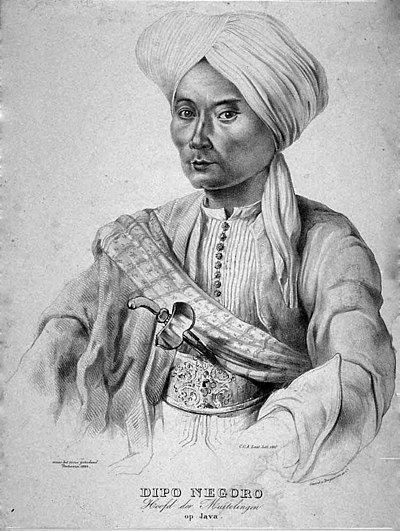

Europeans such as the Portuguese arrived in Indonesia from the 16th century seeking to monopolise the sources of valuable nutmeg, cloves, and cubeb pepper in Maluku. In 1602, the Dutch established the Dutch East India Company (VOC) and became the dominant European power by 1610. Following bankruptcy, the VOC was formally dissolved in 1800, and the government of the Netherlands established the Dutch East Indies under government control. By the early 20th century, Dutch dominance extended to the current boundaries. The Japanese invasion and subsequent occupation in 1942–1945 during World War II ended Dutch rule, and encouraged the previously suppressed Indonesian independence movement. Two days after the surrender of Japan in August 1945, nationalist leader Sukarno declared independence and became president. The Netherlands tried to reestablish its rule, but a bitter armed and diplomatic struggle ended in December 1949, when in the face of international pressure, the Dutch formally recognised Indonesian independence.

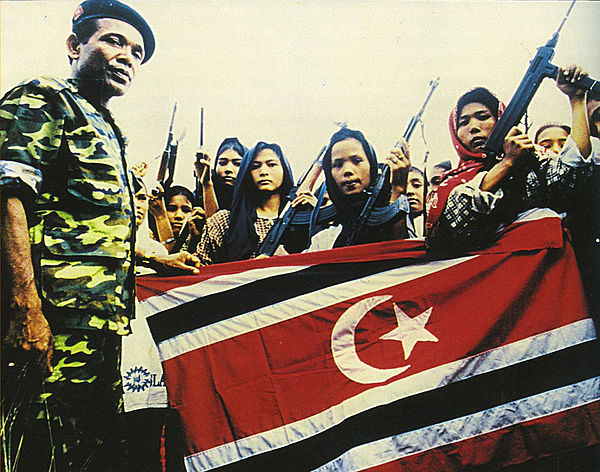

An attempted coup in 1965 led to a violent army-led anti-communist purge in which over half a million people were killed. General Suharto politically outmanoeuvred President Sukarno, and became president in March 1968. His New Order administration garnered the favour of the West, whose investment in Indonesia was a major factor in the subsequent three decades of substantial economic growth. In the late 1990s, however, Indonesia was the country hardest hit by the East Asian Financial Crisis, which led to popular protests and Suharto's resignation on 21 May 1998. The Reformasi era following Suharto's resignation, has led to a strengthening of democratic processes, including a regional autonomy program, the secession of East Timor, and the first direct presidential election in 2004. Political and economic instability, social unrest, corruption, natural disasters, and terrorism have slowed progress. Although relations among different religious and ethnic groups are largely harmonious, acute sectarian discontent and violence remain problems in some areas.