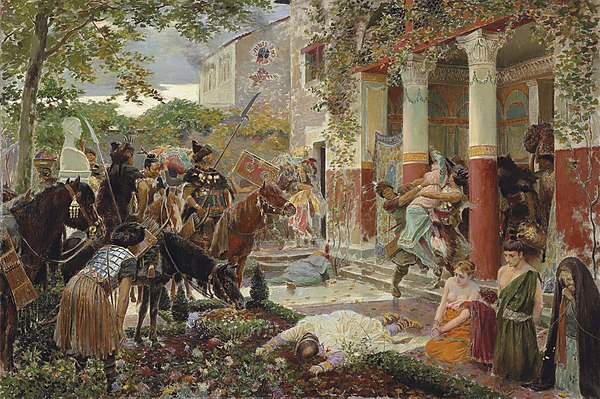

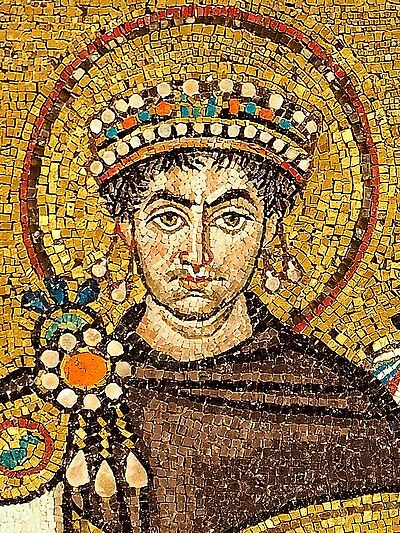

During the later stages of the Gothic War, the Gothic king Teia called upon the Franks for help against the Roman armies under the eunuch Narses. Although King Theudebald refused to send aid, he allowed two of his subjects, the Alemanni chieftains Leutharis and Butilinus, to cross into Italy. According to the historian Agathias, the two brothers gathered a host of 75,000 Franks and Alemanni, and in early 553 crossed the Alps and took the town of Parma. They defeated a force under the Heruli commander Fulcaris, and soon many Goths from northern Italy joined their forces. In the meantime, Narses dispersed his troops to garrisons throughout central Italy, and himself wintered at Rome.

In the spring of 554, the two brothers invaded central Italy, plundering as they descended southwards, until they came to Samnium. There they divided their forces, with Butilinus and the larger part of the army marching south towards Campania and the Strait of Messina, while Leutharis led the remainder towards Apulia and Otranto. Leutharis, however, soon turned back home, laden with spoils. His vanguard, however, was heavily defeated by the Armenian Byzantine Artabanes at Fanum, leaving most of the booty behind. The remainder managed to reach northern Italy and cross the Alps into Frankish territory, but not before losing more men to a plague, including Leutharis himself.

Butilinus, on the other hand, more ambitious and possibly persuaded by the Goths to restore their kingdom with himself as king, resolved to remain. His army was infected by dysentery, so that it was reduced from its original size of 30,000 to a size close to that of Narses' forces. In summer, Butilinus marched back to Campania and erected camp on the banks of the Volturnus, covering its exposed sides with an earthen rampart, reinforced by his numerous supply wagons. A bridge over the river was fortified by a wooden tower, heavily garrisoned by the Franks. The Byzantines, led by the old eunuch general Narses, were victorious against the combined army of Franks and Alemanni.