Historians are divided about how they summarise the campaign's result. Broadbent describes the campaign as "a close-fought affair" that was a defeat for the Allies, while Carlyon views the overall result as a stalemate. Peter Hart disagrees, arguing that the Ottoman forces "held the Allies back from their real objectives with relative ease", while Haythornthwaite calls it a "disaster for the Allies". The campaign did cause "enormous damage to ... Ottoman national resources", and at that stage of the war the Allies were in a better position to replace their losses than the Ottomans, but ultimately the Allied attempt at securing a passage through the Dardanelles proved unsuccessful. While it diverted Ottoman forces away from other areas of conflict in the Middle East, the campaign also consumed resources the Allies could have employed on the Western Front, and also resulted in heavy losses on the Allied side.

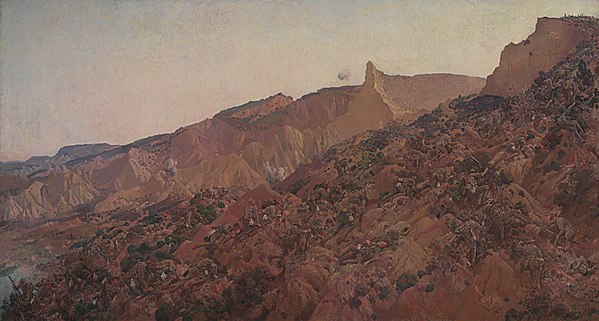

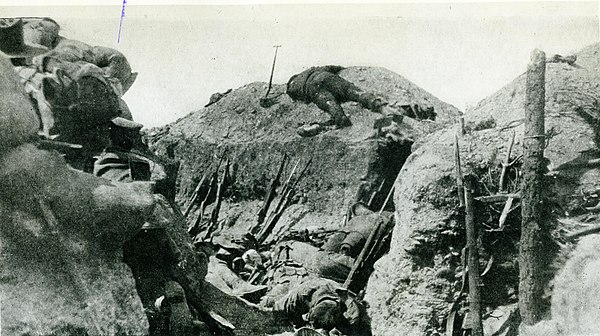

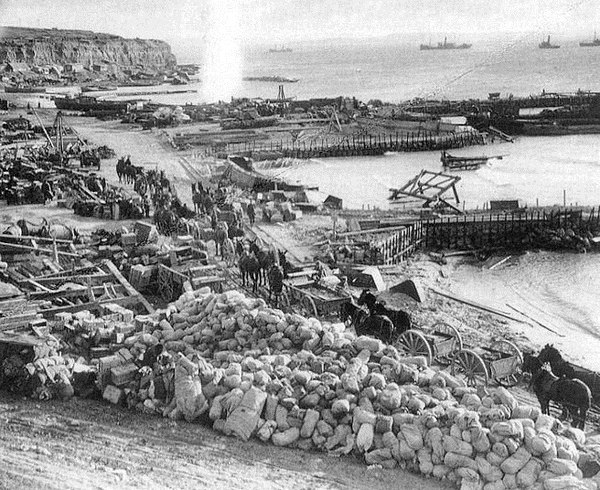

The Allied campaign was plagued by ill-defined goals, poor planning, insufficient artillery, inexperienced troops, inaccurate maps, poor intelligence, overconfidence, inadequate equipment, and logistical and tactical deficiencies at all levels. Geography also proved a significant factor. While the Allied forces possessed inaccurate maps and intelligence and proved unable to exploit the terrain to their advantage, the Ottoman commanders were able to utilise the high ground around the Allied landing beaches to position well-sited defences that limited the ability of Allied forces to penetrate inland, confining them to narrow beaches. The campaign's necessity remains the subject of debate,and the recriminations that followed were significant, highlighting the schism that had developed between military strategists who felt the Allies should focus on fighting on the Western Front and those who favoured trying to end the war by attacking Germany's "soft underbelly", its allies in the east.

British and French submarine operations in the Sea of Marmara were the one significant area of success of the Gallipoli campaign, forcing the Ottomans to abandon the sea as a transport route. Between April and December 1915, nine British and four French submarines carried out 15 patrols, sinking one battleship, one destroyer, five gunboats, 11 troop transports, 44 supply ships and 148 sailing vessels at a cost of eight Allied submarines sunk in the strait or in the Sea of Marmara. During the campaign there was always one British submarine in the Sea of Marmara, sometimes two; in October 1915, there were four Allied submarines in the region. E2 left the Sea of Marmara on 2 January 1916, the last British submarine in the region. Four E-class and five B-class submarines remained in the Mediterranean Sea following the evacuation of Helles. By this time the Ottoman navy had been all but forced to cease operations in the area, while merchant shipping had also been significantly curtailed. The official German naval historian, Admiral Eberhard von Mantey, later concluded that had the sea-lanes of communication been completely severed the Ottoman 5th Army would likely have faced catastrophe. As it was these operations were a source of significant anxiety, posing a constant threat to shipping and causing heavy losses, effectively dislocating Ottoman attempts to reinforce their forces at Gallipoli and shelling troop concentrations and railways.

The significance of the Gallipoli campaign is felt strongly in both Australia and New Zealand, despite their being only a portion of the Allied forces; the campaign is regarded in both nations as a "baptism of fire" and had been linked to their emergence as independent states. Approximately 50,000 Australians served at Gallipoli and from 16,000 to 17,000 New Zealanders. It has been argued that the campaign proved significant in the emergence of a unique Australian identity following the war, which has been closely linked to popular conceptualisations of the qualities of the soldiers that fought during the campaign, which became embodied in the notion of an "Anzac spirit".